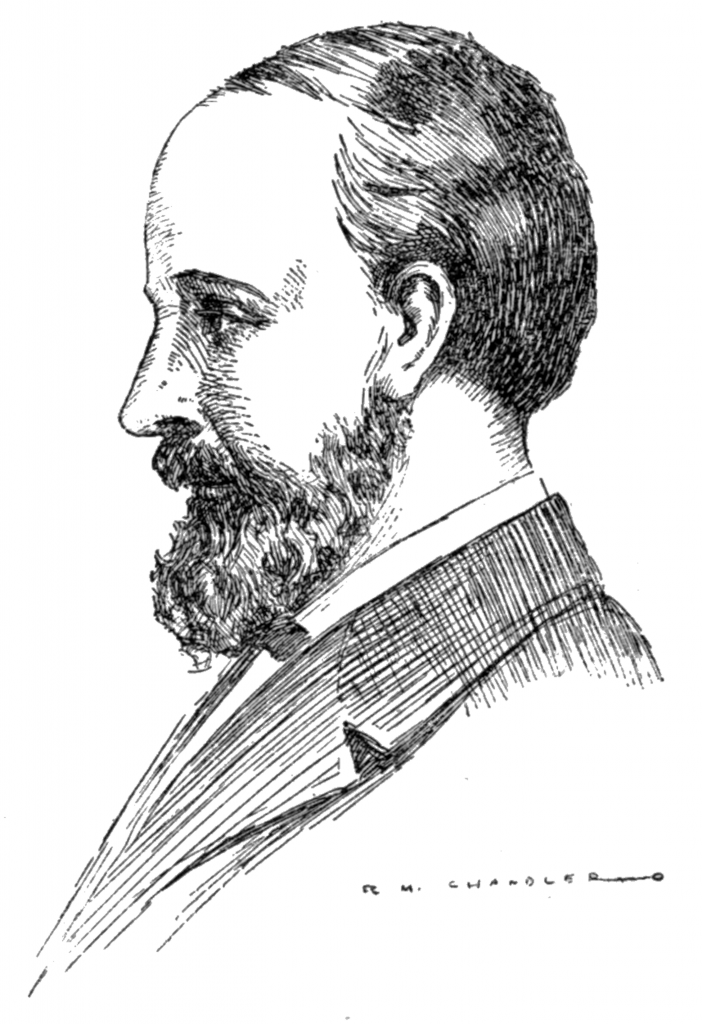

No one acquainted with the poetical literature of the late war can have forgotten the noble contributions to it of Dr. Francis Orray Ticknor, of Columbus, Ga. “The Virginians of the Valley” and “Little Giffin” are alone sufficient to prove that Dr. Ticknor was a genuine poet, and he has left behind him ( for alas! he died two years ago) a large number of ether pieces, almost all of them bearing the stamp of genius; and so admirable both in conception and execution, that for the honor of the State, no less than his own, they ought to be collected and published in book form. Dr. Ticknor was essentially a lyrist. Invariably his thought molded itself into the lyrical form, and we find in his best and characteristic verses a resonance of meter and a rhythmic ring (“as it were, the sounding of some silver trumpet,”) which fires the blood and causes the heart to beat a bold, martial measure.

Take the following poem, which has too often been published anonymously, as a brilliant illustration of its author’s power. It refers to the indomitable bravery of our “left wing” at Manassas — the First Manassas — and is truly as gallant a “war song” as ever was penned, from the age of Tyrannus to the time of Walter Scott!

OUR LEFT

First Manassas

From dawn to dark they stood

That long midsummer day,

While fierce and fast

The battle blast

Swept rank on rank away.

From dawn to dark they fought,

With legions torn and cleft;

And still the wide

Black battle-tide

Poured deadlier on “Our Left.”

They closed each ghastly gap;

They dressed each shattered rank;

They knew — (how well) —

That Freedom fell

With that exhausted flank.

“Oh, for a thousand men

Like these that melt away!”

And down they came,

With steel and flame,

Four thousand to the fray!

They leaped the laggard train —

The panting steam might stay —

And down they came,

With steel and flame —

Four thousand to the fray.

Right through the blackest cloud

Their lightning path they cleft;

And triumph came —

With deathless fame —

To “Our” unconquered “Left.”

Ye, of your sons secure,

Ye, of your dead bereft,

Honor the brave

Who died to save

Your all upon “Our Left.”

I beg my readers to remark the fiery terseness, the concentrated vigor and spirit of this fine lyric. There is not a single unnecessary word, far less line in it, from the beginning to the end. And, like all true battle-lyrics, it is passionately picturesque. One sees the contending hosts ; the flash of arms and the desperate struggle for supremacy ; the dust, the turmoil, the desperation, the horror! And just when all hope seems lost to the feebler party, how like a whirlwind we behold the “four thousand push head- long to the fray” ! In a different vein, but full of pregnant though homely humor, is Ticknor’s ballad called ‘The Old Rifleman.” Nobody, not even the most furious of the old Abolitionists, need take offense at this poem now. It has become part of the ballad literature of the country; for sectionalism in literature is, or at all events ought to be, dead. I don’t see why a Yankee soldier himself should not laugh at the description of “Old Bess’ “virtues in the shooting line.” Of course twelve years ago it was very different. “Bess” might have been considered rather personal in her attentions just then. I quote this spirited ballad entire:

THE OLD RIFLEMAN

Now bring me out my buckskin suit,

My pouch and powder too ;

We’ll see if seventy-six can shoot

As sixteen used to do!

Old Bess, we’ve kept our barrel bright,

Our trigger quick and true,

As far, if not as fine a sight,

As long ago we drew!

And pick me out a trusty flint!

A real white and blue!

Perhaps ’twill win the other tint

Before the hunt is through!

Give boys your brass percussion caps,

Old “shut-pan” suits us well,

There’s something in the spark; perhaps

There’s something in the smell!

We’ve seen the red-coat Briton bleed;

The red-skin Indian too;

We’ve never thought to draw a bead

On Yankee-Doodle-Doo!

But Bessie! bless your dear old heart! —

Those days are mostly done,

And now we must revive the art

Of shooting on the run.

If Doodle must be meddling, why

There’s only this to do —

Select the dark spot in his eye

And let the daylight through!

And if he doesn’t like the way,

That Bess presents the view,

He’ll maybe change his mind, and stay

Where the good Doodles do!

As Timrod was par excellence the war-poet of South Carolina, so was Ticknor the war-poet of Georgia. I would fain remind our generous-hearted people of what he has done (let me repeat) for their fame quite as much as his own; and thus inaugurate measures whereby the intellectual remains of a versatile, manly, yet tender genius may be collected and preserved for the benefit of coming generations! Ah, fellow-countrymen, it is an ancient truth, but

how little regarded, that the materialisms of trade and commerce and finance are not all that constitute a nation’s glory. Strengthen your trade prosperity by an alliance with the vitality of art. Do not honor exclusively (as too often you have done hitherto) your great agricultural and railroad capitalists, your heroes of the loom, the bank, the exchange, but reserve a place in your esteem and grateful remembrance for those who have wrought through spiritual and mental agencies, and whose words, with recognition, shall not die!

From the Augusta Chronicle, September 4, 1876.

One Comment