Because of the 1989 movie Glory, many Americans know of the battle on Morris Island in 1863 in which the black soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment fought. Very few people, however, are aware of their participation in another wartime event on this barren, sandy piece of land in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina, after Federal forces gained control of the island.

In August 1864, six hundred Confederate prisoners of war were taken out of a prison camp in Delaware and transported by ship to South Carolina. The destination for most of these men was a stockade enclosure of logs situated in front of batteries Wagner and Gregg on Morris Island. The prisoners had been sent down at the request of General John G. Foster, the Federal commander in charge of the U.S. military department in the area, for the purpose of retaliation. General Samuel Jones, the Confederate commander at Charleston, had been ordered to temporarily accept and incarcerate a large number of U.S. prisoners of war at several locations in the city. General Foster was aware that these prisoners had been brought to Charleston only out of necessity, but because some were quartered in residential parts of the city exposed to the continued Federal shelling coming from Morris Island. Foster decided to retaliate by placing a large number of Confederate prisoners directly in harm’s way.

Beginning in the first week of September 1864, soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment served as guards and wardens at the island stockade prison. During this time, after completing a tortuous journey in the sweltering hold of a paddlewheel steamboat, the captive Confederate officers disembarked at Morris Island. One of the prisoners, Captain Henry C. Dickinson, recorded their arrival in his diary:

We were met at the wharf by a full regiment of the Sons of Africa, the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts, under command of Colonel Hallowell, son of an abolition silk merchant in Philadelphia…We soon started up the eastern beach of Morris Island, guarded as closely by these negroes as if we were in Confederate lines. The gait was so rapid and we so weak that many of us utterly broke down about one and a one-half miles from the wharf, when we halted to rest, and, as it just commenced raining hard, we eagerly caught water in our hats to drink, having had none for twenty-four hours. The negroes, perceiving this, went to a spring hard by and brought us some very good water.

In a memoir, prisoner Lieutenant Henry H. Cook added these details:

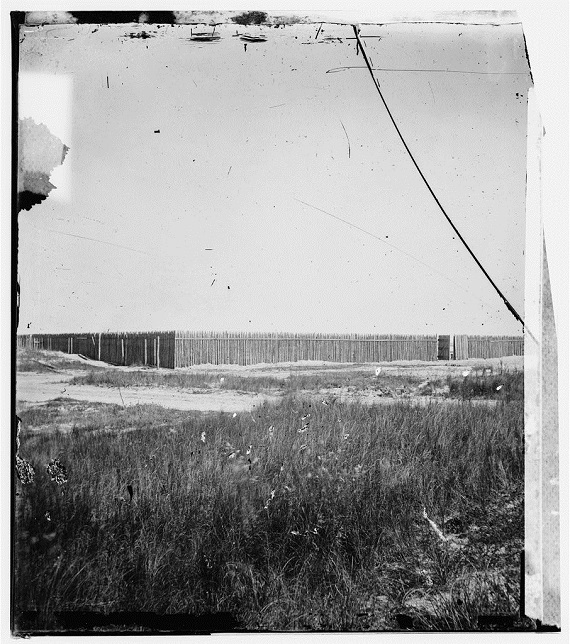

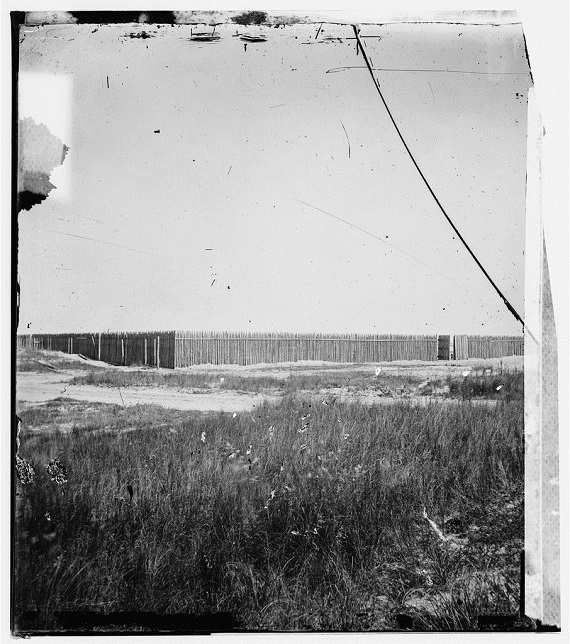

In charge of this regiment, we marched into our prison pen, situated midway between Forts Wagner and Gregg. Our prison home was a stockade made of palmetto logs driven into the sand, and was about one hundred and thirty yards square. In this were small tents and ten feet from the wall of the pen was stretched a rope, known as the “dead-line.” Outside of the pen, and near the top of the wall, was a walk for the sentinels, so situated as to enable them to overlook the prisoners. About three miles distant, and in full view, was Charleston, into which the enemy was pouring heavy shells during the night while we remained on the island. [Fort] Sumter lay a shapeless mass about twelve hundred yards to the west of us, and from it our sharpshooters kept up a constant fire upon the artillerymen in Fort Gregg. Off to the right lay Sullivan’s Island, and we could see the Confederate flag floating over [Fort] Moultrie.

