Delivered as the commencement address for South Carolina College, 1887.

What theme is most fitting for me present to the young men of the South, at this celebration of the South Carolina College ? What shall one, whose course is nearly run, say to those whose career is hardly begun ? In my retrospect I deeply sympathize with you in your prospect. You look to a future—a new future; I to the past—the old past. Have they no nexus? Is the New South cut off from the Old South? Is the past of our Southern land to be buried, and the new era to forget and wholly discard its memories, its ideas, and its principles? Because a sweeping revolution has upheaved its society, is all it ever believed and wrought out by its great intellects and its social and political virtue to be deemed the worthless debris of a useful convulsion, fit only to be cleared away to make place for a new order of ideas, principles, and faith ?

I do not believe it.

The old order changeth, yielding place to new,

And God fulfils himself in various way.

But in all the history of civilized man, every seemingly extinct order has contained the seeds of that which succeeds it, and the rubbish of the past is but its circumstances, its incidents. And the seeds of truth it cherished have survived in the flower and fruitage of a later polity, free only from what was hurtful or unnecessary to the better order, which it will assume, under new conditions and with new surroundings. The child is father to the man: as true in case of a nation as of the individual.

Greece conquered Troy! Ancient Troy, from her ruins, saved and planted the seed of “Ingens Gloria Trojana” upon the banks of Tiber; and Rome, the scion of Ilium, a victim of Greek prowess, avenged a slaughtered Hector by the conquest of the land of Achilles.

When Rome crushed political Greece beneath its iron heel, the seed of Greek art, philosophy, and polity sprang from underneath it to teach the victor the ideas of a civilization which has filled the modern world with its immortal glory.

Rome scattered the seeds of its splendid polity as a common heritage for the countries it subdued ; and with them the seed of that wondrous and divine system of morals, moulded into language by the master Greek tongue, which grew in every part of barbarous Europe, as at once the creator and protector of all that the modern world values as civil and political liberty.

And see one moment:

That Christianity was what? It was the indigenous product of Judea—a little realm which Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian, Grecian, and Roman powers had conquered, plundered, and ground into political and civil servitude. Moral truth never dies from the blows of brute force, but survives to teach, direct, refine, and civilize it.

Was ever a more complete conquest than that of the Norman Conqueror, eight centuries ago, over the Anglo-Saxon at Hastings? And yet, where is the Norman name to-day? In Angle-Land? Where its fame? Merged in that of the Anglo-Saxon, “a power which has dotted over the surface of the whole globe with her possessions and military posts; whose morning drumbeat, following the sun and keeping company with the hours, circles the earth with one continuous and unbroken strain of the martial airs of England.” Where is the political power of the Norman and his feudal tyranny? Surrendered to the Commons of the Saxon people, who, by a persistent devotion to freedom and to home, and a tenacious adherence to the institutional principles inherited from their ancestry, have banded the earth with the splendors of their achievements, and have made us forget their disastrous overthrow at Hastings, in the memorials of Law and Liberty which have made the Anglo-Saxon name the cherished heritage of progress and civilization to all mankind.

The battles that decide the fate of races are not fought, nor the victories won, on fields of carnage. They are fought and won within the human soul, and unless the soul surrenders, the truth cherished by man in that impregnable citadel is invincible by all the powers of earth.

Who is the only conqueror in all these human conflicts? The only victor over all is Truth !

“The eternal years of God are her’s;

While error, wounded, writhes in pain,

And dies amid her worshippers.”

Shall I advise the. young South to renew the battles of 1861 to 1865? To restore slavery? To ordain nullification or secession? To hate the Union, and struggle again for a Southern Confederacy? To maintain alienation in social, personal, or political relations with the Northern States, once our enemies, now our allies and friends in a peaceful Union?

To each and all—as man, as Virginian, as Southerner, as Statesman, as Christian—I answer a thousand times, No, no, no!

What, then?

All wars with weapons are wars of ideas! The war of the Revolution was between a centralism alien to our rights, and a localized power, their only protector!

The war between the North and the South was a conflict between ideas. Was either wholly right or wholly wrong? If not, wherein was either right? For wherein either was right, that is Truth imperishable, and to be conserved.

Slavery was the occasion of the war of 1861—not the cause. The cause was the conflict of ideas, to which slavery, as the occasion, gave rise from the intensity of feeling growing out of its importance and the momentous consequences of its abolition by the Federal Government.

Slavery as an institution of Southern life had three relations to it:

1st. As a question of property: two billions of dollars of property invested. Whether wrongfully or not, is not the question.

2nd: As a social relation: shall 8,000,000 of Caucasians and 4,000,000 of Africans live together as masters and slaves, or as co-equal citizens, in personal, social, and political rights and privileges?

3d. As a question of constitutional power: shall the general government stretch out its hand by direct or indirect means, by political legislation or political moral force, to undermine it by slow process, or to destroy it by one blow? Or shall each State manage and control the local institution by its own local will?

The first relation concerned but a small part of the people as owners of slaves—it was said, not more than 60,000 slaveholders.

The second concerned the whole of society—concerns us now, and will concern us for generations. We were like the man with the wolf by the ears—it was inconvenient to hold on, but what dangers would result to let go? “Ah! there’s the rub!” We foresaw then what we see now.

The third relation concerned the whole Union—for if the delegated authority of the Federal Government could strike successfully at slavery, with the guarantees the Constitution gave for its control only by the local authority of the States, what fence existed longer to mark the boundary between centralized power and the reserved rights and powers of the States?

The North claimed power over slavery, which the South denied. The ultimate result of that claim, the South thought (and tested its sincerity by a “resistance even unto blood, striving against” it), would destroy this vast property ; but chiefly and dangerously would subvert its society, and upturn the foundations of the Constitution between the States.

