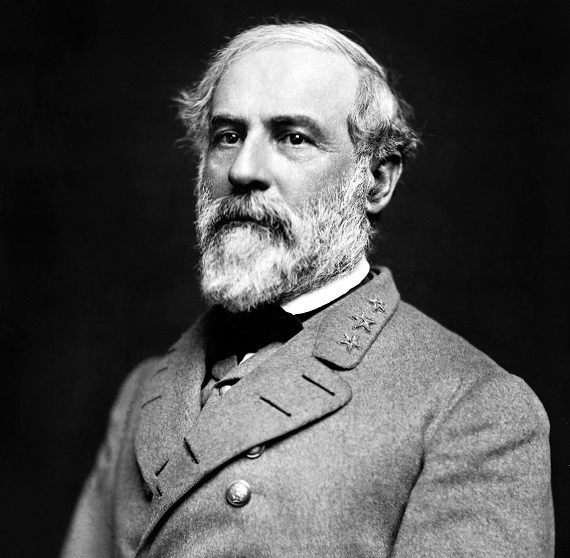

I was disappointed to hear of the demands of a group of Washington & Lee law students to ban the flying of the Confederate battle flag and denounce one of their school’s namesakes, General Robert E. Lee, as “dishonorable and racist.” This latest controversy appears to be yet another example of the double standard and prejudice against anything “Confederate.” Why, for instance, is there outrage against Lee, but not George Washington, one of the wealthiest slaveowners of his time? Why is there outrage against the Confederate flag, which flew over slavery for four years, but not the American flag, which flew over slavery for eighty years? I would like to right the multitude of wrongs which have been perpetrated against Lee’s legacy in particular and Confederate history in general. Hopefully, these truths will provide an appreciation of the complexity of the issues, principles, and participants in the “Civil War.”

First, Lee deplored slavery, describing it as a “moral and political evil” in a letter to his wife, Mary Anna. Lee told her that they should give “the final abolition of human slavery…the aid of our prayers and all justifiable means in our power,” praying for “the mild and melting influence of Christianity” over “the storm and tempest of fiery controversy” driving America to disunion. Lee elsewhere called slavery a “national sin” for which he feared America would be punished. “If the slaves of the South were mine,” Lee wrote to Bishop Joseph P.B. Wilmer, “I would surrender them all without a struggle to avert this terrible war.” Lee himself was never willingly involved in the slave economy. When his wife inherited some slaves through her father-in-law, Lee freed them in accordance with his wishes, and stayed in touch with many of them. Near the end of the war, Lee supported the late General Patrick R. Cleburne’s revolutionary plan to emancipate and compensate any slaves who enlisted in the Confederate army, along with their families. Lee recommended that arming and freeing the slaves be followed by a “well-digested plan of gradual and general emancipation.” After the war, Lee endorsed emancipation. “So far from engaging in a war to perpetuate slavery, I am rejoiced that slavery is abolished,” Lee told Pastor John Leyburn. “I would cheerfully have lost all I have lost by the war, and have suffered all I have suffered, to have this object attained.” In a correspondence with Lord Acton, the great English classical liberal, Lee said, “Although the South would have preferred any honorable compromise to the fratricidal war which has taken place, she now accepts in good faith its constitutional results, and receives without reserve the amendment which has already been made to the Constitution for the extinction of slavery.” According to Lee, emancipation was “an event that has been long sought, though in a different way, and by none has it been more earnestly desired than by citizens of Virginia.” The fact that the Confederacy’s champion was an enemy of slavery and proponent of emancipation should force everyone to question what they assume the Confederate flag symbolizes – slavery and hate or independence and honor?

Second, Lee initially opposed secession, but his loyalty to his native state – the Commonwealth of Virginia – surpassed his loyalty to the abstraction of the Union. “With all my devotion to the Union and the feeling of loyalty and duty of an American citizen,” Lee confessed to his sister, Anne, “I have not been able to make up my mind to raise my hand against my relatives, my children, my home.” Although Lee considered secession to be wrongful, he could not countenance a government based on force of arms rather than consent of the governed. “I can anticipate no greater calamity for the country than a dissolution of the Union,” Lee informed his son, George. “Still, a Union that can only be maintained by swords and bayonets, and in which strife and civil war are to take the place of brotherly love and kindness, has no charm for me.” When invited to lead the Federal invasion of the Confederacy – which, as President Abraham Lincoln painstakingly affirmed, was solely for “preserving the Union” rather than “freeing the slaves” – Lee declined and resigned his commission in the U.S. Army. “Save for the defense of my native state,” Lee replied to Washington, D.C., “I never desire again to draw my sword.”

Third, Lee did not believe he was fighting for the particular issue of slavery, but for the foundational principles of American freedom – self-government, independence, and the constitutional rights of the states. As the Confederacy rejected three offers from Lincoln to exchange submission to the Union for the protection of slavery, Lee’s convictions were confirmed. “Our sole object,” Lee wrote to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, “is the establishment of our independence and the attainment of an honorable peace.” Before his very first battle at Cheat Mountain, Lee did not encourage his men to fight for slavery, but for home, hearth, kith, and kin. “The eyes of the country are upon you. The safety of your homes and the lives of all you hold dear depend upon your courage and exertions. Let each man resolve to be victorious, and that the right of self-government, liberty, and peace shall find in him a defender.” Lee supported states’ rights not because they protected slavery, but because, as the Founding Fathers understood, they were the “safeguard to the continuance of a free government” and “the chief source of stability to our political system.” As Lee explained to Acton, “The consolidation of the states into one vast republic, sure to be aggressive abroad and despotic at home, will be the certain precursor of that ruin which has overwhelmed all those that have preceded it.” Lee further noted that George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, both of whom were secessionists in their day, opposed “centralization of power” as the gateway to “despotism.” According to Lee, “The South has contended only for the supremacy of the Constitution, and the just administration of the laws made in pursuance to it.”

