This piece was originally published in the New England Quarterly in 1935.

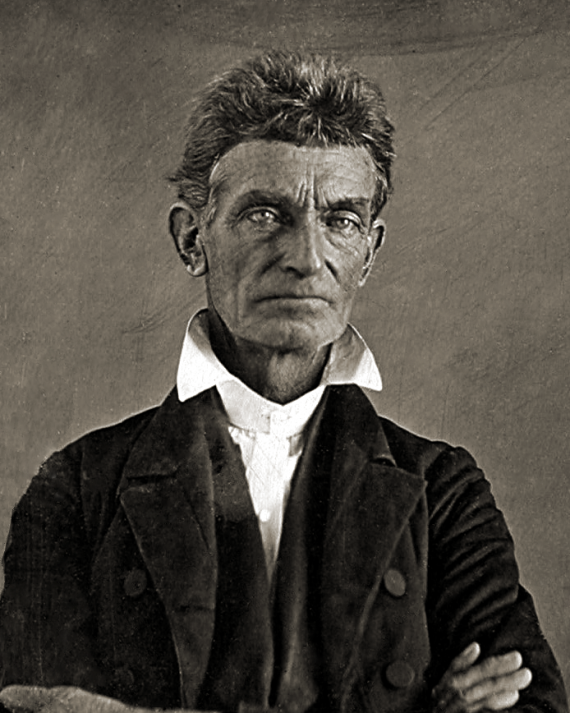

In December 22, 1859, an extra train arrived at Richmond bringing over two hundred medical students from Philadelphia. It was the hegira of southern students from the North following the excitement of John Brown’s raid. The faculty and students of the Richmond Medical College, the town council, and the Southern Rights Association exultantly welcomed them. All formed in procession and marched past the beautiful capitol designed by Jefferson to the governor’s mansion. The armory band preceded them playing martial and stirring airs. Here they listened to Governor Henry A. Wise, standing on his porch and indulging in a tirade of incandescent southern oratory. One of the students gracefully responded. Then they retired to the Columbian Hotel, where the hospitality of the Old South had prepared ” a beautiful collation ” for them.[1]

Governor Wise, fond of magniloquent phrases, said, ” Let Virginia call home her children! ” He assured them that they had acted wisely in leaving a hostile community to build up southern schools and rebuke the North for its fanaticism. Thus the reproach so often made against the South, that negro slavery paralyzed learning and science, would be proved untrue. In that perfervid way of his, he said:

Let us employ our own teachers, (applause) , especially that they may teach our own doctrines. Let us dress in the wool raised on our own pastures. Let us eat the flour from our own mills, and if we can’t get that, why let us go back to our old accustomed corn bread. (Loud applause) .[2]

The migration northward of many young southerners to study in the schools and colleges had long been gall and wormwood to the fire-eaters. Yet the pull of northern colleges was too strong to be resisted. Even the ardent pro-southern Governor Wise had been educated at Washington College, Pennsylvania. Calhoun had received his fine training at Yale and Litchfield; Robert Toombs had studied at Union College; Judah Benjamin, at Yale; and Jefferson Davis, at West Point. At the University of Pennsylvania, out of the four hundred and thirty-two students attending in 1846, two hundred and sixty-five were from the South, mostly medical students.[3]Yet these northern colleges, as Professor Arthur Cole has pointed out, had slight success in nationalizing the southern students who attended them.[4] Such an alarming patronage of northern institutions by the gifted youth of the South seemed to be a confession of weakness in the idyllic slave régime, as though the repression of free thought in the South had dwarfed her institutions of learning. But there was a very present practical danger in the sons of southern planters attending northern colleges. They would be exposed to ” the pernicious ideas ” prevalent in the North.

