In his important 1994 work, Revival and Revivalism: The Making and Marring of American Evangelicalism, 1750-1858, the Rev. Iain H. Murray examined the periods in American church history known as the first and second awakenings. Focusing mainly on the spiritual movements in the North, Murray argued persuasively that in general the First Awakening period of the mid-18th century was characterized by an understanding of revival that was well-grounded in the teachings of the Bible, including dependence upon the Spirit of God to perform the work of conversion in the souls of men, albeit certainly in response to the diligent and faithful ministry of the Word of God. Murray observed that the view of American churchmen was basically “that what happens in revivals is not to be seen as something miraculously different from the regular experience of the church. The difference lies in degree, not in kind. In an ‘outpouring of the Spirit’ spiritual influence is more widespread, convictions are deeper, and feelings more intense, but all this is only a heightening of normal Christianity.”[1]

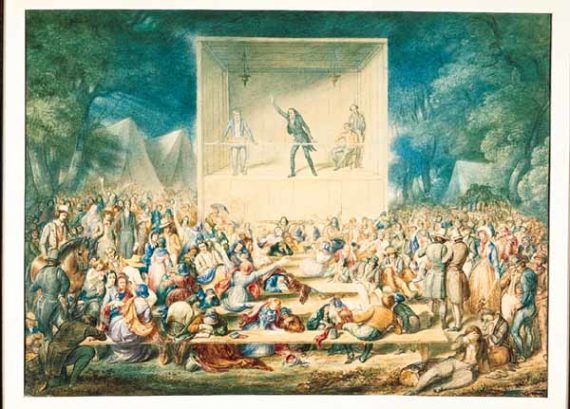

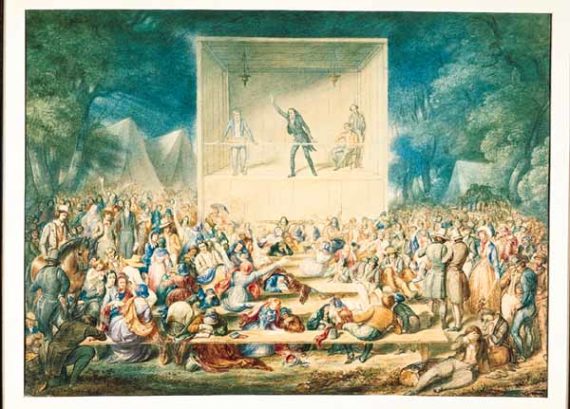

In contrast, however, the Second Awakening period during roughly the first half of the 19th century was marked – especially after about 1830 – by a trend on the part of ministers and itinerant preachers to stray beyond the traditional ordinary means of grace – the calling of sinners to faith and repentance according to the preaching of Christ’s gospel, prayer, and corporate worship including the sacraments. Rather, they began to include the use of extraordinary means, measures, or methods to encourage conversions or professions of faith on the part of those who were concerned, or ‘anxious,’ for the state of their souls. Murray acknowledged the “limited material available” to him concerning Southern revivals, a dearth that recent scholarship has done little to ameliorate concerning our understanding of revivals in the Old South during this period. The foregoing essay suggests that the Kentucky revivals of 1828 evinced at least a small-scale, halting step in the transition from the older view of revival or spiritual awakening to the newer revival-ism that within a few decades took hold generally within American evangelicalism. The national trend, however, was to some degree countered by many Southern evangelicals. In Southern Evangelicals and the Social Order, 1800-1860, historian Anne C. Loveland wrote that by the 1840s and ‘50s evangelicals in the Old South – many of whom initially had adopted some of the new measures – stepped back from what they had come to consider the contrived techniques embraced by many Second Awakening preachers and churches. And as Murray’s focus on the North suggests, those measures were practiced increasingly outside the South.[2]

The year 1828 was only one of many years in the four or five decades of the Second Awakening period during which significant outpourings of the Spirit of God were reported by observers or participants. In the South, Loveland identified various revival periods including 1822-1823 among Baptists in Virginia and the Carolinas; 1827 among Baptists, Presbyterians, and Methodists in Georgia and South Carolina; 1831-1833 among Baptists in Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia; and 1837-1839 among Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians in the Deep South.[3]