Whether this claim of power was just, or the apprehensions of its results by the South were well-founded, I need not discuss. I seek not to reopen the wounds of controversy, but to close them, after a diagnosis of the causes.

Both parties tumbled into war. It seemed inevitable. And except by the absolute surrender of one of them, can we see how it could have been avoided? A war of thoughts became a war of arms!

Underneath all the passions and mistakes and unwisdom of the period, the North and the South consciously strove for two fundamental principles in the political science of the Anglo-American race.

The North strove for Union, as the only security of each and all against external force; as the only guaranty of peace among themselves; and as the means, by unity in foreign policy, as distinguished from the separate policy of each State, of promoting our foreign trade, and the common progress and general welfare of all the States. This was a great and invaluable principle.

The South conceded all that, but strove to save the liberty of the people of each State, by preventing any interference with local rights by the Federal Government, and securing the exclusive direction of them by its local government. This was what the Colonies had won independence to secure, and what the States must conserve in this Union, or it will become a splendid centralism, dominating with absolute power the local rights and interests of the people of each State. This was a great and invaluable principle.

The Court of Mars to which both parties appealed, decided for the North against the secession of the South. We bow to the decree of the umpire to which we appealed. The contract of Union by that decree, to speak forensically, has been specifically enforced. That decree is final, and from it there is no appeal; and we desire none!

Amendments have been adopted to the Constitution by the States, and three principles have been agreed to by all the States, and are now indisputable parts of that instrument, to wit: the eternal abolition of slavery; the denial of secession as a constitutional remedy to the States; and the equal civil rights of the negro with other men, and the prohibition of a denial to him of the power of suffrage, on account of being such, or his previous condition as a slave.

With these amendments, the old Constitution is restored in all its integrity, and the Supreme Court has so decided again and again.

What, then, must the New South do? Contemn and condemn its fathers of the Old South ? Neglect their graves, deride their principles, and denounce their immorality in slaveholding? The Old South were not responsible for slavery more than England and the North. England forced it here against Colonial protest, and vessels, not Southern, brought them to our shores from Africa and sold them to us! And if the slave trade was continued until 1808 by the votes of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, they could not have made it a part of the Constitution had not Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire, with Maryland, combined with them against New Jersey, Delaware, Pennsylvania, and Virginia to make it so.

“The fathers have eaten sour grapes, and the children’s teeth were set on edge.” A former generation instituted slavery, and this generation has reaped the bitter fruits of its existence. It was our misfortune; not our fault. Theirs was the offence; ours the penalty.

Let us, then, be done with this self-crimination and recrimination. From the misfortunes, faults, and mistakes of the Old North and Old South, let us discern and rescue the Truth, buried under the wreck and rubbish of war and revolution, and exhuming it as precious seed for the civilization of the New South, do honor to the heroic martyrdom of our dead, and cling to the principles for which they died as the everlasting memorial of their great names, and as the priceless heritage of our latest posterity.

I would to-day, my young brothers, like “Old Mortality,” efface from the moss-grown tombs of our old and buried South the stains which defile them, and restore and deepen with my unskilled hand the inscriptions that Truth has chiselled there, as tributes to their genius and their statesmanship, to their moral virtues and their martial heroism. The New South, in the glory of its progress in wealth and material prosperity, will be unworthy of these gifts of Providence, and will merit only the contempt of mankind, when it shall ever learn to reject the profound political philosophy of Jefferson, Madison, Rutledge, the Pinckneys, and Calhoun, or turn with irreverent indifference from the tombs of Robert Lee, Sydney Johnston, and Stonewall Jackson!

Without detracting from the well-earned fame of Northern statesmen and soldiers, but yielding to them a just and generous admiration, let us never sink into the slough of servile self-humiliation on the one hand, or of obsequious, fulsome, and fawning flattery on the other. The North pays fit homage to its mighty dead in monuments of marble and of bronze! Let us take care to mark with honorable memorials the graves which cover the ashes of our sages, patriots, and heroes, who were the peers of any who have ever appeared in the history of mankind.

Permit me, then, to direct your minds to the Inductive Philosophy in political science (the peculiar product of Southern thought), and to the evolution, by this induction, of great fundamental principles, upon which rests what Mr. Calhoun so finely calls “the beautiful and profound system established by the Constitution.”

Much theoretic speculation has been indulged in certain schools of thought as to man in a state of nature; which is held to be a state of isolation from his species—a dreary solitude. And then the political theory results, that man enters into society upon a social compact, by virtue of which he secures certain rights and liberties upon giving up others.

All this is a fiction. The isolation of man is not his natural state. His natural condition is in society. Since Adam’s solitude, history furnishes no other instance: and fiction presents Robinson Crusoe in the fancied state of nature, from which he cries out in human agony of protest, “O Solitude, where are thy charms ?”

Society is the native air of man. He yearns for a mother’s love, a father’s care, for free commerce in thought, in which each party is enriched. With organs of speech, silence is the doom of isolation, and language the glory of the race. Music is hushed in solitude, and religious worship is cold without human sympathy. The instinct of love between young hearts dies without social intercourse to make it mutual; and parental and filial affection and friendship are forever unknown in this world which fiction creates as the arena of man in a state of nature.

Reasoning inductively, we reject this fiction and regard the facts.

Man enters society by birth, as an infant pillowed on a mother’s loving bosom, and in a home provided by a father’s honest thrift and guarded by his manly courage. Into the family home the child conies under providential order, not by an act of his own volition, and becomes at once the centre of social influences, without which his life would be brief, and under which he is reared to manhood. By nature’s law he is in society from the cradle to the grave ; from the moment he is first nourished by maternal bounty, until the death damp is wiped from his pale face by the hand of loving friendship.

