By mid- January 1865, General Sherman’s campaign in South Carolina had begun in earnest. Some of his forces began moving through the parishes of Beaufort District at this time, and one of their first targets was the village of Hardeeville, where troops of the 20th Corps arrived on January 17th. During their days there, they burned down or tore apart the town, taking down many of the buildings to make shelters for themselves. Hardeeville’s Baptist church was also dismantled. As the church fell to pieces, the soldiers taunted the townspeople: “There goes your damned old gospel shop!”

Before the invasion, General Sherman had been explicit about his intentions to ravage the state, and his troops showed themselves eager to carry out those intentions. In a letter to General Henry Halleck, Sherman wrote, “The truth is the whole army is burning with an insatiable desire to wreak vengeance upon South Carolina.” David P. Conyngham, a New York newspaper correspondent traveling with Sherman’s army, made a similar observation:

There can be no denial of the assertion that the feeling among the troops was one of extreme bitterness towards the people of the State of South Carolina. It was freely expressed as the column hurried over the bridge at Sister’s Ferry, eager to commence the punishment of “original secessionists.” Threatening words were heard from soldiers who prided themselves on “conservatism in house-burning” while in Georgia, and officers openly confessed their fears that the coming campaign would be a wicked one. Just or unjust as this feeling was towards the country people of South Carolina, it was universal.

Conyngham gave a specific example of the soldiers’ vindictive attitude, describing the case of a plantation house they set on fire and plundered early in the march into South Carolina:

The soldiers were rushing off on every side with their pillage. An old lady and her two grandchildren were in the yard alarmed and helpless! The flames and smoke were shooting through the windows. The old lady rushed from one to another beseeching them at least to save her furniture. They only enjoyed the whole thing, including her distress. (emphasis added)

Meanwhile in January, other Federal forces operating in concert with Sherman’s army came up out of the Beaufort area, moving north along the coast toward Charleston. One of the units in this force was the 56th New York Infantry Regiment. Dr. Henry Orlando Marcy, a surgeon in a brigade under the command of Colonel Charles Van Wyck, made observations in his diary about the operations of his unit in Beaufort District, noting on January 19th that the 56th New York Infantry Regiment burned much of the village of Gillisonville, including the jail, a hotel, several dwelling houses, and a courthouse full of irreplaceable public records. The nearby village of Grahamville was also destroyed at this time. Captain Norman Crossman of the 56th New York also noted the destruction of Gillisonville in his diary on January 19th.

