This month marks 160 years since a relatively unrecognized, but noteworthy, battle between Union and Confederate forces in which black soldiers participated in relatively large numbers. The noteworthiness was not in terms of strategic significance, consequential results, exceptional leadership, or recognized valor.

Rather, Olustee was the battle in which a relatively recent phenomenon – black U.S. soldier regiments – probably comprised the highest percentage of any Union force during the war, approaching forty percent. Moreover, Olustee helped to convince an undecided Northern populace that recently liberated former slaves were willing and able to fight in organized units.[1]

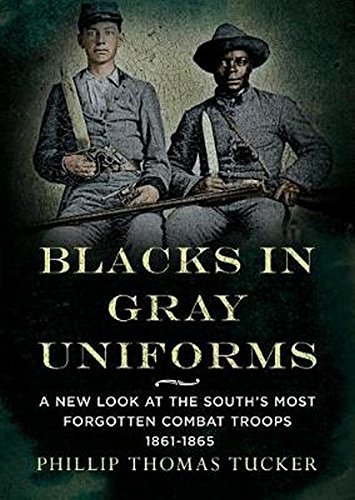

Although they fought in much smaller numbers, Southern blacks had already demonstrated this willingness and ability. One study estimates that between three and six thousand blacks – free and slave – “served in the Confederate armies in combat roles,” mostly in integrated units. One free black, John Wilson Buckner, a member of the 1st South Carolina Artillery, was “one of the forgotten black defenders of Fort Wagner.” Buckner was wounded there on July 12, 1863. Another scholar of Southern history provides a measured assessment: the choice for most Southern blacks of that day “most of the time was not between slavery and freedom, but rather just making the best of the situation which life gave them. (Like most of us, most of the time.)”[2]

In the Battle of Olustee, February 20, 1864, three black infantry regiments – the 54th Massachusetts, which earned fame at Fort Wagner (popularized in the movie Glory), plus two regiments of U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) – joined five white regiments in the Lincoln administration’s attempt to reclaim a portion of north Florida for the Union. The 54th Massachusetts was formed primarily with free blacks from throughout the north. Of the two other black regiments at Olustee, mostly free blacks from Pennsylvania comprised the 8th USCT, but the 35th USCT consisted mainly of “ex-slaves from coastal areas of Virginia and the Carolinas.” (U.S. Army policy allowed blacks to rise to the noncommissioned officer ranks, but all black units were officered by whites.)[3]

Both the 8th and 35th had been raised only months earlier and were untested in battle. Despite its enthusiasm, the 8th regiment “was still dreadfully ill-prepared for combat.” The 8th’s recently recruited soldiers had gained little experience firing their weapons despite their commanding officer’s best efforts. The 35th was somewhat better prepared, having seen limited field experience in the siege of Charleston.[4]

In early February 1864, transports carried the Union expeditionary force from Hilton Head, South Carolina, down the coast to the mouth of St. John’s River near Jacksonville, Florida, one of several Union controlled beachheads in the state. Soon after, in the words of an Army historian, the expedition began “falling apart.” The Union commander, Brig. Gen. Truman Seymour (West Point, Class of 1846, alongside Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson and George McClellan) – due either to a tendency toward rashness or perhaps still suffering trauma from a severe wound at Fort Wagner – displayed wild fluctuations in his thinking and assessment of the military and political situation. Previous reports of large numbers of Florida Unionists ready to rally to the cause proved illusory. A number of the expedition’s soldiers most familiar with the countryside remained behind, near Jacksonville. And Florida Confederates were afforded the time needed to gather a force nearly equal to the invading army of some 5,500.[5]

By the day of battle, Confederate commander Joseph Finegan had established defensive earthworks at Olustee Station, east of Lake City along the railroad line from Tallahassee to Jacksonville. Swamps and a lake (“Ocean Pond”) north of the railroad made Olustee ideal for defense, toward which he hoped to lure the approaching Union army. They never made it. Just short of Olustee, on February 20th, after initial skirmishing, seeing an advantage Brigadier General Finegan ordered his main force forward. The next few hours proved deadly.