Man’s state of nature is society.

This fictitious theory is not a barren one. It bears fruit in the political theory of the social compact, as the true basis and source of all relations between man and government; and that under this compact he derives his rights, and government gets its power.

Its first dogma is, that men are born free and equal.

Men are not men when born, and when born, as infants, are not free, nor ought they to be free.

Under God’s providence, by birth the human being is the weakest and most helpless offspring in the animal kingdom. He is born in absolute subjection to despotic (not tyrannical) authority. His will, his wishes, are subordinated absolutely to parental control. This is essential to his life and growth and well-being. Were he free from this power, he would perish. This despotism is secured against tyranny by a mother’s love (which is nearest to the Infinite and Eternal Love), and exercises its power for the highest good of its subject.

“The powers that be are ordained of God!” Man does not enter society under compact. He enters in subjection to the powers that are ordained of God. He does not enter as a free man; he enters as an infant, without liberty and in absolute subjection.

The dogma declares him to be born equal. Equal to what? And in what? In mind or body? To his parents and other adults ? In neither respect. Infants differ in these respects from each other, and in natural opportunities for future life.

And when grown to maturity, the difference is marked.

Races of men differ widely. Men differ in natural gifts, intellectual, moral, and physical. We have giants and dwarfs; a Hercules and a hunchback; an athlete and a cripple. In mind, we have Napoleons and Bourbons, Newtons and imbeciles. In morals, we have a Washington and an Arnold, a LaFayette and a Marat. Some men have the highest gift for music; others cannot tell one air from another. So in poetry, art, science, and philosophy.

How can Truth be built upon such a fallacy? A falsehood in fact, however beautiful the hypothesis, can afford no solid foundation for scientific investigation.

In truth, God manifests his wisdom in the creation of this infinite variety and wide diversity of the human race. Diversity of gifts makes division of labor easily possible; and the combinations of these in all human activity, most efficient for securing to each and all of mankind the largest sum of the blessings and goodness of a wise and beneficent Creator.

George Mason, of Gunston Hall, who wrote the first Bill of Eights (June 12,1776) and the first Constitution (June 29, 1776) in America, in a large degree avoids the fallacies of this dogma in the first article of the Bill of Rights of Virginia.

That declares “that all men are by nature equally free and independent.”

Now, when I am asked if I deny all freedom and equality among men, I answer, by no means; I only seek to winnow the grain of truth from the chaff of error.

Men in many thing are equal, and are equally entitled to freedom. Homo sum, et nil humani a me alienum puto!

Let our induction guide us to the just conclusion as to this drama of human life.

The germ of manhood enters the family, which is the germ of all society, in subjection to the germ of all government, that of the father, the Patria Potestas; and all this by divine ordination.

But what is this new being, who thus enters upon the stage of human activity? Does he contract, before he comes, for terms—or afterwards? Not at all. But it does not follow that he has no rights to be secured or destiny to be provided for.

He is a creature of God, gifted with capacities from his Maker, and charged with a mission of duty from Him, for which he, and he alone, is responsible. God placed him under the fostering care of absolute power, mingled with, and checked by, the tenderest love, to nurture and prepare him to discharge his solemn and awful trust to the Supreme King. Each is entrusted with talents—one with ten, another with five, another with one. “Occupy till I come!” is the divine commission to each. There is no equality in the gifts; they are diverse. There is equality between them in the trust confided, the duty required, and the right, the personal right, to be free and independent from all intrusion by any other being, in order to perform the duty and discharge the trust.

Let me briefly illustrate. The towering intellect of Bacon can only be contrasted, not compared, with that of the menial who attended him. They were not equal, but pre-eminently unequal. Yet the right of the menial to his life, limb, liberty, and property was equal to that of his noble master. The objects of right may be unequal, but the right to them be perfectly equal. The hovel of the poor is not equal to the palace of the rich; but the right of Lazarus is equal to that of Dives. In the nervous language of Chatham, “The cottage may be frail; its roof may shake; the wind may blow through it; the storm may enter; but the king of England cannot enter! All his forces dare not cross the threshold of the ruined tenement!” The title to the hovel home is as impregnable as to the princely palace!

Each man is possessed of certain capacities, the gifts of God to him for his own use, in trust for duty to the Divine King. Inter homines, each man has absolute title to these capacities and their use. Each man for himself. “To his own master he standeth or falleth.” What right has another to interfere? “Who art thou that judgest another man’s servant?” The man is God’s servant, and being such must be free from the control of all other men. His powers originally belong to God, and are given to the man in trust—as between the man and all others, his title is complete—and he must defend it against the claims of others, as a religious duty to his Maker.

The liberty which I claim for each man, therefore, does not come through social compact—or as the gift of society or of government. It is the gift of God! inalienable by himself, because that would be a breach of trust to the Divine Giver, and inalienable by any and all others, because a sacrilegious robbery of that with which he is divinely invested.

See, for a moment, how out of all this springs the right of property.

The transformation of natural objects (raw material) by human labor of brain or hands, into things useful to human need, so intermingles the original object with the labor, in the thing into which it is thus transformed, that it becomes property, and belongs to him whose labor produced the effect, as much as the brain and the hands bad belonged to him. To take without his consent the property, which is the fruit of his toil, is to claim ownership in him. It is a badge of servitude, which English and American freemen have cast off and trampled in the dust, since Magna Charta first rang out the key-note of liberty to all the world.