Fourth, Lee faithfully upheld the time-honored laws of just, civilized warfare. Although always outgunned, Lee defied the odds and outfought his enemies with a special Southern blend of gallantry and audacity. Despite his brilliance, however, Lee abhorred the death and destruction of war. “It is well that war is so terrible,” Lee remarked to General James Longstreet on the eve of triumph at the Battle of Fredericksburg, “otherwise we should grow too fond of it.” One Christmas Day, Lee reflected on the evil of war in a letter to his wife. “What a cruel thing is war; to separate and destroy families and friends, and mar the purest joys and happiness God has granted us in this world; to fill our hearts with hatred instead of love for our neighbors, and to devastate the fair face of this beautiful world! My heart bleeds at the death of every one of our gallant men.” Despite the systematic atrocities which Federal armies inflicted upon the South – Northern leaders spoke chillingly of “extermination” and “repopulation” – Lee never succumbed to the temptation of retaliation. In both of his invasions of the Union, undertaken to force Federal invaders out of war-torn Virginia, Lee expressly forbid any depredations against the person or property of civilians. Upon crossing the Potomac into the occupied Old Line State, Lee declared to the Marylanders that “regaining the rights of which you have been despoiled” was his mission. “We know no enemies among you, and will protect all of every opinion,” avowed Lee, in stark contrast to the Federal military dictatorship. “It is for you to decide your own destiny, freely and without constraint.” Before entering Pennsylvania, Lee said, “I cannot hope that Heaven will prosper our cause when we are violating its laws. I shall, therefore, carry on the war in Pennsylvania without offending the sanctions of high civilization and Christianity.”

Fifth, after the war, Lee was a leading figure in urging reconciliation between the North and the South. “All should unite in honest efforts to obliterate the effects of war and restore the blessings of peace,” urged Lee. “They should promote harmony and good feeling,” as well as “qualify themselves to vote and elect…wise and patriotic men who will devote their abilities to the interests of the country and the healing of all dissension.” According to Lee, “I have invariably recommended this course since the cessation of hostilities, and have endeavored to practice it myself.” Instead of the many lucrative offers he received after his surrender, Lee accepted the presidency at the humble Washington College because he believed he had a duty to prepare for peace the young men whom he had led in war. “I have a self-imposed task which I must accomplish. I have led the young men of the South in battle; I have seen many of them die on the field. I shall devote my remaining energies to training young men to do their duty in life.” In his new command, Lee’s goal was “to educate Southern youth into a spirit of loyalty to the new conditions, and the transformation of the social fabric which had resulted from the war, and only through a peaceful obedience to which could the future peace and harmony of the country be restored.” Lee’s efforts ultimately saved the small and struggling school, so it was only fitting that after his death the college was renamed in his honor. Lee forgave the Northerners who pillaged, burned, and conquered his country, as well as maimed and murdered his compatriots. “I have fought against the people of the North because I believed they were seeking to wrest from the South its dearest rights,” explained Lee, “but I have never cherished toward them bitter or vindictive feelings, and have never seen a day when I did not pray for them.” If only Lee’s modern-day detractors were capable of such grace.

President Theodore Roosevelt described Lee as “the very greatest of all the great captains that the English-speaking peoples have brought forth.” Prime Minister Winston Churchill referred to Lee as “the noblest American who had ever lived and one of the greatest commanders known to the annals of war.” According to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “We recognize Robert E. Lee as one of our greatest American Christians and one of our greatest American gentlemen.” When criticized for his admiration of Lee, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower did not pander for popularity, but stood for his beliefs:

General Robert E. Lee was, in my estimation, one of the supremely gifted men produced by our nation. He believed unswervingly in the constitutional validity of his cause, which until 1865 was still an arguable question in America. He was thoughtful yet demanding of his officers and men, forbearing with captured enemies but ingenious, unrelenting and personally courageous in battle, and never disheartened by a reverse or obstacle. Through all his many trials, he remained selfless almost to a fault and unfailing in his belief in God. Taken altogether, he was noble as a leader and as a man, and unsullied as I read the pages of our history. From deep conviction I simply say this: a nation of men of Lee’s caliber would be unconquerable in spirit and soul. Indeed, to the degree that present-day American youth will strive to emulate his rare qualities, including his devotion to this land as revealed in his painstaking efforts to help heal the nation’s wounds once the bitter struggle was over, we, in our own time of danger in a divided world, will be strengthened and our love of freedom sustained.

If General Joshua Chamberlain of the Army of the Potomac, who fought against Lee in victory and defeat, could bring himself to salute the Army of Northern Virginia as it surrendered its arms and furled the flag it had borne on so many battlefields, then the least we can do today is let Lee rest in peace.

History is a vast and intricate tapestry upon which each generation weaves its story. Every time a thread of that tapestry is torn away, we lose a priceless piece of our heritage and our destiny. We are all free to hold our own opinions, of course, but we are not free to force those opinions on others by purging history to conform to the dictates of “political correctness.” The “Civil War” was not a morality play between a righteous North and wicked South, but a national tragedy with good and evil on both sides. Whatever one’s views of this decisive crossroads in American history, it must be admitted Lee was a man of sterling integrity and iron bravery who was fatefully engulfed in the “fiery ordeal” which he so very feared. Let us honor Lee’s last wishes and choose reconciliation over recrimination.

2 Comments