The history of political parties in America is as old as the United States itself and while the seeds of England’s Whig and Tory Parties goes back to 1679, those in America even predated the rise of most such factions in Europe by several decades. However, for half a century many of America’s founding fathers, particularly those in the South, maintained a deep distrust of such organizations, as expressed in 1822 by President James Monroe who considered “ their existence as a curse of the country.”

The initial political party in America was the Federalist, founded in 1789 by a group of political leaders from the Northeast led by Alexander Hamilton, John Adams and John Jay. The Democratic-Republican Party was begun three years later by three future presidents from Virginia, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and James Monroe. Hamilton and his followers were in favor of a strong national government, centralized authority and a federal bank. Jefferson and his party, on the other hand, opposed such concepts and favored less central control, a more agrarian society and a greater degree of sovereignty left in the hands of the states.

One of Hamilton’s first actions as Treasury secretary was the imposition of a federal tax. Acting on the section of Article One in the Constitution that allowed Congress to “ lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises,” he brought about passage of the Tariff of 1789, a tax imposed on foreign goods coming into the United States. This was to not only raise funds for running the federal government, but to protect and subsidize American industries which were mainly located in the Northeast. Hamilton’s tax became an important factor in the various disputes that arose between the North and South over the next seven decades which ultimately led to secession and its ensuing war.

By the year 1828, opposing factions within the Democratic-Republican Party caused a split in which a group led by Andrew Jackson and those who favored Jefferson’s principles formed the Democratic Party. Those who had moved away from Jeffersonian ideals joined with the now defunct Federalists to form the National Republican Party under John Quincy Adams. That party lasted only until 1834 when Senators Henry Clay of Kentucky and Daniel Webster of Massachusetts formed the Whig Party which favored an even stronger federal government and greater economic nationalism.

Just prior to this period, the expansion of slavery in America had started to become a serious political issue that led to the Missouri Compromise of 1820. That action allowed Missouri to be admitted to the Union as a slave state and Maine as a free state, as well as prohibiting slavery in any state or territory in the vast upper Mid-West area that was part of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. The controversy continued, however, and in 1854, those opposed to slavery’s expansion and were in favor of a more progressive economy and social structure joined with Free Soilers and members of the fading Whig Party to create the present Republican Party.

The new party quickly became the leading opponent of the then dominant and more conservative Democratic Party and within two years the Republicans ran a presidential candidate, former California senator John Frémont. In the election of 1856, the winning Democrat, James Buchanan, carried every Southern state, as well as Illinois, Indiana, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and even Frémont’s home state of California. All of the nation’s political issues finally collided four years later with the narrow victory of Republican Abraham Lincoln over three badly divided Democratic candidates.

The end of Lincoln’s war against secession saw not only the virtual demise of the Democratic Party in the South, but a loss of power in North as well. In the election of 1868, the first after the War, Republican candidate General Ulysses Grant swept to victory over former New York governor Horatio Seymour with an electoral vote of two hundred fourteen to eighty. Seymour only managed to carry two of the former Confederate states, Georgia and Louisiana, and three border states, Delaware, Kentucky and Maryland. Grant won again four years later, with Democrat Horace Greeley, the New York newspaper publisher, winning just three former Confederate states, Georgia, Tennessee and Texas.

As the Reconstruction era was drawing to a close, the election of 1876 saw a major reversal in the fortunes of the South’s Democratic Party. The party’s candidate, Samuel Tilden, lost to Republican Rutherford Hayes by only one hotly contested electoral vote. Tilden also lost only three of the former states of the Confederacy, Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina, but all by razor-thin margins. That election saw the rebirth of the “solid South” for the Democrats, and they were to carry every former Confederate state for the next fifty years.

Some disruption of this took place in 1928 when Alfred Smith, the four-term governor of New York and the first Catholic to run for president, was the Democratic candidate. The election soon developed into a vicious, anti-Catholic campaign, with the still-strong Northern elements of the Ku Klux Klan having an effect on voters. As a result, Republican Herbert Hoover overwhelmed Smith by four hundred forty-four to eighty-seven electoral votes, carrying every state except Massachusetts and six in the deep South that still remained loyal to the Democratic Party.