I think you will concede, that when I base the right of freedom upon a title from the Divine hand, I magnify and greatly exalt it above that title claimed by a shallow human philosophy, based on the conception of men—or on a contract by the man with his fellows, as to how much he may keep, and how much he must surrender.

Let me for a moment pause to indicate certain corollaries from the principles thus inductively established.

First, to take A.’s property to give to B. or to tax A. for the use of B., or to decrease the worker’s wage for the benefit of capital, or the profits of capital for the advantage of labor—all these, by direct or indirect methods are violations of the rights of man, and a tyrannical abuse of political power.

Second, neither Monopoly nor Communism, nor Agrarianism have any support, but only condemnation, from these views. For when monopoly claims of government what is not allowed to all but only to a privileged class; or when communism would seek to put the earnings of the drone and the worker into a fund for equal division among all; or when the agrarian would take the honest accretions of industry, thrift, and economy, and share in them without the practice of either virtue—these destroy the exclusive right of every man to the fruits of his own enterprise, skill, and labor, and support a claim to live by plunder, rather than by effort and self-use.

Third, when it is claimed that inequality of wealth is against justice and contrary to the true principles of free institutions, I answer there can be no greater mistake.

The parable of the talents fitly represents the relative capacities of men for enterprise and success. He who gained with his ten talents other ten, was not required to divide with him who had only five, or with the slothful who had one and made nothing. On the contrary, non-use by the last forfeited his claim to his primal gift. The idle and thriftless, as a fact, will and do lose all, and the earnest worker is entitled of right to all he can accumulate.

So far, therefore, from an inequality of condition being contrary to the equality of right, it would be the greatest violation of equality of right to enforce equality of condition.

Fourth, the application of these principles is easy to public employments and political functions.

The distinction must here be noted between private right, and public or official duties. Civil rights of men may be equal—but the right to perform public functions, being predicable only of fitness to do them, cannot be equal between those not equally fit.

All men have equal right to aspire to the Presidency, but only those equally fit for its high duties have equal right to fill it. What equal claim can he who cannot read or write assert to fill the chair of literature in your College, with the eminent gentleman who adorns it?

The man who votes, who holds public office, not only assumes to govern himself, but you. If ignorant, the power he wields may injure himself and hurt you. What right has he to undertake to do what he cannot do?

Civil Service Reform, in its real essence, consists in requiring fitness in order to filling an office. Under the spoils system, the question is not asked if Mr. Good-for-nothing can fulfil an office, but will not the office fill-full Mr. Good-for-nothing and family?

It is said that Socrates most frequently insisted, “that it is the greatest of impostures to pretend to govern and conduct men without possessing the requisite abilities.” He was the chief of Civil Service Reform.

The right of suffrage is a misnomer. Suffrage is the exercise of power, and the right to exercise it depends on fitness to do so. Intelligence to act wisely, and a common interest to act honestly, are essentials to the privilege of suffrage. Right and the power to defend right should co-exist—unless the power, through ignorance or want of interest, would be impotent for self-defence of right, or potent for self-destruction and the ruin of society.

Returning from these corollaries, I call attention to the philosophic conclusions we have reached, which are those of the greatest political thinker of the second generation of American statesmen, your own Calhoun, as great in intellect as he was great in the purity of his private life and in the incorruptibility of his public morality.

They are thus condensed in his masterly disquisition on government:

“It follows, then, that man is so constituted, that government is necessary to the existence of society, and society to his existence, and the perfection of his faculties.”

“But, although society and government are thus intimately connected with and dependent on each other, of the two society is the greater. It is the first in the order of things, and in the dignity of its object; that of society being primary, to preserve and perfect our race; and that of government secondary and subordinate, to preserve and perfect society. Both are, however, necessary to the existence and well-being of our race, and equally of divine ordination.”

“But government, although intended to protect and preserve society, has itself a strong tendency to disorder and abuse of its powers.”

“That by which this is prevented, by whatever name called, is what is meant by Constitution.”

“Having its origin in the same principle of our nature, constitution stands to government, as government stands to society.”

In other words, as society is ordained of God for man, so government is ordained for society, and constitutions are created for governments.

Mr. Calhoun then adds with perspicuous generalization from this analysis:

“Constitution is the contrivance of man, while government is of divine ordination. Man is left to perfect what the wisdom of the Infinite ordained, as necessary to preserve the race.”

Taking, then, the divinely vested endowments of the man, we see that God in his wise Providence has introduced him into society as his natural state, under a government of the Patria Potestas, the paternal government, ordained of God for his well-being and perfection. The man under his high responsibility to God is left, in this natural state, under this primal form of government, to perfect it by a constitution. God has ordained no constitution for government, but has left man in every social condition in which he finds himself to frame a constitution for his own government, which will adapt it to the purpose for which it was ordained of God, that is, man’s self-use, for the development of his nature, in order to the fulfilment of his duty to his Divine King!

Society is the school of man, its organic force is government, the expression of that force is law.

Man’s highest social duty as a religious being, bound to allegiance to his Creator, is to strive to frame a constitution, which shall best fit government to protect him in his divinely appointed mission as a creature of the Divine Power.

The primal form of government is the Patria Potestas of the family. This grows into the patriarch, then into the tribe, then into the nation. Nation, ex vi termini, indicates kinship as the bond of national life.

The paternal authority is naturally absolute. Its despotism guided by parental love is thereby saved from tyranny. But when enlarged into the organism of nationality, love as the controlling companion of power is lost, and despotism in human history becomes the synonym of tyranny.