What were these ideas which seemed dangerous to southern minds? ” Parson ” Brownlow, editor of the Knoxville Whig, answered the question in his terse, vivid language. He proposed an organization called ” the Missionary Society of the South, for the Conversion of the Freedom Shriekers, Spiritualists, Free-lovers, Fourierites, and Infidel Reformers of the North.” [5] His catalogue of the pernicious ideas beyond the Potomac, however, was far from complete. In the Chardon Street Convention of the Friends of Universal Reform at Boston (1840) , the ” lunatic fringe ” of the reform movement held high carnival. Here there was gathered, according to Emerson, a pandemonium of the northern ” isms,” Muggletonians, Dunkers, come-outers, Seventh-Day Adventists, strident feminists, abolitionists, Unitarians, philosophers, and many persons whose church was a church of one member only.[6][7][8] The North had become a germinating centre for feverish reform movements and strange cults. Boston was regarded in the southern states as the capital city of ” the isms,” although western New York was almost as preeminent in radicalism.7

The southern people, emphasizing the common sense of plantation life, looked more with amusement than alarm at the antics of the northern reformers. When the Fox sisters began to give their seances in New York about 1850, they were irreverently referred to in the South as the ” Knocking Girls of Rochester.” [9] The spiritualist craze in the North, leading to numerous spiritualist circles and the establishment of the Spiritual Telegraph, found no echo of credulity in the South.[10] When the feminists held a convention at Seneca Falls, New York, and drew up a ” Declaration of Independence of Women ” that followed closely the great document of Jefferson, the South was disposed to look on the humorous side of the movement. An article in De Bow’s Review, in 1857, entitled ” Black Republicanism in Athens,” contained a witty satire on the bloomers and strong-minded women of the North. The author compared them to the women of the Eccleziazusæ. 10 The Sons of Temperance founded in Teetotaler’s [11]Hall, New York, even secured many converts in the South, but ” Maine-lawism,” or the prohibition law imposed on the state of Maine by Neal Dow, in 1851, was spoken of with scorn, for it invaded personal liberty.

The South confronted the various extravagances of the reforming zeal of the North with aristocratic detachment, regarding them as middle-class enthusiasms. Both sections were deeply touched by the romantic movement of the time. In the North, romanticism manifested itself in a passion for making over society according to the dreams of perfectionists, Fourierites, feminists, abolitionists, and transcendentalists. In the South, on the other hand, the romantic movement looked to the past for its inspiration, to the dream of a Greek democracy, or to the feudal charm of Sir Roger de Coverley days.ll Consequently the Oneida Free Love Colony and Trialville in Ohio were unthinkable below the Potomac. They furnished a happy label, however, for use against the Republicans in 1856, ” Free Love and Fremont.” [12] The South was almost wholly free from disturbing social adventures. Frances Wright had attempted a radical colony of negroes and whites at Nashoba, Tennessee, and the Icarians had sought to found a utopia of communism in Texas, but both perished on southern soil.[13] To most southerners they were mere names, the names of far-away vagaries. But reformers like Harriet Beecher Stowe and the English feminist, Harriet Martineau, aroused the South to unchivalrous epithets, for they had cut southern sentiment to the quick in their strictures on slavery and the morality of southern men.[14] Two of the corrosive ideas of the North, skepticism and abolitionism, were regarded as endangering the very foundations of southern society. Unfortunately they were not met by the serene warfare of Thomas Jefferson, truth fighting error, unassisted by force.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century skepticism was prevalent among the aristocratic and cultivated planters. The South had many cultural contacts at the time with England and the continent. The reading of the French and English skeptics and deists was a fashionable pastime.[15] Even as late as 1828, Elisha Mitchell came across several deists and freethinkers in the course of a geological tour of North Carolina. One of these quaint deists had been elected senator seven times from Onslow County, despite his free-thought.[16] Buckingham, during his travels in the slave states (1841) , attended the public funeral of a recently converted deist at Athens, Georgia. This gentleman, Judge Clayton, was a graduate of the University of Georgia and its most zealous patron. Until the year before his death he had openly avowed himself a deist without affecting his honorable standing in society. But such men were the relics of a by-gone century.[17] After 1835 deists and skeptics disappeared in the South. In that year President Thomas Cooper, ” the great apostle of Deism,” was driven from South Carolina College and a new chair, the professorship of the evidence of Christianity, was created to instill correct doctrine in the minds of southern youth.[18] Thomas R. Dew, president of William and Mary College, wrote the epitaph of skepticism in the South in an article for the Southern Literary Messenger (1836) .