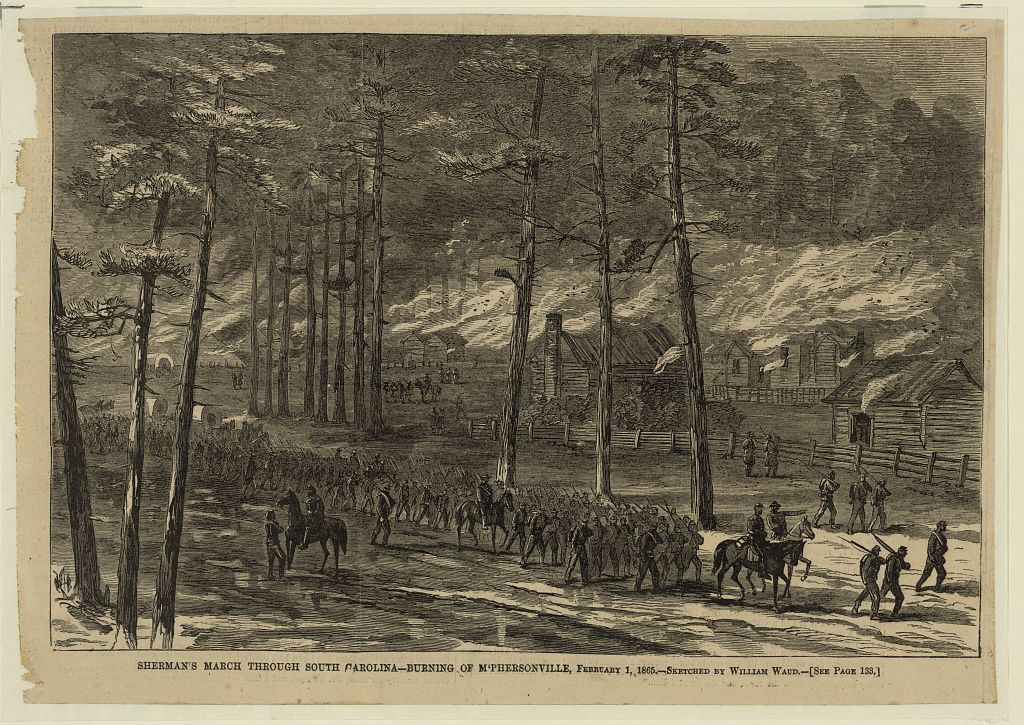

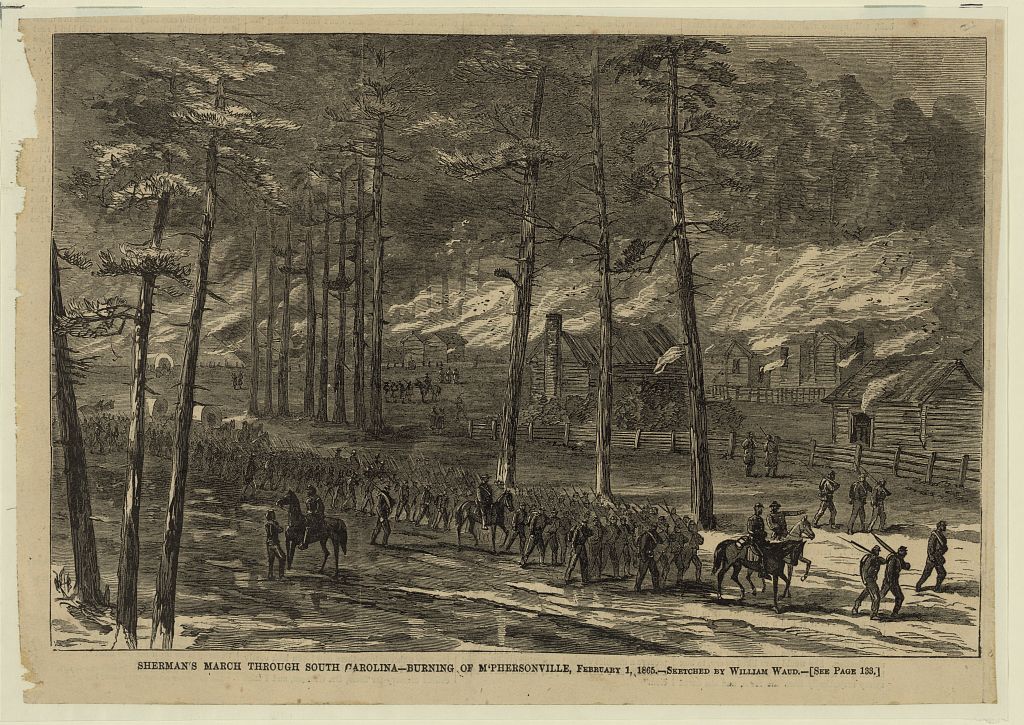

On January 14th, Sherman’s forces put the torch to the Episcopal church building in Prince William Parish, commonly known as Sheldon Church. Its massive walls still remain today as beautiful ruins, but the interior of the church was burned by the Federals, just as it was burned by the British during the American Revolution. On January 31st, General Logan’s 15th Corps torched the village of McPhersonville, effectively wiping it off the map. Private John Rath, one of Logan’s soldiers, noted in his diary how “the boys” set fire to nearly every house in the village.

Sherman’s armies met with little in the way of military opposition from the relatively small number of Confederate forces in the state, who were compelled to withdraw and burn bridges behind them as a force of over 60,000 Union troops relentlessly moved inland.

The month of January was just a taste of things to come for thousands of South Carolina civilians.