Government thus by prescription has the vantage ground of the man. He is born under an order of things, where the organic force of society through government restrains his liberty, and constrains his action. Liberty in its struggle with power, through all ages, has had to assert the divine right in the man, against the perverted dogma of the jus divinum regum. The strife has been unequal, but as man has risen to the self-consciousness of his right, the power of the government has yielded to the stern and sturdy demands of freedom for the man—for the individual man.

Do not forget, that under God’s ordination, man as his creature is the object for whose good society and government are ordained. All power must be for him for good. Government is a means to this end for him. He must be free to work out his destiny, with no limitation on his liberty by government, except such as is necessary to the order and peace of the social relations between him and his fellows. Self-use, which does not trench on the equal rights of his fellow-men, is his inalienable right, which government cannot restrain by any legitimate use of its authority.

Hence I deduce this general canon of constitutional law: Give to man the maximum of liberty, and to government the minimum of power, consistent with the security of the peace and order of society.

The practical realization of this maxim is the great function of constitution making, which is, as we have seen, the duty of man.

Order and liberty! these are the great objects to be secured. How much power shall government have, and how much freedom shall be left to man, so as to secure his liberty in co-existence with social peace and order? That is the momentous question!

I pause a moment in this rapid research, to note an important factor in the rise and course of modern free institutions.

All ancient systems of government regarded the nation as the chief object, and the man as very subordinate. Its monarchies and its republics, alike, strove for the glory of the nation, with little regard for the rights of the man.

But Christianity came to tell man of his origin, his duty, and his destiny. He emerged from the mass to play his divinely appointed role in the drama of human life. Henceforth the man became chief, and the nation was subordinated to his good. Man is by the law of Christianity the end of all God’s providence, and governments the means by which he is helped to play his splendid part on the stage of human activity and progress.

But Christianity furnishes the moral principles which make free institutions possible. For as the individual man is impressed by its moral law in the sanctuary of his soul, he becomes self-controlled, and freely submits to that social order, which it is the function of government to maintain; and thus self-governed, he needs less of external force to bear on his action to secure the desired result of social peace; and a larger liberty to him is safely consistent with the co-existence of social order. The powers of government may be decreased, and his liberty be increased, and yet society stands secure in its peace, order, and well-being.

The religion of Christ thus has been not only the cause of modern civilization, but is the blessed source of the possibility of free institutions for all mankind.

Taking with us these important views, let me now address your thoughts to the enquiry: What constitution is best for government for the man ?

Man must frame the constitution. That is his divinely confided trust; and he must so frame it, that the government, his trustee, shall so use its powers as to secure his rights, and promote his well-being.

A society of men, composed of individuals, and aggregated for social life and to secure under government its blessings to them, constitutes what we may term, according to the language of our American political science, the sovereignty of the people. They make the constitution under which the frame of government is erected, and delegate to it the powers which are original in society, but are exercised derivatively by the government.

From this springs this great principle of American state polity : that all political power is inherent in, and is derived by government from, the people; that the people are sovereign, the government is a trustee; the people is the principal, the government but their agent; and all powers not granted by the people, through the constitution, to the government are reserved to the people and at their sole and original will; and that all laws or acts of government, not authorized by the constitution, are null, void, and of none effect.

This last was germinally announced in the 38th chapter of Magna Charta, and has borne splendid fruit in the constitutional polity of the American States. Governments are not masters, but servants. Man is the master, and is not and cannot be a slave.

But who shall be your government? To what hands will you confide the purse and the sword? To whom can you entrust the wielding of this tremendous social force, before which the single man will be impotent? Where can you find safety for liberty, when power, possessed of the national purse and with its hired myrmidons, clad in steel and weapons of war, shall array itself against the unarmed citizen in his humble home?

Your government, executive, legislative, and judicial, must at last be in human hands, and be directed by human hearts, with all the sinful propensities of selfishness to prompt its motives, to direct its policy, and to impel its power. You make them your guardians—but quis custodiet custodes?

This is your problem. How will you solve it ?

This general maxim may be offered as a solution:

The hand that holds right should wield power. This makes right safe under power. Right under such a rule need only fear suicide.

Power and right thus wedded make a government in which liberty is secure. When divorced, liberty is lost, and a despotic tyranny is inevitable.

If the men whose rights are to be affected wield the power of the government, all will be well.

It is from this maxim that the principle of representation springs in all free institutions—so strikingly in the English constitution, and more so in our American system of constitutional governments.

The people elect their representatives for a term of service, and thus, through their representatives, exercise the power which controls their right.

But you say, the man has only one vote. True, but his fellow-citizen has like interest and right with him, and no man can hurt his fellow without injury to self. That secures both and all, from the intention of mis-government. You may trust the majority not purposely to injure the people of whom they are the larger part. It is true, they may do so by a lack of wisdom. This cannot always be prevented, but in the long run, experience will indicate the error of judgment, and the mischief will be rectified.

But you will observe, I have stated that this safety in the use of representation results from each voter having a like interest with every other. Where interests and rights are homogeneous, representation may be regarded as an adequate security for liberty against power; for power, through representation, is exercised by those who hold the right and have the interest.

But suppose the rights of men in society are diverse, nay adverse, to each other. Suppose all property rights are held by a minority, and the majority have none; will the minority rights be safe in the power of the majority? In such case, you observe, power is not in the same, but in a different hand, from that which holds the right. There is no longer safety.

This is the difficult problem, and one presenting great practical difficulty in its solution.

Mr. Calhoun has, with rare felicity of expression, declared, that the solution of this trouble will be found in requiring “concurrent or constitutional majorities” in such cases, and in not allowing the rule of the mere numerical majority. That is, so organize your government that each interest shall act independently of the other, and instead of allowing that one which has the preponderance of numbers to govern that which is in a minority, require a majority of each to concur in the political measure proposed; and thus give to neither any power over the other, but by that other’s consent; and allow no action as to either, unless both concur in consent. Power and right are thus wedded, and tyranny is prevented.