Avowed infidelity [he declared] is now considered by the enlightened portion of the world as a reflection on head and heart. The Humes and Voltaires have been vanquished from the field, and the Bacons, Lockes, and Newtons have given in their adhesions The argument is now closed forever, and he who now obtrudes on the social circle his infidel notions manifests the arrogance of a literary coxcomb, or that want of refinement which distinguished the polished gentlemen.[19]

The older liberalism of the South, departure of which was thus announced, was the delicate fruit of a colonial aristocracy, different from the cotton-capitalists of a later epoch.

In this later stage, orthodoxy in the South was threatened by two new sources of danger, one proceeding from Europe, and the other from New England. The researches of Sir Charles Lyell, around 1830, cast a disturbing light on the Mosaic account of the origin of the world. In New England arose the refreshing liberalism of the Unitarian and transcendental movements. During the struggle against slavery, also, the New England radicals directed resounding blows against the literal interpretation of the Bible and the authority of conservative ministers.

The recent study of geology, involving an examination of the strata of the earth containing remains of the different orders of animal life, naturally turned men’s thought to the origin of man himself. By 1845, the knowledge of Lamarck’s theory of the transmutation of the species had penetrated the South. In 1854, Josiah C. Nott, a professor in the University of New Orleans, published his Types of Mankind, which denied that all men came from a common ancestor. The theory had been advanced in the South that the negro, not the lordly white man, may have descended from a chimpanzee or orangutan.[20] On the eve Of the Civil War, notices of Darwin’s theory reached the South. The editors of the University of North Carolina Magazine noted the reception, in 1860, of copies of the Westminster Review and the London Quarterly Review containing articles on Darwin’s Origin of the Species, but they did not comment on the startling hypothesis of evolution.[21]The absorbing questions of politics and secession at this time overshadowed any interest in a bizarre theory.

The reaction of the South to the flood of light which science threw upon the sacred mysteries was that of fear and intolerance. In justice to the South, it must be said that the conservatives of New England also vehemently resisted the iconoclastic tendencies of the new science. Professor Silliman, of Yale, tried to make the findings of geology tally with the facts of Genesis, and for this purpose he drew up a table of coincidences between the two. It was a scholar in a southern state, Dr. Thomas Cooper, of South Carolina College, who, in a pamphlet On the Connection between Geology and the Pentateuch (1833) , rebuked Professor Silliman for his ” absolute unconditional surrender of his common sense to clerical or. thodoxy.” [22][23] Cooper, however, had received his early education in England and was an exotic plant in the southern states. Much more representative of the southern point of view was the criticism of Lamarck’s theory of the transmutation of the species by a reviewer in the Southern Literary Messenger (1845) : ” Grant to Lamarck the slightest possible transmutation of the species, and you have no good reason to deny that a monkey was your forefather.” 23 Even Josiah Nott’s theory of the diverse origins of the races was not accepted in the South, although such a doctrine of racial inequality strengthened the southern argument for slavery. This radical theory was held to be a flat contradiction of revelation, and its supporters were no better than Tom Paine or Voltaire.

Attacks on infidelity and skepticism became a favorite theme of commencement speakers in the colleges of the South. One of the most gifted scientists the Old South produced, Matthew Fontaine Maury, took up the cudgels in behalf of orthodox religion in an address before the students of the University of Virginia (1855) . In this address, entitled ” Science and Religion,” he clung tenaciously to the literal interpretation of the Bible. He maintained that the Mosaic account of creation was correct, and that Job was a learned book on science. He smoothed out the inconsistencies between the findings of science and the account of revelation by the following process of reasoning: ” If the two cannot be reconciled, the fault is ours, and is because, in our blindness and weakness, we have not been able to interpret aright either the one or the other.” [24] The prevailing attitude of colleges toward skepticism at this time was expressed in the rule at the University of North Carolina that if any student denied the being of God or the divine authority of the Scriptures, or tried to promulgate any principle subversive of Christian religion, he should be dismissed.[25] Such regulations for southern students of ante-bellum days were hardly necessary, for student opinion was strikingly conformist.[26] In fact, attending camp-meetings was a major sport among the students.