In addition to the above, the spiritual course of events during 1828 in Kentucky elicited several encouraging reports of revival in that portion of the Southern Zion, documented especially in the Presbyterian-run newspapers and church records of the day which comprised one small part of “the flood of print” and the “revolution in communications” described by historian Nathan O. Hatch in The Democratization of American Christianity. Whereas by the close of the 1820s there were well-established Presbyterian weekly (or biweekly) newspapers in Richmond, Virginia; Lexington, Kentucky; and Charleston, South Carolina; only Richmond seems to have enjoyed a viable Baptist weekly periodical in the South prior to the 1830s. Neither the Methodists nor Episcopalians in the South had weeklies prior to the 1830s, although during that decade both denominations began newspapers in Richmond and Baptists began one in North Carolina as well. In the 1820s, South Carolina Episcopalians had begun a monthly periodical, the Gospel Messenger, and Southern Episcopal Register, published in Charleston.[4]

In February 1828, the Lexington, Kentucky, Presbyterian-run Western Luminary – the earliest known religious periodical west of the Appalachians – published an extract of a letter concerning a recent revival in the New Concord Church in Nicholas County. The unidentified writer noted that about two months prior to the spiritual awakening, “about twenty of the friends of the Redeemer” had agreed to “devote a portion of each day, at twilight, P.M. to prayer to Almighty God, for the descent of the Holy Spirit upon this people.” A four-day meeting had been scheduled from a Friday through Monday, which was preceded by a day of fasting as well as prayer, presumably by the aforementioned twenty. Anne Loveland wrote that the “protracted meetings” typically favored by Presbyterians and Baptists especially after 1830 normally were four-day events held indoors, usually within a church edifice, as opposed to camp meetings which were held outdoors. In this case, New Concord’s pastor was assisted by three other ministers, and “notwithstanding the badness of the roads, and the rain which descended in torrents” during the first meeting, “multitudes attended night and day.” On the third day of meeting, which was the Christian Sabbath, or the Lord’s day, “though it rained excessively in the morning, and the wind blew a hurricane all day, yet the house was full to overflowing.”[5]

Thirteen persons were received by the church “on the profession of their faith in Christ, and one by letter.” By the close of the meeting which was extended to a fifth day, 38 more “came forward as anxious inquirers.” The writer observed that the meeting “was the most awfully solemn and interesting that I have ever witnessed. Truly the Spirit of the living God is in the midst of us.” It was interesting that despite the newspaper’s title of “Revivals in Kentucky,” the writer never used the word revival.[6]

Note also that while 13 were received by the church as members, plus one by letter presumably from a previous church attesting to the individual’s good standing, the 38 anxious inquirers were not said to have been received as members. Probably, in this case as in others, the inquirers were instructed to continue to “Seek the Lord while He may be found” in order that they might soon ‘confirm their interest’ in Christ (in an expression of the day). But the immediate reception of the 13 that professed their faith amounted, perhaps, to a new measure not practiced generally in the First Awakening period. Iain Murray wrote that many pastors reared in the traditional understanding of revival “were against treating anyone as a convert simply on profession of faith.” Ideally, the professor needed to be observed bearing spiritual fruit consistent with his or her profession before being received as a member of the church.[7]

In many cases, the description of the ingathering resulting from an ordinary means of grace ministry was tantalizingly sparse. In August 1828, the Western Luminary reported on several churches under the heading of “Revivals.” A four-day church meeting at Bethel Church in Fayette County, Kentucky – in which Lexington was situated – experienced 15 persons coming forward “to the anxious seats, as awakened and inquiring sinners.” The following entry concerned a Presbyterian church in Shelby County, Kentucky, in which following a four-day meeting “between 40 and 50 persons were added to the Church on a profession of their faith and new obedience.” In neither case was the word revival used in the description, but in the next report, the only information provided was that in Henry County in a Presbyterian church under the care of long-serving pastor Archibald Cameron, “a very interesting revival has commenced.” The Rev. Dr. Cleland provided the information for the next report, in a letter written to the editor of the Luminary. During a recent observance of the regular quarterly communion – which might be a four-day affair as had been the traditional practice of Presbyterian churches in Scotland – there were 21 members added to the church. This number was not strictly from the recent communion services but was the total that had professed their faith in Christ since the previous quarter. Pastor Cleland wrote of the work in New Providence, Kentucky, that it had “gradually, yet powerfully, progressed in this church for more than three years. O, for a continuance of this gracious work until all the ransomed of the Lord are converted and brought into the fold of our great and blessed shepherd.” In the fifth and final Kentucky church from which a report had been received, the Rev. Samuel Y. Garrison wrote to the newspaper’s editor of encouraging news from Smyrna, in Mason County. Garrison had served the church since the start of the year, having found the congregation in a low condition upon his arrival as it had been without “ministerial labours” for several years. As Pastor Garrison described, “the Lord heard their cry . . . so that he has poured out his Spirit and watered this vine with the dews of heaven.” In a recent four-day meeting, “16 persons made a public declaration of their faith in the Lord Jesus Christ, and were received into the communion of the church.” In all, 75 persons had been added to the church that year, and there were still others “anxiously inquiring the way of life and peace.”[8]