The situation was reversed four years later when Democrat Franklin Roosevelt defeated Hoover by carrying forty-two of the then forty-eight states, including every state in the South. The South again remained solidly Democratic until 1948 when many Democrats in the region became disillusioned by the sharply leftward trend in the party’s positions and its efforts to overturn many laws that existed in the South, particularly those related to segregated facilities. Rebelling against what they considered to be a sell-out of states rights, many of the Southern delegates left the 1948 Democratic Presidential Convention in Philadelphia.

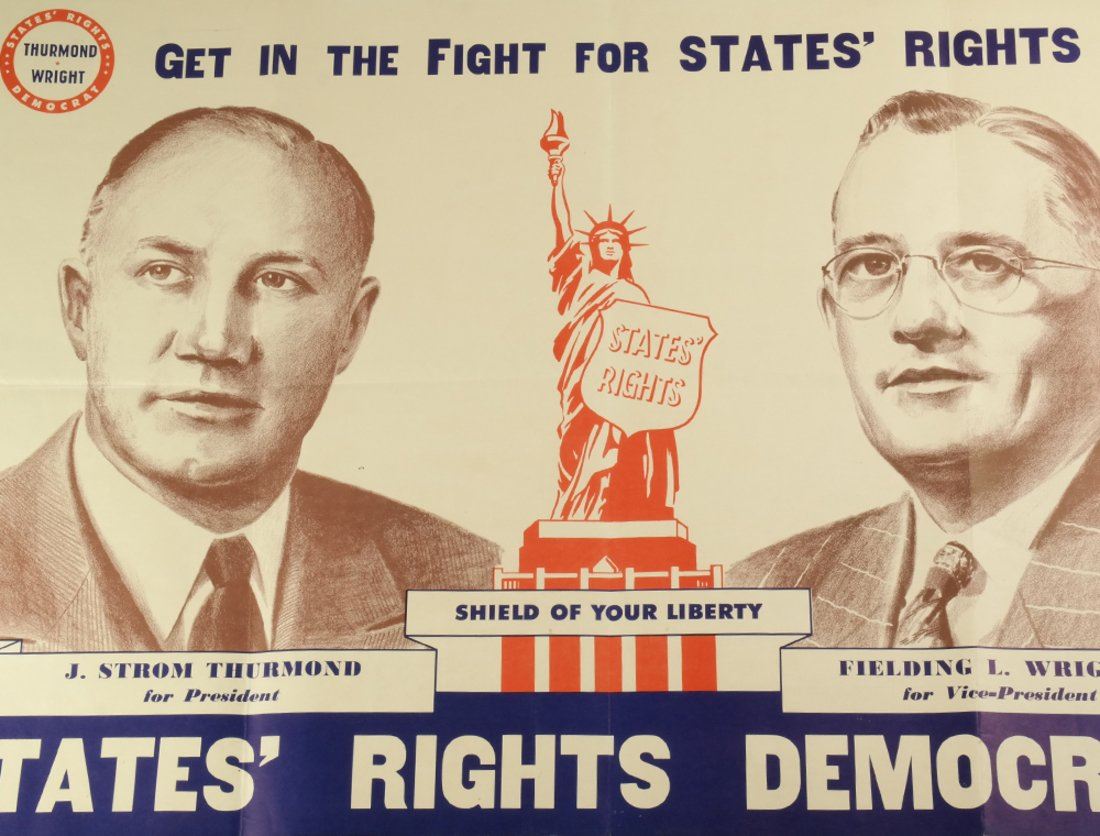

The Southern delegates then held their own convention in Birmingham, Alabama, and formed the States Rights Democratic Party, better known as the “Dixiecrats,” with Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina as their candidate. Thurmond ran against Democrat Harry Truman, Republican Thomas Dewey and Progressive Party candidate Henry Wallace who was threatening to split the Democratic vote in the North. Even though Thurmond carried four of the former Confederate states, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina by large majorities, Truman won the other seven Southern states and went on to an unexpected victory.

While the states that voted for Thurmond returned to the Democratic fold in 1952, the landslide victory of Republican Dwight Eisenhower that year also included the former Confederate states of Florida, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia. The pattern remained the same four years later, with Louisiana being added to the Republican column. In 1960, however, Senator John Kennedy’s close victory over Vice-President Richard Nixon saw the South, except for Florida, Tennessee and Virginia, again voting solidly Democratic.