This difficulty presents itself in its worst form, when the rights and interests are in different localities and separated by a geographical line, and are the growth of social conditions in territorial sections, separated by that line.

In such a case, what benefit comes of your representative principle? Who is the representative? He but voices the will of a constituency, whose right is in antagonism to the right of another constituency. The representative of neither represents the right of the other; but only his own. The conflicts of right between the sections are transferred through their representatives to the halls of legislature, and debate becomes war. The majority section prevails, and the minority section is subdued, and the rights of the one triumph over those of the other. Power reigns in victorious supremacy in one section over the rights of the other section, whose power was impotent to protect them from the alien domination of the other. The hand which wields the power over the right, in such case, is alien and inimical to the hand which holds the right, and tyranny is inevitable. The selfish greed of an alien power will oppress and destroy the rights and interests which are subject to its will, and which stand in antagonism to the rights and interests represented by that power. Representation in such a case, so far from being a shield to the imperilled rights, is a weapon in the hands of power to destroy them.

This sectional separation of power from right was the cause of the American Revolution. American rights could not be safe in subjection to the British Parliament. These free commonwealths cut the cord which bound them to the English government, and snatched the political power from the paw of the British lion, and transferred it to the talons of the American eagle.

Allow me to advance one other proposition:

It is obvious, that homogeneity of interest is more likely to exist between persons living in small localities than between those widely separated in distant regions of a continent. Hence it will be safest, that the mass of governmental power, in its distribution, should be confided to a government representing the people living within narrow territorial limits, rather than to one representing a people scattered over a continent. It is better that the municipal affairs of this beautiful city should be managed by a city government, than by the legislature of the State, or the Congress of the Union. In other words, Parnell for Ireland, you for South Carolina, and I for Virginia, would prefer that the local affairs of each be controlled by a local government of the people than by an imperial parliament in London, or an American Congress at Washington.

Let me sum up in generalization. Man has rights of various kinds, some peculiar to himself as isolated man, and others springing from his social relations.

As to those personal rights, which pertain to his unsocial being, or to his family or home, it is best, that no government should control him. Let his moral and religious life be left to himself and his own conscience, under responsibility to his God. And so as to his home and family, as far as any control is sought external to these.

As to his social relations. In his town, or county, let his rights homogeneous with those resident therein be controlled by him and them.

In his State, let his rights as her citizen, with those of others resident therein, be controlled by him and them.

In the union of States, and in those general interests and rights, which he has in common with citizens of the United States throughout the wide domain of our Union, let all such unite in a common purpose to promote the glory of a common country, and secure the liberty and well-being of men throughout our continent.

In all of this, you will see how the power to regulate right is kept in the hands of those who hold the right. General power for general interests, and local power for local interests. Order is secured, and liberty is safe!

Need I say to you, young men of the South, that this imperfect delineation of the framework for a constitutional government has found its nearest approach to realization in this great Federative Republic of free Republics?

One century ago this day, was the Federal Convention in session in Philadelphia, which framed the federal constitution. In that illustrious body, six Southern States (counting Delaware as one) were present, and never more than five Northern States at any vote. Rhode Island was never present, and New York was not present by vote for more than a month before the close of its session.

The Constitution in its organism of the government, gave to the States power in proportion to their free population and three-fifths of slaves, in the House of Representatives; and according to their co-equality of States in the Senate, and by a combination of both of these factors in the Executive Department. The war power was confided to Congress, the treaty power to the President and Senate, so that at the present moment less than twenty-five per cent, of the total population of the Union may prevent a war, and forty per cent, may advise and consent to a peace. In every branch of the political functions of the government States speak the voice of the Union.

The powers of the United States are delegated to them by the Constitution; the powers of the State governments and of the States as bodies politic are not delegated, but are reserved to them, by the express words of the Tenth Amendment.

The recent amendments make no change in this organic distribution of powers. This is “an indissoluble union of indestructible States,” in the language of the Supreme Court, uttered by Chief Justice Chase.

I have utterly failed in my purpose, if I have not established these principles not only as the law of our organic life, but as the true and essential principles of the Anglo-American philosophy, in the structure of a political system which will conserve order and safety for the whole, and liberty under self-government for each of the States.

It is sometimes asserted of late, that the war has overthrown the dogma of State Rights, and established the principle of centralized government. This is not only a political heresy, but will, if practically persisted in, be a base surrender of the essential liberties of the people. If the local governments of States for their local interests have been destroyed; if the authority of Congress over these home rights has been substituted; then liberty is dead, and despotism is supreme.

It is true, slavery is abolished forever by an amendment to which the States have consented. It is true that secession as a right is abandoned by the 14th amendment adopted by the States. But it is false to assert that the reserved powers of the States have otherwise been impaired, or the delegated authority of the federal government been increased so as to bring within its reach the essential rights of the several States. The Constitution still stands as a monument of human wisdom, in the grant of full power to the departments of the government, controlled by all the States, to manage the affairs in which all are interested; and in the full and complete reservation of the power of each State to manage by its exclusive authority the affairs in which its own people have a distinct and peculiar interest. This is self-government, and this secures liberty and prosperity and progress to each State and to the union of States.

In the consummation of this grand system of governments, under a federative union, it is the glory of the South to have taken a noble and distinguished part.

In the Convention of 1787, your Pinekneys, your Rutledge, and your Butler (an array of splendid and patriotic men), united with Virginia’s Washington, Madison, Mason, and Randolph in framing this wonderful system for order, peace, and freedom.

