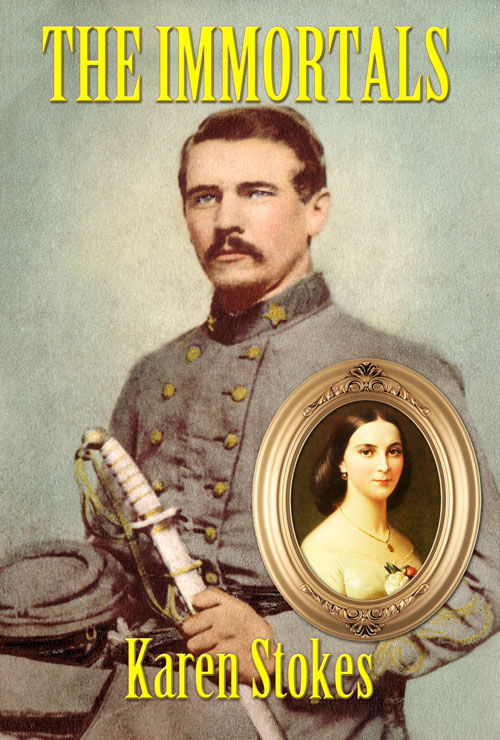

THE IMMORTALS: A STORY OF LOVE AND WAR

In 1861, as a deadly conflict looms between North and South, Charleston sits like a queen upon the waters—beautiful, proud and prosperous—and no native son loves her more than George Taylor. A successful Broad Street lawyer, Taylor has won the heart of an enchanting young woman and looks forward to a brilliant future in his city by the sea, but the turmoil of war sweeps him away from all he holds dear to defend his country. Sustained by the love of his fiancée Marguerite, he fights and survives many fierce battles, but when finally taken prisoner, he is fated to endure one of the most extraordinary ordeals ever inflicted on Confederate captives, becoming part of a group of prisoners subjected to unimaginable hardships and suffering, first in a stockade prison on Morris Island in Charleston harbor, and then at Fort Pulaski in Georgia.

On the home front, George Taylor’s family faces unexpected dangers when South Carolina is invaded by the destructive army of General Sherman in 1865. Trapped in Columbia, they experience a night of horrors as the state’s capital city is sacked and destroyed by fire. At war’s end, Taylor returns home to find his beloved Charleston in ruins, and his future with Marguerite in jeopardy.

Based on true events, The Immortals is a saga of survival and courage that lays bare some of the darkest, most tragic episodes of America’s bloodiest war.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

An old side-wheel steamship named Crescent City was waiting for them at the pier, along with two gunboats which were to act as its escort down the coast. The six hundred officers were marched on board, but instead of being allowed to remain on the upper deck as they expected, to their astonishment and dismay, they were ordered to line up at a hatchway and descend a ladder leading down into the second deck. This level, much of which was below the water line, was dark and very poorly ventilated. Here the ship, formerly a freighter, had been transformed into a prisoner transport by the construction of three tiers of shelves, or bunks, along both sides of the length of the vessel. The little light allowed in by the portholes was mostly obscured by the upper tier of bunks, and the passageway between the two sides of shelves was narrow, the space separating each tier being no more than two feet. Each bunk could accommodate three or four men at extremely close quarters.

George was one of the first to go down into the lower deck, and he immediately secured a bunk for himself and Aleck under the hatchway, where he saw that there would be some ventilation. Robert Porter and Captain Wells joined them as bunk mates.

Once the six hundred prisoners were all inside, there was little room to move around. One officer complained that they were crowded in like steers on a cattle car. A man next to him likened their situation to that of packed sardines.

A Virginia officer hazarded another comparison.

“I imagine it’s rather like being the cargo on a Yankee slaver,” he said.

“Hellfire!” a Louisianan drawled vehemently. “This is a damn slave ship!”

“I’ve seen quite a few of those,” Ned Wells piped up. “And the Yanks are indeed well practiced in that trade. Before I left New York in fifty-nine, you could see the ships built there sailing out of the harbor every month, complete with their New England sea captains, bound for Africa, as in the days of old!”

Someone wondered aloud how long their voyage south would last. After some open speculation and debate, the general consensus was a minimum of three days.

“That long!” marveled a Texan. “How shall we bear it? It’s already getting hot as Hades in here!”

“Another apt analogy for our predicament, gentlemen!” Wells observed laughingly, as they felt the ship begin to move.