The political picture of a slightly less “solid South” was then redrawn completely in 1964 when President Lyndon Johnson ran against conservative Republican Barry Goldwater . . . but the contest was not the one that had been initially envisioned by either party. When Goldwater and Kennedy were in the Senate in the 1950s, they had been on very good terms despite their ideological differences. Prior to his nomination in 1964, Goldwater and then President Kennedy had agreed that if they faced each other that year there would be no personal attacks or negative campaigning. Instead, they had planned a series of Lincoln/Douglas-type debates on both the problems facing the nation and the liberal versus conservative means of resolving them. All this ended with the president’s assassination a year prior to the election.

The Republican primary campaign had been a particularly ugly one, with charges of extremism and racism being hurled at Goldwater by his liberal Republican opponents. The racist label grew from Goldwater’s lone vote that year against certain provisions in the Civil Rights Act which he felt were unconstitutional, and were later proven to be so. The charge was specious, however, as Goldwater was a staunch supporter of racial equality and had long been a member of both the NAACP and the Urban League. He also had a record of promoting desegregation, having integrated not only his own Phoenix department store in 1930 but also that city’s school system a year before Brown v. Board of Education and the Arizona Air National Guard two years before segregation ended in the U. S. military.

As to the rather amorphous term “extremist,” while both his Republican and Democratic opponents constantly used the word to portray Goldwater as a menace to both the country and the world, he refused to shrink from the label. Even in his acceptance speech in California that July, Goldwater paraphrased Cicero by saying that “ extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice . . . moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.”

The charge became more visceral just a month before the election with the infamous “daisy” television ad that provided a mortal blow to the Goldwater campaign. In it, a little girl was seen picking the petals off of a daisy while a voice began a countdown followed by a nuclear blast. Johnson’s voice was then heard saying. “These are the stakes. To make a world in which all of God’s children can live, or to go into the dark. We must either love each other or we must die.” A voice then urged people to vote for President Johnson.

In the election, while Johnson won sixty-one per cent of the popular vote and all but six of the fifty states, in the South Goldwater was victorious in Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina by wide margins, as well as coming close in five other former Confederate states. Even in Johnson’s home state of Texas, Goldwater received almost forty per cent of the vote. Four years later, while Texas stayed Democratic and five of the deep South states voted for the third-party candidate, Governor George Wallace of Alabama, the rest of the South voted Republican. Except for Jimmie Carter’s Democratic sweep in 1976 following the Nixon Watergate scandal, the Republican hold on the South has remained fairly solid for over half a century.

For only a few brief periods in America’s political history has the Jeffersonian dream of a republic composed of a confederation of sovereign states working in concert with a limited federal government ever had any real chance of coming to pass. Likewise, there seems to be little hope of any real contest between conservative and liberal principles ever taking place, let alone any reversal of the ever expanding federal government. Jefferson’s conservative principles of government are virtually a lost cause among Democrats today, even in the South, and the South’s Republicans have also lost the conservative compass they found in 1964 with Barry Goldwater. For the past thirty years, the G. O. P. has drifted further to the left and has accepted the Democratic Party’s welfare mind-set and the endless entitlements which were started during Roosevelt’s New Deal over eighty years ago. Policies that have now created a national debt one third greater than the country’s total gross national product.

While many today complain of high taxes, soaring prices and the central government’s constant intrusion into their daily lives, far too few would actually be willing to forego the benefits those tax dollars now provide or eliminate the agencies through which such munificence flows. Furthermore, the ever-widening divisiveness in America’s political parties, like much of the same throughout the nation itself, now seems to be creating a lost cause in the eyes of many who sadly see their country lapsing into, as with the Roman Empire before its fall, a time of bread and circuses.

The States sold us out when they allowed the IRS to exist…all part of one huge “democracy” which was never the intention of the founding Fathers. First we were handed the IRS, income tax and Federal Reserve…then we lost the States selecting Senators…then we got 2 wolves and one sheep voting to decide what to eat for dinner.

What’ worse? To be a slave in the United States or to be a slave to the Germans because our 50 squabbling States couldn’t defeat the Germans?

You do realize the income tax was declared unconstitutional and that “legal issue” was settled in Pollock vs Farmers?

It’s all about the money…including the War Between the States.