The South was in a minority in all branches of the government when it went into operation, except in the Senate. It was her interest, as it became her duty, to preserve in administration the reserved rights of the States, as she had done in the construction of the Constitution. The danger to the peculiar institution of her social life made her jealous of an increase of federal power; and Jefferson took the lead of that great party whose principles were based on a vigorous adherence to that constitutional distribution of powers which, while it conserved the integrity of the authority delegated to the Union, yet with equally earnest fidelity kept the local interests of each State under its exclusive control. A minority always looks more sedulously to the boundaries of power, because its safety is in maintaining them; while a majority is never jealous of an increase of power, because its rights will not be menaced by its exercise.

This is the cause for the growth of that profound insight into the principles of political science for which the Southern school of statesmen were so pre-eminently distinguished; and in the development of which Mr. Jefferson was the acknowledged apostle, and Madison, in our early history, and your Calhoun, in a later period, were the most eminent expounders.

Expurgating from that creed the doctrines of Nullification and Secession (which has been done by the late constitutional amendments), and the school from which that creed sprang should still be upheld as the best teachers of political philosophy in all parts of the country, to perpetuate a splendid union of free and happy commonwealths. I heard Mr. Calhoun thus epitomize this creed in the Senate in 1842—his clarion voice still rings in my ear: “Free trade, low duties, no debt, separation from banks, economy, retrenchment, and a strict adherence to the Constitution.”

This work of the Old South, so grand and noble, is the heritage of the New South, which it cannot throw away without a base barter of a precious jewel in its crown, for the attainment of fancied material benefits at the expense of the principles of honor and right.

Accursed, Socrates is reported to have said, be he who first made a distinction between what is right and what is expedient. No glory can come to the New South, and no real prosperity, if she repudiates the political philosophy of her ancestry, and abandons herself to the greed of gain, and adopts political principles which will prostitute federal power to the promotion of schemes of general plunder, in which she is to win her reward by taking her share of the dishonorable spoils!

But you are sometimes taunted with the shame of slavery; and the young South is restive under it.

Slavery was put upon us, and we inherited it, with its evils, as our misfortune. But I repudiate the thought that it was so dealt with by your fathers as to bring the blush of shame to the cheeks of their children.

The testimony of this generation is, that those whom we took as savages we civilized. We received them as heathen, and parted with them as Christian. Where else in the world has the African approached to Christian civilization, except under the institution of Southern slavery?

If it is said there were cruelties and barbarities connected with it, I off-set them with the general humanity of the relation of which the freedmen themselves are the witnesses—in their wonderful increase of population, in their affection and fidelity during the war, and in their confidence to-day in the friendship of former masters.

If men deride the system as a barbarism, and deny it the name of a civilization, I challenge the world to produce the peers of Washington and Jefferson and Marshall—the soldier-statesman, the leader of political thought, the greatest jurist of the continent—all slaveholders, all types of the slaveholding civilization of old Virginia! Do men gather such grapes of thorns? If barbarism bears such fruits, what advantage has civilization?

Slavery had its evils, but it bore, in spite of them, the fruitage of men as grand as any of whom history records the names.

It has passed away, and the original antagonisms in the Union between free and slave States, between the States of commerce and those of agriculture, have gone with it. Our Union embraces these varieties of industries, in such local relations as makes sectional distinctions take on other names; but so as to lead us to hope that in the future a faithful adherence to the Constitution will give us the perpetual assurance of union, prosperity, and liberty.

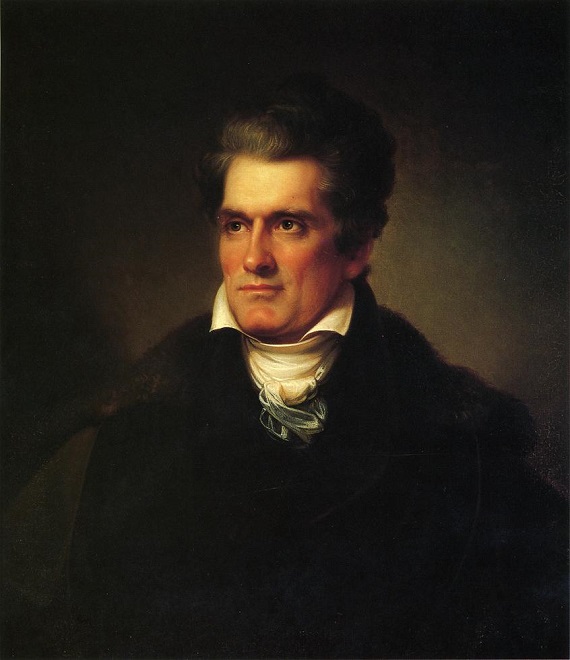

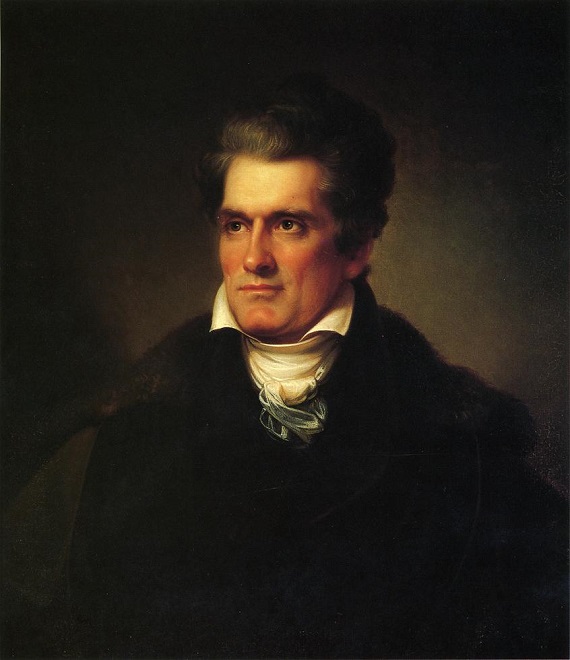

I cannot forbear, in closing this address, to vindicate the name and fame of the greatest statesman of South Carolina from an aspersion upon his character, and to present him as an illustrious type of the Old South, whom the New South should ever claim as a precious legacy from a civilization now gone forever.

