“Fatti Maschii Parole Femine”1

In July of 1861, Union troops aboard the Chesapeake Bay steamer the Mary Washington found the “privateer” Colonel Richard Thomas Zarvona hiding in one of her cabins. Aided by some sympathetic passengers, he had removed the bottom of each drawer of a dresser and had curled himself up inside of it. Zarvona’s arrest brought to an end a brief but brilliant career in the Southern forces. With a two-day expedition on the lower Chesapeake in June of that same year, he had stunned a complacent North and delivered to the South one of her earliest naval victories.

Zarvona was born Richard Thomas in St. Mary’s County, Maryland. His boyhood home, the Patuxent River plantation Mattapany, had been the site of a late 17th century battle between loyalists to Lord Baltimore and Protestant rebels who wanted “to proclaim the new king and queen.” Because it was a tradition among the wealthy families of Southern Maryland, Thomas likely attended Charlotte Hall Military Academy, the alma mater of Raphael Semmes and Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney. At sixteen Thomas entered West Point, but at the end of his first year—during which he accumulated 189 demerits—he left, and, to the relief of the Academic Board, did not return. Traveling abroad for a few years—believed to have been a soldier of fortune in the Far East and Italy—he was back home at Mattapany when Lincoln’s troops began moving into Maryland in April of 1861.

The people of St. Mary’s, receiving news that war had commenced and that the Federals had killed twelve citizens in Baltimore on April 19th, held a public meeting and resolved to raise $10,000 to purchase arms for the defense of the county, to teach Northerners “that there [could] be a ‘Lexington’ elsewhere than their soil.” But as Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts confided to Confederate spy Rose O’Neal Greenhow, the Radical Republicans “had put the iron heel upon [Maryland]” and were prepared to “crush out her boundary lines” if necessary. A few weeks after the bloodletting in Baltimore, the state now under occupation, Mattapany became a sanctuary for young men intending to fight for the South. There they waited for the chance to make their way from the Patuxent to the Potomac side of the peninsula, a team of oxen pulling the boat that they would sail over the river.

Several months before the Maryland Legislature was dispersed by the Yankees to “[break] the back-bone of the rebellion,”2 Thomas, his two brothers George and James William, and McHenry Howard, the grandson of Francis Scott Key, had all made the crossing. Thousands more from the Old Line State would follow. Because of his intractability and what was described by the war correspondent Personne as his “sky rocketry disposition,” Thomas would have made a poor infantry private. In a letter to a cousin, dated April 26, 1861, he makes the case that he “probably would be better afloat” and in command, and, to those ends, he organized and trained a group of Marylanders on the banks of the Coan River in the Northern Neck of Virginia. They would call themselves the Zouaves, their leader, with his close-cropped hair and penetrating blue eyes, considered by many to be a remarkably peculiar person.

Virginia’s governor, John Letcher, initially thought Thomas an odd individual, but he was impressed with his proposal to capture the St. Nicholas, a Union steamer that carried passengers and delivered mail to Northern gunboats in the waters off of Maryland and Virginia. Thomas’s plan involved manning the St. Nicholas with a Confederate crew and then, under false colors, to pull alongside the USS Pawnee to take possession of her also. Letcher liked the idea because that vessel was “annoying” the Confederate troops stationed at Acquia Creek, and he pledged his wholehearted support for the mission.

In June of 1861, Thomas again slipped past the Union flotilla and, at Millstone Landing in St. Mary’s County, booked passage on the Mary Washington for Baltimore. The presence of Benjamin Butler’s occupation troops had not prevented the Confederate underground in that city from thriving, and Thomas had no trouble recruiting men for his undertaking. One of them, George Watts, was eventually to serve in Pickett’s Division and to march with the “guard of honor” at the funeral of Stonewall Jackson. Destined to be the last survivor of Thomas’s band of Zouaves, Watts in 1910 was living above a Chinese laundry when a Baltimore newspaper reporter interviewed the seventy-eight-year-old veteran. Pleased to tell his story, he explained that at first he too had disliked and mistrusted Thomas, thinking that he “looked like one of [those] slick floorwalkers in a department store.” But Watts had a precipitous change of heart.

“Believe me, sir, that man had the quickest brain I ever ran across, and his eyes were just as quick. Eyes? Why, when that man looked at you it was like having an X-ray turned on you. It didn’t take us long to learn who was boss around there, so we got all our plans ready.” (“Last Survivor of a Gallant Band,” The Evening Sun, Baltimore, August 27, 1910).

On the afternoon of June 28th, in order not to attract attention, the raiders showed up a few at a time at the wharf in Baltimore to board the St. Nicholas, the Zouaves disguised as field hands for hire, their commanding officer, as Madame La Forte,3 wearing a veiled hat that covered half her face. Accompanied by her “brother”— Thomas’s Lieutenant G. W. Alexander—she was introduced by him as a milliner en route, with three trunks of merchandise and modiste trimmings, to Washington, D.C. where she was going to open a shop. Her stock in trade, unfortunately for the Federals, in reality consisted of swords, revolvers and breech-loading carbines. The trunks, miraculously, were not rifled and the arms were carried to Madame La Forte’s stateroom.

Jacob Kirwan, the captain of the St. Nicholas, later recalled that La Forte was unladylike and “looked mighty queer.” Watts agreed that she had behaved “scandalously” but praised her as an exceptionally “pretty young woman,” though some eye witnesses, however, would recollect that Madame La Forte was neither pretty nor young.