From New England emanated a current of radicalism that caused even greater opposition below the Potomac than the theories of Lyell and Lamarck. It was not the impact of a new theology that created disturbance. The teachings of the Unitarian leaders, William Ellery Channing and Emerson, scarcely penetrated the frontier of the slave states. According to the census of 1860 only one of the two hundred and sixtythree Unitarian churches in the United States was situated in the South-. [27] There was one remarkable southerner, however, who read Emerson’s works and was converted to Unitarianism, Moncure Daniel Conway of Falmouth, Virginia. After studying at Harvard, he had a distinguished career as a Unitarian minister and reformer. His father reflected the point of view of his section when he wrote to Conway expressing his pain at such ” horrible views on the subject of religion. [28]James Henley Thornwell, perhaps the most intellectual divine of the Old South, studied at Harvard a short while in 1834, and wrote a most intolerant criticism of the Unitarian faith dominant there. To a friend in his native state of South Carolina he wrote:

I room in Divinity Hall, among the Unitarian students of Theology; for there are no others here. I shall expect to meet and give blows in defence of my own peculiar doctrines [Presbyterian]; and God forbid that I shall falter in maintaining the faith once delivered to the saints. I look upon the tenets of modern Unitarianism as little better than downright infidelity. Their system, as they call it, is a crude compound of negative articles, admirably fitted to land the soul in eternal misery.[29]

But southerners were shocked more by the iconoclastic views of Garrison and his coterie of abolitionists than the mild liberalism of the Unitarian and Universalist churches. In 1848 Garrison and his followers held an anti-sabbath convention in Boston. The call for this radical assembly, published in the Liberator, declared the sabbath to be an exclusively Jewish institution, that no day of the week waö holier than any other, and that laws which enforced sabbath observance were a shameful act of tyranny.go Five years later, a Bible convention was held at Hartford, Connecticut, to inquire into the authenticity and authority of the Jewish and Christian Scriptures. In this assembly, Garrison introduced resolutions denying that the Bible was the literal word of God, and declaring that the Scriptures ” are to be as freely examined, and as readily accepted or rejected, as any other books, according as they are found worthless or valuable.” 81 In his pulpit at Boston, Theodore Parker bitterly attacked the slave-holders and at the same time preached a religion which rejected miracles. Thus Garrison, Parker, and Wendell Phillips were regarded with extreme aversion in the South as infidels of the most dangerous tendency. -rhe union of abolitionism and religious radicalism in the North caused southern planters to cleave all the more obstinately to the literal interpretation of the Bible.32 This attitude was strengthened by a similar reverence for interpreting the constitution strictly — and literally.

The Mason and Dixon line, however, possessed no magic property of separating the religious liberals from the religious conservatives. In the hinterland of Pennsylvania many of the farmers were living in the dark ages of belief. On their great red barns was painted the sign of the ” hex ” to ward off evil spirits, and ” hex ” doctors practised a primitive superstition. In New England, also, the conservatives had a fanatical regard for the sabbath and for orthodoxy in religious beliefs. Students of Trinity College, at Hartford, tried to break up the Bible convention of the radical abolitionists in 1853 by stamping, groaning, and cursing, and derisive laughter. Even some of the most respected leaders of thought in New England assumed a conservative attitude toward doctrines and scientific discoveries that tended to disturb religious dogma. William Ellery Channing, one of the greatest religious revolutionaries of his day, was reluctant to abandon his belief in the supernatural element of the old religion, which was rejected by radicals of a younger generation.83 When Darwin’s theories were introduced into New England, Professor Louis Agassiz, at Harvard, and James Dwight Dana, at Yale, opposed them — partly because of the influence of religious feeling.