Mr. Calhoun was never content to solve any problem only for its present use. His analytic mind always detected in it the germ of future and important consequences. The stars in the political sky shed their gentle light upon the quiet walks of the common thinker, but Calhoun read in them the horoscope of his country’s destiny. This was the reason that his own generation so often deemed his words the ravings of a Cassandra, while the succeeding age reads in them the inspirations of a prophet.

John Stuart Mill spoke of him (commenting on his great posthumous work) as “a man who has displayed powers as a speculative political thinker superior to any who has appeared in American politics since the authors of the Federalist.”

Mr. Calhoun, from the contemplation of the danger to his native State, being in the minority section of the Union, and exposed to the anti-siavery sentiment of the Northern States and of the world, became a deep student of political science in its application to our federal Union. His gigantic intellect, with its marvellously acute analytic powers, its breadth of generalization, and its matchless logic, was combined with a personal character without stain, and an unselfishness and elevation of public morality whose only impulse was patriotic duty.

It has been charged that his ambition led him to labor for disunion from despair of the Presidency in the Union, and in hope of it in a Southern Confederacy. I feel that I have the power to negative this imputation by the mention of an incident of which I was a personal witness, and the record of which on this fitting occasion I owe as a duty to his memory and to his people, and to the truth of history.

About the 1st of March, 1850, Mr. Calhoun was confined by the sickness of which he died on the 31st of the same month. His feeble health was the result of mortal disease. He was 68 years of age. The evening shadows of a great life were upon him, and the night of death was at hand.

I knew, admired, and loved him. I had seen him several times in that period when the famous compromise measures of Mr. Clay were under debate, and when the Union was shaken to its deep foundations by the slavery agitation. The great triumvirate—Webster, the splendid orator, Clay, the imperial leader, and Calhoun, the great thinker—were arrayed in the discussion of the fearful issue. The world knew Calhoun was dying; and a few days afterwards heard the words of his last speech read by Mason, of Virginia, to the utterance of which the voice of the statesman of Carolina was unequal.

A lady of a Northern State, of distinguished family, and with talents worthy of her lineage, had been for thirty years, and was still, a devoted friend of Mr. Calhoun. She idolized his genius, and loved him for his noble character and for his pure, and unstained devotion to public duty.

She met me (for I esteemed her by personal and inherited regard) on the day named, and asked me to go with her to see Mr. Calhoun. I gladly assented, and we went to his home, which was the house now the residence of the distinguished Mr. Justice Field, of the Supreme Court. We were admitted, and Mr. Calhoun came from his room into the hall to greet his cherished friend.

They met as brother and sister; and we entered his chamber— the same in which he died. He was wasted by disease, and was very weak. His long grey hair was combed back from his emaciated and pallid face, and fell in heavy masses upon his shoulders, as his head rested languidly upon the back of his large arm-chair. His wonderful eyes flashed and blazed with their old light, as if through them we saw the burning soul within.

Mrs.——- sat by his side, and asked about his health, and he replied with enforced cheerfulness, his face glowing with pleasure at the presence of his friend.

She said: “I fear, Mr. Calhoun, you allow your feelings to become too much excited by public affairs.” He replied : “No, not excited; only intense.” Then, laying her band gently on his arm, as it rested on his chair, she earnestly asked: “Mr. Calhoun, can nothing be done to save the Union?” The play of his features ceased; they became fixed and rigid. Gloom, deep and sombre, settled on his face. His eyes looked out into the future with that sad and solemn expression so peculiar to him, and which, then seen, I can never forget. He said, in substance: “You know, madam, I have always told you that there was no feeling stronger than the love of union, except the conscious need of the South to protect its social institutions from danger and violence.” She then asked with increased anxiety in her tone: “Mr. Calhoun, cannot the Missouri Compromise save it?” I shall never forget the deep sincerity of his expressive countenance as, with solemn earnestness, he replied (I give the ipsis-sima verba): “With my constitutional objections, I could not vote for it; but I would acquiesce in it, to save this Union!”

Young gentlemen, graduates of this learned College, as young men of the New South, I pray you to cherish the memories of the past glory of South Carolina, and of its splendid historic characters. Cling to the political philosophy of her most illustrious son, and to the federal Union, which he loved with intense admiration. Press forward in the race of progress with courage and persistent zeal, undaunted by difficulties, undismayed by past misfortune, and deaf to the seductive allurements of false principles to leave the path of truth and honor for the devious policies which promise place and preferment at the expense of justice and right. Build up your institutions for the higher education, that your young men may be prepared by labor, study, and discipline to discharge life’s duties, and that in the arena of intellectual and moral, conflicts you may compensate for the numerical decrease in the power of the South by the exaltation of the quality of her manhood. Take the revenues with which Providence has endowed your State from the mineral deposits in her bosom to endow her colleges and schools for the higher development and nobler, training of her children. Keep close to moral principles in private and public life. And thus you will make the temple of the New more magnificent and noble than that of the Old South; and take a place worthy of both, in promoting the free institutions of these States, the glory of the Union, the liberty and happiness of all the people of our common country, and the progress and civilization of mankind !