Who looks at Lee must think of Washington;

In pain must think, and hide the thought,

So deep with grievous meaning it is fraught.

Herman Melville, “Lee in the Capitol,” April 1866.

“Be of good cheer: the flag is coming down all over, and it’s coming down because Rand Paul is right: it is inescapably a symbol of bondage and slavery, and it is inescapably a symbol of white contempt for the humanity of black people.”

Rod Dreher, “Driving Old Dixie Down,” The American Conservative, June 23, 2015

In the wake of the dark evil perpetrated by one Dylan Roof upon the members of the historic Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, we are faced with calls for the lowering of Confederate flags and the removal of Confederate monuments. That such calls emanate from the Left is nothing new. Their game has been one long demonization of the South bolstered by a Neo-Abolitionist myth that is every bit as myopic and simplistic as the other mythologies that pass for interpretations of American history. What is perhaps disconcerting to many in the South is that erstwhile allies and fellow conservatives have decided to dip into the treasury house of cheap moral vindication and even cheaper virtue. Chamber of Commerce Republicans such as Governor Nikki Haley are all about the “Benjamins.” They believe flag is bad for business so it must come down. Senator Rand Paul is a politician, and one whom I have some limited admiration for; yet he is a politician all the same and his job is to pander. Mr. Dreher, ah we shall return to Mr. Dreher in a moment. We might pause and think why these and other folk have decided to abandon the memorialization of the Confederacy? My dear reader, I suggest that we have met the enemy and it is not Haley, Paul or Dreher; it is us.

Now that I have offended you dear reader, I suggest that it well behooves us to examine the flag controversy in South Carolina back in the 1990s. The usual dichotomy came out during that debate: heritage versus hate. A compromise was eventually agreed to whereby the flag would no longer be flown from atop the state house dome, but would be transferred in a more diminutive form to a Confederate memorial on statehouse grounds. All in all this was not a terrible compromise; all parties to the debate did get something, if not everything, that they wanted. Some voices who opposed moving the flag warned that this was not a final compromise, but just a first step in removing Confederate symbols and names from public places, a type of operation memory hole. Of course these voices were correct.

The opponents of the Confederate flag do want the flag to come down everywhere. On this issue, the aforementioned Mr. Dreher and former Secretary of State Mrs. Clinton are in full agreement, odd paring though this couple may seem. This my dear reader illustrates the power of myth over the hearts and minds of Americans. The Neo-Abolitionist myth of the Civil War reduced the war to one single and solitary clause: slavery upheld by a fundamentally racist order. Like all myths there was contained in this a bit of truth. The slavery debate was certainly central to the war, but there were a host of cultural, political, and economic conflicts which were as well. Some historians have even made some noble attempts at unraveling these complexities: Avery Craven in his book The Coming of the Civil War; Anne Norton’s Alternative Americas; and Susan-Mary Grant’s, North Over South to name but a few. Much more work needs to be done, for the subject is a complex maze requiring the highest degree of skilled historical scholarship and semiotic study.

The stumbling block is that Americans, including Southerners, hate complexity. In part this is due to our pragmatic temperaments forged through frontier experiences of various sorts; in part it is also an effect of the triumph of secular puritanism in American culture. The latter is especially pernicious for it reduces all conflicts to a Manichean struggle between the forces of light and darkness. The way it works in the Neo-Abolitionist Myth is the assertion that the extension of slavery was the sole or primary cause of the war, and slavery being a horrible, racist and oppressive institution; it follows that anything associated with the old Confederacy must by nature also be horrible, racist and oppressive. Of course there are facts get in the way of this myth, but this does not stop the mythologizers. One may point out that if Southerners were so absolutely insistent on expanding slavery how was it that there were a total of 31 slaves in all the western territories in 1860? Indeed, by leaving the Union weren’t the seceding states excluding themselves from said expansion? Moreover, any southern dreams of rushing down to Cuba or Mexico would have run into a not well pleased British navy and U.S. navy. And finally, when James McPherson, a man whom the historian Gary Gallagher credited with re-introducing the “slavery is the sole cause of the war” argument into the debate, produced his book, What They Fought For, he found that the vast majority of troops north and south did not view slavery or its abolition as the causus belli; most Billy Yanks and Johnny Rebs viewed the contest as a defense of union, constitution, and hearth. The response to such findings is not to ask searching questions, but to either ignore the evidence or perhaps claim that the ordinary soldier was a dupe.