Others quipped and made jokes for a while, but the initial high spirits of the men, inspired by the hope of exchange, soon faded before the harsh reality of their growing discomforts and misfortunes. The August heat was intense on deck, in the open air, but it was much worse below in the prisoners’ place of close confinement, where a number of men were forced to occupy bunks near steaming boilers and glowing furnaces.

One officer who had long experience as a sailor characterized the Crescent as the ‘most miserable ship to pitch and rock’ he had ever seen, and hour by hour, more and more of the men grew seasick. Within two days, nearly three-fourths of the prisoners were suffering with nausea, and the stench of vomit became pervasive in their quarters.

Already enfeebled by months of prison life, the captives sweltered and gasped for water, which was doled out hot from the condensers. Perspiration dripped off them constantly and saturated their clothing. Fifty at a time were allowed to go to the upper deck for a brief period of relief, but each day the prisoners stood in line for hours waiting their turn to go up to relieve themselves in the wheel house, the only facility provided for them. Sometimes the sicker men were not able to control themselves, and had to leave the line to use one end of the hold for a privy.

On her fourth day at sea, after enduring some troubles and delays off Cape Fear, the Crescent City passed by Charleston and continued down the South Carolina coast. The following morning, the ship steamed into the harbor at Port Royal many miles south of Charleston, and while it lay at anchor there, the captive officers were forced to remain in their miserable hold for several more days without any explanation. They begged for their filthy quarters to be cleaned out, but the captain of the guards refused. Once or twice the prisoners were brought water from the island, but for some reason, this supply soon ceased, and for forty long hours they suffered for water in almost intolerable heat. When it rained one afternoon, George caught some rainwater in a piece of oilcloth and shared it with his bunkmates.

During the third day at Port Royal, there was a change of guard on the ship. These new men were from two New York regiments, and though battle-hardened, they were appalled by the conditions they found on board. After a visit below deck, a soldier reporting to the new captain of guards gasped, “Foul beyond belief!” Hearing this, the commander immediately set about giving the prisoners some relief, and within hours, the ship’s hold was cleaned out. The luxuries of fresh water, coffee, and bread were provided, and the men were permitted some time on the upper deck. Some invalid and extremely sick prisoners, forty in number, were put on another boat and taken to nearby Beaufort.

On August 29th, the Crescent City set out to sea again with her cargo of prisoners, and two days later the ship arrived off Charleston harbor. Here the prisoners saw waters full of Federal monitors, gun boats, and blockaders, and witnessed repeated explosions of shells hurled from blazing artillery at the batteries and forts. The steamship proceeded a little way into the harbor and anchored near Battery Gregg, but almost another week passed before the Confederate officers were told that they would soon disembark at Morris Island, where a stockade prison awaited them. They believed this place to be merely a temporary holding pen until the exchange took place; most did not expect to be there longer than a few days–until they were informed otherwise. As the steamer approached Morris Island, a large, barren isle of sand, it was announced to the prisoners that there would be no exchange. Instead, they were told that they would be held in this place for an indefinite period, under the fire of their own guns.

Though the sky was overcast that morning, the prisoners emerged from the darkness of the ship’s hold blinking, squinting, and shading their eyes in the daylight. They had not yet received any breakfast or water, and smacked and licked their parched lips with what little moisture that was left in their mouths. They moved slowly down the gangplank and were then marched from the wharf to the island, where they felt terra firma under their feet for the first time in nearly three weeks. Many heads immediately turned to look off in the direction of Fort Sumter, now reduced to little more than a shapeless mass of rubble after repeated bombardments, but still manned and active against the enemy.

When George and his fellow officers were assembled on the beach in the presence of their guards, he was struck with an extraordinary and strange spectacle as he looked about him. Five hundred and sixty Southern soldiers—pallid, hungry, some of them ill and tottering, and clad in all kinds and faded colors of garb, military and otherwise—faced orderly lines of black men dressed in identical, neat blue uniforms, all looking quite fit and well-fed.

To heighten the contrast, the skin of the prisoners had been bleached to the palest shade of white possible from their extended journey in darkness. What few worldly goods they possessed were wrapped in the remains of old quilts or other fabrics, or hung from their sagging shoulders in worn cotton haversacks.