As in the above case of Fayette County, the terms anxious seats (or bench) were often mentioned in connection with revivals of the day. Generally, the reference was to a particular seating area in the sanctuary or the meeting location in which those individuals anxious or concerned for the condition of their souls were invited to sit. While the practice often has been associated with Charles Grandison Finney if not also with revivalistic or extraordinary measures, at least certain Presbyterian records document its use in the 1820s, several years before Finney began his ministry. And Methodists had employed the technique in earlier years. Soon, however, Finney became one of the foremost promoters of the anxious bench.[9]

In November 1828, the Presbyterians’ Kentucky synod, its statewide church court, reported on the gospel’s progress among its churches in the past year, calling it “a year of the right hand of the Most High.” The synod reported favorable news from more than 40 of its churches, noting an “unusual attendance upon the means of divine grace” which had been blessed “in the demonstration of the Holy Spirit.” “Some of every class and almost of every age have been called into the household of faith” among the three to four thousand newly received church members.[10]

Among the Kentucky Presbyterians, many of those received as communicants had been baptized as children. The synod stated, “It is worthy of notice that a very large proportion of these converts in early life were consecrated to God by Baptism. The work of grace among us has been silent, solemn, and in some instances awful, by reason of the presence of God, in the midst of the assemblies of his saints.” In contrast to certain popular views of the Second Awakening period, the synod added, “It has been unaccompanied with bodily exercise, or extravagance of any kind.” While implicitly recounting the use of ordinary methods or means of grace in the gospel ministry – the Bible, prayer, and corporate worship including the sacraments – the Kentucky Presbyterians acknowledged further that “various means have been employed in calling up the attention of sinners to the one thing needful, and in pointing them to the Lamb of God.” The varied means included, in many instances, separating from the congregation those who “were anxiously inquiring the way to Zion” presumably to a nearby room, building, or tent where they might “receive the instructions of the gospel in the plainest manner, and to enjoy the conversation and the prayers of the people of God.” In such cases, it might be more appropriate to refer to an anxious room rather than an anxious bench as it was clear that the individuals had been separated physically from the rest of the congregation (presumably comprised mostly of church members). The synod went on to mention the practice of private and public prayer as well as “days of fasting, humiliation, and private visitation,” the latter presumably in the homes of the anxious and which had been blessed by the Lord. In Kentucky, then, it seemed that while ordinary means predominated in the church meetings and in the homes of members and inquirers, at least one new measure soon to be associated with revivalism – the anxious room in this case instead of a seat or bench – also played a part in the reported ingatherings.[11]

The name of Charles Finney is probably the best known among the major figures of the Second Awakening period. A lesser known Northerner, and in contrast to Finney an orthodox Calvinist, the Rev. Asahel Nettleton, was used of the Spirit in Virginia during the year 1828. Like many from New England in that era, Nettleton had traveled to the South partly due to health reasons, but while in Virginia he preached extensively in Prince Edward County and the surrounding area. In October, the Western Luminary published a report from its eastern neighbor, entitled, “Revival In Prince Edward, Va.” An unnamed minister who had witnessed and promoted the work wrote:

During the refreshing from on high, which the College Church in Prince Edward has enjoyed, for some months past, forty-six members have been added to the church on a profession of their faith. In addition to this result there has been, and still remains, much of that kind, friendly feeling, which designates the holy love of the children of God, an evident advance in holiness of life among christians, and a deep, settled seriousness on the minds of the community at large. We hope the harvest is not past, though the Rev. Mr. Nettleton, who has been the chief laborer in the field, has been engaged elsewhere nearly two months.[12]

The writer went on to describe the means of grace he had observed firsthand:

As far as man can see, the principal means which God has blessed, have been, 1st, the plain truth concerning sinners and salvation, plainly told; 2d. pastoral visiting in the form of short calls upon each family, for the purpose of conversing individually, and inviting each one to attend to the great subject of religion; and 3d. the arrangement, and direction, of external circumstances, such as singing, conversation, amusements and excitements, so that they should not divert the attention from the subject, and cause the Holy Spirit to depart.[13]