Immediately after the war two mythologies emerged to explain the war’s meaning. We might call the southern version the Lost Cause and the northern version the Union Manifest. In both versions southerners were viewed as noble and gallant opponents who had tried to thwart the march of progress, and thankfully they had been defeated. Missing form these myths were the African Americans (and I might add Native Americans), and New Left historians were right to suggest that weaving their perspective into the tapestry of the story might well help us to understand the complexities of the Civil War and its origins. Ah, but many of these folks went searching for a myth and found one in the Abolitionist worldview, a worldview that is starkly Manichean and allows for no compromise. The believers in the Neo-Abolitionist Myth are able to make a good bit of hay from the evil and disturbed actions of people like Dylan Roof.

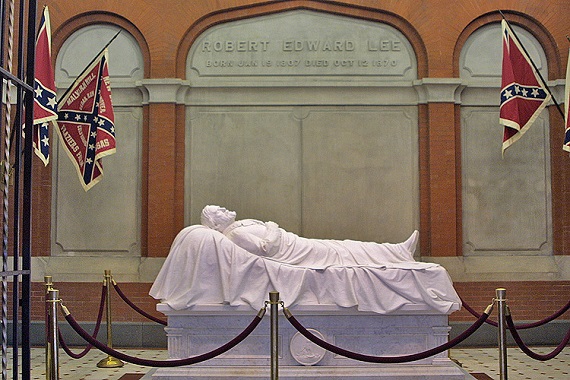

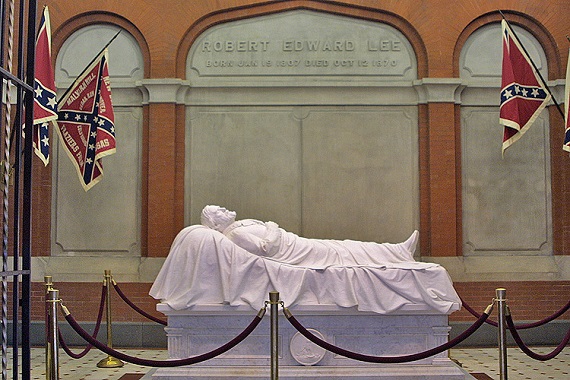

So how are we Southerners responsible for the situation in which we find ourselves? Well I believe there are at least two ways. First, the insistence that the Confederate flag and memorials only stood for “heritage, not hate” tacitly concedes the point that said flags and monuments now belong in museums. After all, most Americans associate heritage and history and other such things with museums. The second way is a bit more complex, so forgive me mythologizers and pragmatists. Southerners have rightly pointed out that the misuse of Confederate symbols by the local bigot or racist should in no way preclude their exclusion from public life. After all, the American flag, the Cross, and the Crucifix have been similarly misused. Where the Southern argument fell apart was on the point of heritage. When heritage was invoked, his opponent responded, “Yes, the heritage of slavery.” Most often the Southerner retorted that the heritage in question was a defense of home and dearth, recognition of sacrifice. The opponent would then respond again with, “No, the defense of slavery.” What was missing from the Southerner’s arsenal was the heritage of self-determination, states’ rights, and local governance. For you see dear reader, those things are, shall we say, gone with the wind. No, not when there is federal largess to be had, Duck Dynasty is on cable, and multi-national corporations must be courted. When Estonians were seceding from the Soviet Union, an action our federal government opposed, they rallied under the Confederate flag. These Estonians had a far better sense of the flag’s meaning than many of the descendants of the men who fought under that flag. What Southerners allowed over the decades was to permit their enemies and their erstwhile friends to redefine and impose meaning upon their symbols—a very dangerous concession.

I began this piece with two separate quotes. Mr. Melville, a supporter of the Union, knew the meaning of the South’s struggle, he found it embodied in Robert E. Lee and like any good American confronted with complexity he suppressed it. Mr. Dreher, who has written intelligently on a host of religious and social issues and who has positioned himself as a defender of local communities, must be warned of the path he trods. Aside from subscribing to a faulty and over simplistic, indeed even Manichean perspective on the flag, I believe him to be gravely unaware of the danger his argument contains. Allow me to edit Mr. Dreher’s words quoted above, “Be of good cheer: the cross is coming down all over, and it’s coming down because it is inescapably a symbol of anti-Semitism, bigotry, and medieval superstition, and it is inescapably a symbol of Christian contempt for the humanity of Muslims and gays.” Don’t think it would not or could not happen. Mr. Dreher has written well about the rapid secularization of the culture and the hostility towards Christians; he should know better than to dabble in the arts of the Manichean enemy. Indeed we have seen similar arguments used against Christian symbols in the past that follow Mr. Dreher’s reasoning and phrasing with respect to the Confederate flag.

It is not the Left, nor Mrs. Haley, nor Messrs. Paul or Dreher who shall bring the flag and the monuments down. We did it. We simply no longer believe in the true principles the flag embodied: self-determination, state’s rights, and local governance. We abandoned these principles and in doing so created a vacuum of meaning which our enemies exploited, and that dear reader is why the flags and monuments may well come down.