At Fort Delaware George had used some of the money sent to him to replace his disintegrating uniform, and refusing anything issued to Federal soldiers, he had finally managed to put together an odd combination of old civilian clothes. After being soaked in perspiration for weeks, they were filthy, and torn in places. The seam of one of his trouser legs had split to a point above his knee, and the cloth flapped open in the sea breezes to reveal a muscular, ghastly white calf thinly covered with dark hair, the scar of his old Kinston wound plainly visible. As he stood on the hard sand beach, the surf in his ears, the wind whisking his hair in every direction, it occurred to him that he must look very much like Robinson Crusoe. All he imagined that he lacked was a full beard; he had the beginnings of one now, and his thick brown hair had grown longer, hanging over his eyes and ears in a tangled, shaggy mess.

The ship’s guards were ordered to take away from the prisoners the blankets they had been issued earlier, and while this was going on, the black regiment went into a short demonstration of the manual, or rifle drill, following shouted orders from their white officers. Few things stirred the indignation of Confederate soldiers so much as the sight of black men in blue uniforms, since they assumed them to be fellow Southerners and therefore traitors to the cause–but now, in their situation as prisoners of war, they looked on these men with other feelings, mainly curiosity and apprehension. Some of the officers smirked derisively, amused, having never before seen black men deport themselves as soldiers in such a formal way, while those officers who had, earlier in the war, fought against the men of this regiment, in this very place, gazed at them warily, wondering if they were vindictive sorts. Other officers studied them with interest, and had to admit that they certainly looked soldierly and performed the drill skillfully.

Flanked on both sides by companies of enemy soldiers, the captive men began a march of nearly three miles along the beach toward the stockade pen. Some were so weakened and sick from the sea voyage that they stumbled and fell numerous times on the way, and the other prisoners raised them up and helped them as much as they could. After they had covered about half the distance to the stockade, it began to rain, and the thirsty men immediately set about catching water in their hands and hats, sucking in every drop for dear life. Seeing that a number of the prisoners were about to collapse from thirst, a few of the black soldiers brought them water from a spring not far away. For this kindness, they were reprimanded by their officers.

Soon the prisoners were within sight of a stockade composed of upright pine poles about twelve feet high, with sharpened tops. Passing into the stockade through a gate, they walked into an enclosure covering an area of an acre and a half, where tents housing four men each were set up in eight rows. Wishing to stay together, George, Aleck, Robert, and Captain Wells quickly claimed a tent for themselves, and Captain Levy became one of the occupants of the tent next to theirs.

After a brief rain ended, George and his three companions, joined by Captain Levy, sat in front of their tent taking in their new situation, observing first along each of the four log walls a “dead line” of coarse rope strung about twenty feet in. Atop the stockade walls, they could see parapets where armed black soldiers were stationed as sentries.

George wondered if the guards here would be as quick to pull the trigger on prisoners as the ones at Fort Delaware.

“Let’s hope not,” said Captain Levy, as he waved away a mosquito buzzing near his face, while Captain Wells slapped at a gnat biting into his bare arm, cursing such pestilences.

As their conversation continued, it was frequently interrupted or drowned out by the firing of the Yankee cannons in Fort Wagner, a fortification located only about one hundred and fifty yards behind the stockade prison.

“There will surely be some return fire soon,” Robert ventured reluctantly. “Then things will get really interesting here.”

“Yes, very interesting,” Levy agreed, “to be fired upon by our own guns.”

“Who would have believed it,” Aleck marveled, shaking his head, “that we would be placed in such a situation!”

“It almost happened before, you know,” said Captain Wells, “with the fifty officers who were sent down here in June.”

“I heard those rumors,” Aleck replied, “but I could hardly believe they were true.”

“It was no rumor,” said Wells. “Those men were lucky, and got exchanged. We, however, have jumped from the proverbial frying pan into the fire—artillery fire!”

His joke elicited some nervous laughter, until the booming guns of Fort Wagner suddenly put an end to it. Soberer reflections followed, as the five men speculated how long they might be kept in this place.

In the afternoon, all the prisoners were called to form ranks in one of the “streets” between the rows of tents, to be instructed on the rules of the prison camp. Afterwards, the men went back to their tents, and on the way, overhearing some interesting conversations, George made inquiries among a few officers who had gleaned some information from the ship’s guards, and from newspapers, about the series of events and circumstances that had brought them to Morris Island. What they told him made him feel much less hopeful that any exchange was in their future.