In early afternoon, one of the two Union brigade commanders either gave an order incorrectly, or it was misunderstood, creating disorder within the 7th New Hampshire regiment. Most of the veteran regiment eventually drifted toward the rear, leaving only the untested 8th USCT in the intended position. Over the next two to three hours, the 8th suffered more than three hundred casualties out of less than six hundred men. Its commander, Col. Charles W. Fribley, was killed; his second-in-command suffered two broken legs. One lieutenant, Andrew F. Ely, wrote that his company had gone into battle with 62 men in the ranks and finished with 10 present for duty. He added, “Four times our colors went down but they were raised again for brave men were guarding them although their skins were black.”[6]

The second Union brigade, positioned on the right, fared no better, sustaining eight hundred casualties – including all three regimental commanders. As Northern losses mounted, Seymour ordered the 54th Massachusetts and 35th USCT forward – the two black regiments not already engaged. Firing quickly, by the time approaching darkness ended the fighting the 54th had expended its ammunition of forty rounds per man. As Seymour’s beaten force withdrew toward Jacksonville, in addition to the 7th Connecticut and Union cavalry, the 54th and 35th helped cover the army’s retreat. The 35th lost 230 men, including its second-in-command, Lieutenant Colonel William Reed, who died of his wounds.

The overall Union losses at Olustee were eighteen hundred, double the Confederate casualties. For the remainder of the war, the Union mounted no major military operations in Florida. Despite the outcome in this particular battle, in the end President Lincoln lauded the USCT, saying, “Without the help of the black freedmen, the war against the South could not have been won.”[7]

But one problem to remembering and learning from this battle, including the role of the black regiments at Olustee, raises its ugly head: Washington’s perverted weaponization of American history.

Simply, if West Point’s Reconciliation Plaza (a gift from West Point’s Class of 1961) and Arlington National Cemetery’s reconciliation monument can be falsely labeled as examples of the Confederacy’s “commemoration,” then certainly the Battle of Olustee – a Confederate victory – is liable to the same divisive historical treatment.

As many know, promoting reconciliation and mutual respect between North and South was the stated, long understood intent both at Arlington and West Point. In Arlington’s case, President William McKinley – a Union combat veteran and mindful of the South’s noteworthy participation in the Spanish-American War – strongly supported the monument and an associated dignified Confederate gravesite area. (The monument’s internationally acclaimed sculptor, Sir Moses Jacob Ezekiel – the first Jewish graduate of the Virginia Military Institute and a Battle of New Market veteran, called it the “New South” monument, although it is better known as the Arlington Confederate monument. Ezekiel was buried beneath it.) From the monument’s unveiling in 1914 by Woodrow Wilson, for nearly a century U.S. presidents laid a wreath at the foot of the monument on Memorial Day.[8]

But the literally unending “remit” of the divisive Naming Commission created by Congress in fiscal 2021 raises a legitimate question: are U.S. Army staff rides permitted wherever the Confederates won. (For more than a century, staff rides at select battlefields have been employed by U.S. Army and other military entities to teach and reinforce the timeless lessons of leadership, morale, tactics, and logistics for contemporary warfighters, as well as the relevance of factors such as weather and terrain.) Even if staff rides are technically allowed, what sensible up-and-coming company grade officer will volunteer to lead one at the site of any Confederate victory. In our Orwellian culture, simply naming the politically toxic victor may be misrepresented as “commemoration.”

How shameful and counterproductive to morale and combat readiness that the battle in which black regiments comprised the largest portion of the engaged Union forces and conducted themselves creditably, despite disadvantages that were no fault of their own, will likely pass unnoticed, or ignored, in Army circles. Intentional governmental conflation of the straightforward recognition of historical facts with commemoration makes it unlikely that American military members or the general public will learn about one of the early, full-fledged battles in which black regiments engaged on more or less equal terms against their adversaries.[9]

As “diversity”-crazed official Washington will learn someday, the mythical god of war doesn’t care what skin color somebody has in battle. Leadership, morale, and competence (merit) matter. That’s all. Today’s dangerously small and unprepared U.S. military – of varied skin tones – is the clear-as-crystal result of a craven political and military leadership embracing a neo-Marxist ideology currently shredding the nation’s fabric for the benefit of those whom brilliant Professor Thomas Sowell calls the “anointed,” who imagine themselves the heroic rescuers of the so-called oppressed.