Old French women will be a terror to [the Lincoln regime]. We very much fear that that class of women, and especially those a little unhandsome…will be subjected to very rude treatment by the Lincolnites, for they will fear all of them are Southern officers in disguise. (The Daily Dispatch, Richmond, July 2, 1861)

About the time that the St. Nicholas reached Point Lookout, at the confluence of the Chesapeake and the Potomac, La Forte retired to her cabin, while on deck, Watts, completely deceived by Thomas, was beginning to think that he had never boarded the ship and to picture himself a prisoner at Fort Mc Henry.

“…I was up on deck a-wondering where it was all going to end and whether I’d be hung as a Rebel spy when someone touched me on the arm. I wheeled around like somebody had stuck a knife in me and saw Alexander. He grinned…and said: “You’re wanted in the second cabin….I hurried below decks and nearly had a fit when I found all our boys gathered around that frisky French lady. She looked at me when I came in, and, Lordy, I knew those eyes in a minute! It was the Colonel.” (“Last Survivor of Gallant Band “)

Shortly after that, the Zouaves swarmed on deck, and the astonished Captain Kirwan immediately surrendered the St. Nicholas to them. One minute the side-wheeler was steaming peacefully out of the Bay, the next, without bloodshed or drama she was in the hands of the Confederates.

Landing on the Virginia side near the mouth of the Potomac, the raiders were ready for phase two of the operation. But because the Pawnee was at the Navy Yard in Washington, they abandoned the plan to go up the river to take the gunboat and decided to head into the Chesapeake. In a matter of hours, they captured the Monticello, a brig carrying thousands of bags of Brazilian coffee; the Mary Pierce, a schooner out of Boston loaded down with ice; and the Margaret, out of Alexandria, Virginia with 270 tons of coal, a Godsend to the Zouaves because the St. Nicholas was low on fuel. The prizes, whose cargoes totaled $375,000, were taken up the Rappahannock River to Fredericksburg.

While lionizing The French Lady and “her” raiders for their coup against the North, The Daily Dispatch also tookthe opportunity to caricature Abraham Lincoln and to mock his military advisor General Winfield Scott.

“[The St. Nicholas affair] is a very beautiful addition to the number of…successful surprises by our brave Southern boys, since the struggle began. It is but the beginning, we opine, of a catalogue of daring exploits at sea that will greatly enrage the old ape, and ruffle the sweet and amiable disposition of old “Fuss and Feathers.” (July 2, 1861)

On the Fourth of July, the Zouaves and the Public Guard, on parade in Richmond, fired off twelve rounds saluting the Confederate states and the Maryland General Assembly. Since the beginning of the hostilities, Virginians had closely watched the standoff between Lincoln’s puppet Governor Thomas Hicks and the Maryland legislators, determined, Hicks was convinced, “to leap…into the vortex of Secession” and in need of “Divine ” intervention in the form of Federal coercion.

Before Thomas left Richmond, according to his wishes, he was “by legislative act” commissioned Colonel Richard Thomas Zarvona. Governor Letcher believed that the reason for his request was the notoriety of his birth name considering the false charges of piracy levelled against him by the Yankees.

Some accounts say that the colonel’s next expedition on behalf of the Confederacy was to have been the disruption of the tea trade between the North and China, others that he had proposed to take another side-wheeler tied up at Baltimore in order to harass the Federal fleet again. Whatever his mission, he made the fatal error of again booking passage on the Mary Washington. His luck having run out, he was recognized by some of the passengers, including the newly paroled Captain Kirwan. By the time the vessel had reached Fort McHenry, he was missing, however, and it would take the Yankee soldiers two hours to find him. Removed from that cabin dresser, disheveled and unsteady on his feet, he was led away to prison.

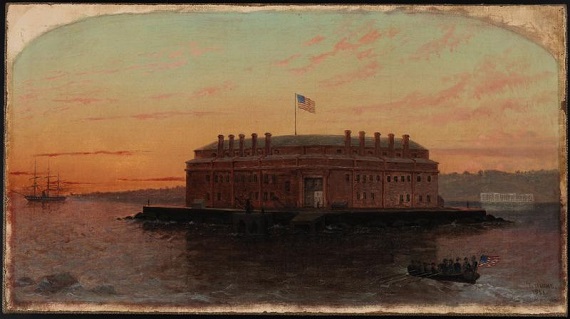

Charged as a criminal in spite of his military commission, Zarvona spent twenty one months in captivity, fifteen of those at Fort Lafayette in New York City. One night, though unable to swim, he jumped into the New York Harbor, but his improvised life preserver, a belt of empty tin cans, failed him, and he had to be rescued. Finally released on April 16, 1863, he reached Richmond three weeks later, “a wreck …unfit for military service,” according to Watts, who saw him not long after Zarvona arrived in the capital. Unconcerned about his health, hoping to take command of the newly organized United Maryland Line, he was disappointed to learn that Western Maryland’s Bradley T. Johnson had been selected. With that, he left for Europe.

After one more trip abroad, in 1872 he returned to St. Mary’s County without a penny. In his final days, he was taken in by his brother James William, dying at his residence, Deep Falls, near Chaptico, Maryland, on St. Patrick’s Day in 1875. In many respects the mercurial and eccentric Zarvona was not the equal of Admiral Semmes, Franklin Buchanan or Joseph Ridgaway (of the Hunley), Maryland’s other Confederate naval heroes, but the Southern people loved him for a time, and Governor Letcher considered him “a most …agreeable gentleman” and a patriot “insensible to fear.”

Author’s Note: This essay is dedicated to the memory of Linda Davis Reno, who passed away as she was beginning to write a book about Zarvona’s life.

- The Maryland state motto: manly deeds, womanly words.

- George B. McClellan, dispatch to Major General M.P. Banks, Sept. 12, 1861.

- Also spelled La Force in some accounts of the St. Nicholas episode.