General Jones, the Confederate commander at Charleston, had been forced to temporarily accept and incarcerate a large number of captive U.S. officers at several locations in the city. General Foster, the Union commander, knew that these prisoners had been brought to Charleston only out of necessity, but because they were quartered in parts of the city exposed to the continued Federal shelling, he decided to retaliate by placing a large number of Confederate prisoners directly in harm’s way. After learning all these facts, George passed the information on to his friends, all of whom received it with the same dismay. Captain Wells angrily declared that he had given up all hope of exchange.

Just two days after George and his fellow prisoners arrived at Morris Island, an intense artillery duel began between the Federal batteries and Fort Moultrie, lasting from dusk until ten o’clock. The firing began from Fort Wagner, and in due time return fire came in from across the harbor. Startled and alarmed, the prisoners could only watch helplessly as the shells flew overhead, and hope that none of them fell into their area. A few of the shells burst from the guns at Wagner prematurely, scattering fragments throughout the prison pen, but fortunately, no injuries resulted.

After this episode, the shelling from both sides continued, in varying degrees of intensity, nearly every day. Even though the prison stockade had been strategically placed directly in front of the Federal batteries, it soon became apparent that the presence of the prisoners did nothing to shield those installations from Confederate fire. The gunners in the Confederate harbor forts and batteries seemed to know the exact location of the prisoners, and directed their artillery fire accordingly. A few guards were killed or wounded by the shelling, but none of the prisoners were done much harm. There was, however, an occasional close call, and it was enough to make some of the defenseless captives nervous.

The imprisoned officers were assigned to daily menial tasks necessary for the maintenance and cleanliness of the stockade. When these were finished they found other ways to pass the long, monotonous hours of their captivity, and to distract their minds from the constant threat of exploding shells in their midst. They played cards or chess, wrote in diaries, washed their clothes, read books and Bibles, chatted, and hatched a few futile schemes of escape.

Rules governing the inmates were very strict, and any violation, such as crossing the dead line, could bring on gunfire from the sentries on the parapets. As the officers settled in to their sorry life in the stockade, routines were established, and relationships, not always pleasant, developed between the prisoners and their captors. Though the guards were sometimes abusive and trigger happy, the Confederates were soon on friendly terms with the black sergeants who served as their wardens. Many of these soldiers had at least one thing in common with the Confederates–a healthy hatred of the commander, Colonel Hallowell, who treated his colored troops only a little less harshly than the prisoners.

During the first few weeks of their confinement in the stockade, Hallowell withheld the prisoners’ mail, limited their drinking water, and fed them on a meager daily diet of a few crackers, a half pint of watery soup or rice, and two ounces of salt beef, often spoiled. During the fourth week of their captivity on the island, the prisoners’ rations were reduced even further. Barely subsisting on such fare, many of the men began to grow weak and sick with intestinal disorders. When they first arrived on Morris Island, they had feared for their lives because of their placement as human shields, but as time wore on, they grew more concerned that they might slowly perish of malnutrition.

A few of the black wardens risked punishment to do kindnesses to the prisoners, sometimes doling out double or triple portions of food to those who seemed to need it the most, or now and then even smuggling in a better quality of eatables for them. Some of the wardens seemed ashamed of the paltry rations they gave to those in their charge. One day, when one of the officers complained of the poor food, a black sergeant agreed with him that they were hardly fit for a dog to eat.

“But it’s all these Yankees are going to give you,” he added contemptuously.

Aleck and Robert found particular favor in the eyes of one of the sergeants, an older man in the regiment who said he had been a barber in Boston. He was a religious individual, and when he found out that Aleck and Robert were seminarians, he brought them double rations every day, clear spring water, and portions of vegetables and bread whenever he could. Thanks to him, the two young clergymen fared reasonably well on Morris Island, though both steadily grew thinner, like every other prisoner. George’s once muscular physique had certainly become leaner. His face had new concavities, and on different parts of his body, he began to notice the protuberances of bones he had never seen before.

In the second week of September, the prisoners were given the demoralizing news that General Sherman had captured and burned the city of Atlanta. The following week, one of the officers, a lieutenant from Tennessee, succumbed to malnutrition and dysentery. A few days later, another officer died of the same causes, and about two weeks after that, a third prisoner was dead due to pneumonia and complications of wounds that had never properly healed. It was not until mid-October that the prisoners were allowed to receive mail and packages, and given access to the post sutler, from whom they could buy food and tobacco. Rations also improved about this time, after Hallowell’s cruelties were reported to a superior officer.