Or, as an ancient inspired writer expressed, they spend their “life in malice and envy, hateful, hating one another.”[10]

***************************************

[1] Note: In the second battle in which black soldiers fought in Federal uniforms, in the action at Milliken’s Bend (Jun. 7, 1863) a Confederate brigade of 1,500 attacked 700 partially trained black recruits who defended themselves on a cotton-baled levee. Eyewitnesses stated the recruits fought hard, the main action marked by “extreme hand-to-hand violence” (pg. 115), but it was more an uncontrolled “fight” on the levee than a military “battle” for the black defenders; there was little command-and-control or intentional maneuvering on the defenders’ part; see the superb master’s thesis by Isaiah J. Tadlock, “Remembering the Battle of Milliken’s Bend,” M.A. thesis, Sam Houston State Univ., Dec. 2018.

Note: While several larger battles and campaigns in the war’s final year – such as New Market Heights (Chaffin’s Farm), Nashville, and Fort Fisher – between September 1864 and January 1865 – supported the theory that both Northern free blacks and newly freed slaves could make good soldiers, during 1863 and the 1863-64 winter, that conclusion had not yet been fairly made in the North.

[2] Phillip Thomas Tucker, Blacks in Gray Uniforms: A New Look at the South’s Most Forgotten Combat Troops, 1861-1865 (Arcadia, 2018) (reviewed by Karen Stokes at abbevilleinstitute.org); Clyde Wilson, “Black Confederates?,” Abbeville Institute blog, Jan. 6, 2016.

[3] “Thirty-fifth United States Colored Troops (First North Carolina Colored Volunteers),” battleofolustee.org; William A. Dobak, Freedom by the Sword, The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (Center of Military History: Washington, D.C., 2011), 62-71. Note: Dobak states four of the expedition’s ten infantry regiments were black, but in the battle itself black soldiers comprised three of the eight participating infantry regiments. Note: by 1864, Florida was the main supplier of beef and salt for the Confederacy’s commissary department, which the Union sought to disrupt.

[4] “Eighth United States Colored Troops,” battleofolustee.org; Dobak, Freedom by the Sword, 66.

[5] Dobak, Freedom by the Sword, 63-65, 69.

[6] Dobak, Freedom by the Sword, 65-67 [emphasis in original].

[7] Earl L. Ijames, “Black Soldiers, North and South, 1861-1865,” Abbeville Institute blog, Jan. 8, 2016.

[8] Highlighting the lack of an official designation for the monument, one work refers to “the Confederate Veterans’ area of Arlington National Cemetery”; see Kathleen Zebley Liulevicius, Rebel Salvation: Pardon and Amnesty of Confederates in Tennessee (Louisiana State University Press: Baton Rouge, 2021), 249.

[9] A staff ride study was published by the Army’s Combat Studies Institute in 2022; the chief of the staff ride team at the Army University Press reported to me, “My organization has not conducted any staff rides at Olustee and we do not have any on our schedule; e-mail, KEK to Marion, 30 Jan 2024.

[10] Titus 3:3 (New Testament).

Just as harvard plagiarists have recently admitted thousands of free blacks fought voluntarily for the Confederacy, soon it will be common knowledge most blacks in blue were forced into units raised from the newly-liberated parts of the Confederacy. Faced with jail, return to destroyed plantations or 8 dollars a month, clothing, room and board and a promise of garrison duty, they did what most would do…attempt to survive.

The most-unlikely heroes of the Confederacy were the millions of loyal slaves who took care of the wives and children of the men who went off to beat back the yankee invasion. Despite being urged to kill those left in their care, witnessing war crimes of unspeakable horror, they remained loyal…to the disgust of the invaders who thought blacks should be as mercenary and cruel as the criminal sherman and his band of psychopaths.

If it hadn’t been for black support of radical republicans who disenfranchised White Southern Males, race relations in the South would have been the envy of the world. But divide and conquer employed by proto-communists was an effective means of stripping the wealth remaining in the South, loading the South with generation’s worth of debt to repay and setting us at each other’s throats for northern gain.

Mr. Platt: I terribly enjoyed your excellent writing. Please, indulge those of us who dwell on your side, to more of your thoughts.

As much as I love the South, it is not often that I read of the “unlikely heroes of the Confederacy”, as you so accurately pointed out. What a joy!!