The above report highlights one of the difficulties of a 21st-century assessment of mostly sparingly described spiritual matters from nearly 200 years ago. While, on the one hand, the acknowledgment of the primacy of “plain truth concerning sinners and salvation” points to an acceptance of the preaching of the Bible as the most important ordinary means of grace – still acknowledged by conservative Bible-teaching churches today – on the other hand, the mention of arranging “external circumstances” including “amusements and excitements, so that they should not divert the attention from the subject, and cause the Holy Spirit to depart” is quite unclear, if not odd-sounding, even alarming, to the contemporary Christian. Perhaps further study in local primary materials of that period might provide a clearer explanation of the meaning of penmen such as the ones in Kentucky and Virginia. But, at the least, accounts such as some of the foregoing during 1828 suggest that certain new measures – particularly the use of an anxious space for concerned souls and a corresponding readiness to receive immediately, or nearly so, the anxious who professed the faith – were being implemented, at least for a time among Southern evangelicals, adding perhaps another element to what Nathan Hatch described as a period that “left as indelible an imprint upon the structures of American Christianity as it did upon those of American political life.”[14]

[1] Iain H. Murray, Revival and Revivalism: The Making and Marring of American Evangelicalism, 1750-1858 (Banner of Truth Trust: Edinburgh and Carlisle, Penn., 1994), 23-24.

[2] Murray, Revival and Revivalism, 374-75, 415, Appendix Two; Anne C. Loveland, Southern Evangelicals and the Social Order, 1800-1860 (Louisiana State University Press: Baton Rouge and London, 1980), 79-81.

[3] Loveland, Southern Evangelicals and the Social Order, 67.

[4] Nathan O. Hatch, The Democratization of American Christianity (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 1989), 11, 226.

[5] “Revivals in Kentucky,” Western Luminary, 6 Feb. 1828, including quotes 1-2, 4-6; Loveland, Southern Evangelicals and the Social Order, 77, including quote 3; John Esten Cooke and Charles Wilkins Short, eds., Transylvania Journal of Medicine and the Associate Sciences, vol. I (Lexington, Ky., 1828), 146-48. The journal for the month of January 1828 listed “Much rain” early on the 27th in Lexington, about forty miles away; I am indebted to Janet Wall of NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information Center for Weather and Climate, Asheville, N.C., for bringing this journal to my attention.

[6] “Revivals in Kentucky,” Western Luminary, 6 Feb. 1828.

[7] Book of Isaiah 55:6, including quote 1; Murray, Revival and Revivalism, 215, including quote 2; “Revivals in Kentucky,” Western Luminary, 6 Feb. 1828.

[8] “Revivals,” Western Luminary, 6 Aug. 1828.

[9] Murray, Revival and Revivalism, 229.

[10] “Narrative Of the state of Religion …,” Western Luminary, 5 Nov. 1828.

[11] “Narrative Of the state of Religion …,” Western Luminary, 5 Nov. 1828.

[12] “Revival In Prince Edward County, Va.,” Western Luminary, 22 Oct. 1828.

[13] “Revival In Prince Edward County, Va.,” Western Luminary, 22 Oct. 1828. The writer’s reference to “amusements and excitements” is intriguing but goes unexplained. Perhaps he refers to amusements in the local area that might turn attention away from the plain truth, plainly told. But if that was the case, why include “singing” and “conversation,” which seemed to refer to the religious meeting itself, in the same list?

[14] “Revival In Prince Edward County, Va.,” Western Luminary, 22 Oct. 1828, including quotes 1-3; Hatch, The Democratization of American Christianity, 6, including quote 4; Loveland, Southern Evangelicals and the Social Order, 87. Interestingly, only a few months after the 1828 revivals in Kentucky, the issue of Christian Sabbath day (or Lord’s day) observance became a source of heated controversy between Calvinists (mainly Presbyterians but also other mainline Protestants) and the followers of Alexander Campbell – especially in Kentucky; see Forrest L. Marion, “Calvinists, Campbellites, and Clerical Usurpations: The Sabbath Controversy in Kentucky and Tennessee, 1826-1832,” in W. Todd Groce and Stephen V. Ash, eds., Nineteenth-Century America: Essays in Honor of Paul H. Bergeron (University of Tennessee Press: Knoxville, Tenn., 2005).