As soon as the mail resumed, George received a letter from Marguerite dated the tenth of September. He knew she must have written others since this one, but did not know if they had been returned or destroyed. Believing that George was to be exchanged, she had written to him in a hopeful, even cheerful mode. Some of her old friends had come to Greenville, and she wrote of their work and play together. Marguerite related that while she and her friends busied themselves sewing and knitting for the Soldiers’ Aid Society, they reminisced about their girlhood together, and one afternoon, treated themselves to a picnic in the countryside. They had gone out on horseback, and after their meal, enjoyed themselves in races up and down the hills, during which Marguerite bounced wildly in the saddle and laughed so hard that tears came into her eyes. It made George smile to think of her having such fun, and finding such companionship.

That night he dreamed of Marguerite. He often wished that he had control over his dreams–too many of them turned out to be troubling, or nightmares of the worst kind, no matter how diligently he tried to think of only pleasant and comforting things before he fell asleep—but this particular dream, unlike most others, took him where his fondest desires wished to go. In it he saw himself in a beautiful and well-kept garden, a place of gracefully arranged greenery and flowers. Dressed in white like a bride, Marguerite was there, seated on the ground in a grassy area. She was reading a book of poetry, and looked up and held out her hand to George as he approached. He went to his knees beside her, tossed away the book, and gently pushed her back and fell with her to the soft, sweet-smelling grass. Face to face, their faces very close, she looked up at him and smiled, and he pressed a kiss to her lips.

“My wife,” he whispered.

“My darling,” she replied.

But his bliss was rudely and abruptly dispelled by a jarring noise in his ears from the real world. A loud voice was shouting just outside his tent. As usual at dawn, one of the sergeants was bellowing out orders to the prisoners.

What a dream he had interrupted! George sat up angrily and stumbled out of the tent.

“From paradise to purgatory,” he was thinking, shambling into place for the morning’s roll call.

As this first tedious routine of the day dragged on, interrupted only by the cries of sea birds, George looked up at the dawn sky. It was one of those soft, pastel skies more often seen in summer, a faint pinkish hue below giving way to a pale clear azure blue above, while the far western heavens were still a fading grey. A canopy of clouds overhead were formed in undulating rows that resembled the pattern left on a beach by the receding tide. Almost unconsciously, he had fallen into the habit of surveying the eastern sky each morning, to note its unique daily appearance, but he was really renewing an old habit, from a time before the war, when he almost always began the day with a walk along the Battery. Each morning, he recalled, there was a new exhibit to admire, always different from the last, and always beautiful in some way in its changing palette. On Morris Island, George could never see the horizon, which was obscured by the stockade wall, but he could see what was above it, and for a few brief moments, the beautiful and peaceful sight overhead offered a morsel of consolation in the face of a ruder sort of dawning–the roll call—marking the beginning of another miserable, deadening day of captivity.

That morning and afternoon passed in much the same way as every other day on the island passed, and just after sunset, the rumblings of artillery fire began again as usual. Most of the shelling took place after dark. George could never sleep while these noisy operations were going on, and, having nothing better to do, he would often sit in the door of his tent and watch the sky. There was a kind of grandeur in the spectacle after all, distressing as it was to him. At night, the firing guns resembled flashes of lightning, sometimes illuminating the whole sky, and the fuses of their projectiles made fiery streaks across the heavens like meteors.

It was not so pleasant when the shells thrown in by the harbor batteries and forts burst just beyond the prison stockade. With each boom from the Confederate installations in the distance, George would cringe and await the shell that was surely on its way, hoping it would not fall short but find its target at Fort Wagner, or at nearby Battery Gregg.

He remembered standing on the sea wall of Charleston before the war and gazing out on the harbor, where the mighty Fort Sumter appeared to be little more than a speck, not much larger than a hand’s breadth in the distance. Yet from an even remoter distance, from the vicinity of Morris Island, shells were being thrown into the city by new, powerful artillery pieces. That these destructive projectiles could travel through the air a distance of five miles–five miles! he marveled–was a feat unheard of before this war. While watching from Sullivan’s Island one evening, he remembered how his jaw had dropped in astonishment the first time he observed a shell hurtling across the harbor waters towards Charleston. Now, even after witnessing the same sight hundreds of times, he still looked on with amazement–as well as disbelief, sorrow, and indignation–unable to comprehend what military purpose it served to batter houses and shops and churches.

“My city,” he whispered mournfully, hearing the dull, heavy explosion of a shell that had found its faraway target, “my beautiful city.”

Order a copy of The Immortals to read more.