In his detailed diary, Captain Dickinson recounted the artillery duels that went on between the Union fortifications on Morris Island and the surrounding Confederate forts and batteries, describing one early engagement thus:

Moultrie fired splendidly, only two or three shots falling too short; the great majority fell into Wagner. Most of our shells were from mortars and looked as if they would fall directly on us, but, whilst we held our breath in anxious expectation, its parabolic course would land it in the fort. Every good shot was applauded by us as loudly as we dared. We were but 250 yards from the spot at which these monster shells were directed, and too little powder or a slight elevation of the mortar might have killed many of us since we were so crowded together. But it was a trial of Southern against Northern gunnery…Two shells exploded over us throwing great and small pieces all about our camp. After these two last shots Moultrie fired no more at Wagner, and this was the first evidence that the Confederates knew our position between the forts…

The prisoners believed that the Confederate gunners knew the location of the stockade and directed their fire accordingly. Although some shells came close or burst overhead, affording the prisoners some hair-raising moments, none fell directly into the prison camp.

The stockade prison guards were sometimes trigger-happy, firing into the camp for what one prisoner described as trivial offenses, and wounding several men, but in general the Confederates got along well with the black sergeants who served as their wardens. Prisoner Captain George W. Nelson recalled these men, and their white commander, Colonel Edward N. Hallowell:

Our camp was laid off in streets, two rows of tents facing each other, making a street…A negro sergeant had charge of each row, calling it “his company.” These sergeants were generally kind to us, expressed their sorrow that we had so little to eat. We had a point in common with them, viz: intense hatred of their Colonel. Their hatred of him was equaled only by their fear of him. His treatment of them, for the least violation of orders, was barbarous. He would ride at them, knock and beat them over the head with his sabre, or draw his pistol and shoot at them.

The Confederate officers remained on Morris Island until the latter part of October 1864. For much of their sojourn on the island, food rations were inadequate, and many men suffered with dysentery and other complaints. Three of them died and were buried there.

When the prisoners learned that they would be leaving Morris Island, they were overjoyed, but they would soon discover that they were exchanging a bad situation for one much worse. Lt. Henry H. Cook recalled their departure:

On October 26 we were informed that we were to be taken to Fort Pulaski, at the mouth of the Savannah River. We were in the hands of Foster, and no mercy was expected or hoped for. We staggered or were hauled to the wharf and were placed upon the little schooners to be towed to Fort Pulaski. The horrors of Morris Island were not to be compared with what awaited us on the coast of Georgia…

At Union-held Fort Pulaski near Savannah, these Confederate prisoners of war would undergo an extraordinary retaliatory regime of severe rationing and other deprivations that began in late December 1864. General John G. Foster issued orders that the Fort Pulaski prisoners, and some who had been removed to Hilton Head Island, were to be put on retaliatory rations. Their rations were reduced to ten ounces of corn meal a day per man, along with a supply of onion pickles. The corn meal issued to the prisoners was several years old, rancid, and infested with insects. On January 19, Captain Henry Dickinson recorded in his diary that the rations also included a few ounces of bread. According to Colonel Abram Fulkerson, the acidic pickles were mostly rejected when it was discovered that they did more harm than good.

Many men quickly grew ill in the damp, freezing casemates of Fort Pulaski, suffering from bronchitis, dysentery, pneumonia, and scurvy, a disease of malnutrition. Seeing so much suffering around them, some compassionate Confederate officers formed a relief association, the stronger, healthier men helping those who were weaker and sick.

The suffering of the prisoners worsened, and within a month after the reduction in rations, prisoner Henry E. Handerson wrote that the sick list assumed “alarming proportions.” Another prisoner, John Ogden Murray, described the effects of the starvation diet imposed on the prisoners, writing:

Hunger drove our men to catching and eating dogs, cats, and rats…On the first day of January, 1865, the scurvy became prevalent in our prison. The doctor, whose name I cannot remember, did the best he could for us with the medicine General Foster’s order allowed him to use in practice amongst the prisoners. He would often say, “Men, the medicines allowed me are not the proper remedies for scurvy, but I can get no other for you.”

Under the policy of retaliation, the prison doctor was not allowed to give the prisoners any medicine except painkillers, principally opiates.

Some Federal medical officers who made an inspection at Pulaski in January 1865 were shocked by the condition of the prisoners. According to Henry H. Cook, “One stated that in all his experience he had never seen a place so horrible or known of men being treated with such brutality.”

In the middle of February 1865, the retaliation regime finally ended, and the Fort Pulaski prisoners began receiving much better rations. In March 1865, they were sent back to Fort Delaware, and when they arrived, many were unrecognizable to the men who had known them prior to their departure in August 1864. Lieutenant Elijah L. Cox, a Confederate prisoner who had envied the six hundred men he saw leaving Fort Delaware in 1864, was horrified at their condition, and estimated that about sixty of the officers were taken directly to the hospital upon arrival. Another Fort Delaware prisoner, Robert E. Park, described the Pulaski prisoners in his diary as “lean, emaciated persons…covered with livid spots of various sizes, occasioned by effusion of blood under the cuticle.”

Despite all the terrible hardships these six hundred Confederate officers endured, most refused to take the oath of allegiance to the United States before the war ended, an act which would have lessened their sufferings and deprivations, and afforded them a better chance of survival. For this devotion to their cause, and to each other, they became known as “The Immortal 600.”