On the other hand some brave free-lances in the South dared to hold heretical views about religion, as Samuel Janney, president of the Virginia secession convention, Charles Fenton Mercer, John Minor, and Edmund Rumn. Edmund Rumn has recorded in his diary that whoever should venture to use his own judgment and disagree with the interpretation of the Bible by the preachers in Virginia would be immediately suspected and charged with opposing the Christian religion. Ruffm’s own children thought that his rejection of the commonly accepted interpretation of the Bible was a grave delinquency. He was effectually silenced from discussing religion at all by the intolerant atmosphere of his native state, and he recorded his surrender to the forces of intolerance by resolving to try to be silent on religion. Francis Lieber, for twenty years professor at South Carolina College, was another sturdy rebel against orthodoxy. In 1853, he wrote that a drunken fellow in the legislature had moved to inquire into his orthodoxy, but the motion was laid on the table. Despite his magnificent intellect he was defeated for the presidency of the college in 1855 because he was not a thorough-going Calvinist and was suspected of abolitionism. To a friend in the North, he wrote an ironic letter explaining his rejection: ” What a man I would be had I become a Methodist! [30]

The fear of skepticism in the South was not to be compared to the exaggerated fear of New England abolitionism. The danger of stirring discontented slaves to revolt constituted an ever-present ” Black Terror ” in the South. No proper study has yet been made of the southern fear of servile revolt.[31] Such a study would be fundamental to any adequate understanding of the reason why southerners suppressed all criticism of slavery and refused to permit abolitionists to cross the ” frontier.” The safety of the people who govern is always the supreme law. The southern states, however, in their resistance to northern anti-slavery propaganda went far beyond the demands of safeguarding the community from servile revolt.[32] They sought to segregate the minds of the white people from the virus of New England radicalism.

One of the most liberal-minded southerners, the historian Francis Lister Hawks, proposed a comprehensive plan of meeting the northern menace. His proposals were: (1) Let the South educate her sons at home, but let her make educational opportunities as good as those of the North; (2) let her use no violence against incendiaries and abolitionist emissaries she might detect within her borders; let them be dealt with according to the law; (3) let southerners discriminate between friends and enemies at the North; (4) let the South establish direct trade with Europe; (5) let her develop southern manufactures.[33] Some of the most violent southern partisans demanded the exclusion of northern text-books from the South. President William A. Smith, of RandolphMacon College, was a zealous propagandist for purging the text-books used in the South of sentiments or suggestions of abolition. ” The poison which our texts now contain,” he declared, ” must be distilled from them by the learned of the land.” The Southern commercial conventions and De Bow’s Review were also ardent advocates of the same policy.42 Bishop Leonidas Polk proposed, in 1856, to found the University of the South at Sewanee, Tennessee.At this institution the sons of southern planters should drink ” pure and invigorating draughts from unpolluted fountains,” and no longer patronize northern colleges. The University of Virginia could not qualify as the educational centre of the South, for it was not central enough nor was it ” suffciently cottonized.” The campaign to persuade southern youths to withdraw from northern colleges and enter colleges nearer home was condemned by some national-minded southerners, as John A. Gilmer, of North Carolina, who was later offered a cabinet post by Lincoln. In a speech at Philadelphia (1859) Gilmer spoke of those southerners who withdrew their children from northern schools on account of sectional prejudices as ” silly men.

The coming of northern immigrants into the South furnished another avenue by which northern radicalism could penetrate. In 1857, Eli Thayer, who had organized the Emigrant Aid Company for colonizing Kansas, conceived of a plan of settling Yankees on the worn-out lands of tidewater Virginia. He had already established a thriving little colony of northerners at Ceredo, in western Virginia.[34] But this plan of northern anti-slavery men invading the very heart of the Old Dominion aroused bitter defiance. The witty editor of the Richmond Examiner declared that Thayer proposed to descend upon Virginia with fragrant hordes of adventurers fresh from the onion patches of Connecticut and the codfisheries of the Bay State, and thereby make lower Virginia a paradise of onions, squashes, stringbeans, and ‘ liberty. [35]The other leading papers of Virginia, the Enquirer, the Whig, and the South, joined in the chorus denouncing ” the Vandal Invasion of Virginia.” [36] Distrust of northerners became intense after the criminal conspiracy of John Brown. Any suspicious-looking northerner who came into the South after that event was liable to be tarred and feathered. W. W. Holden, editor of the influential North Carolina Standard, urged (January 7, 1860) that a license tax should be imposed on all professional men educated at the North of at least one-half their fees, and that northerners entering the South to pursue their callings should be taxed in as drastic a fashion.

The need of combatting northern criticism led to the demand for a southern literature that would present southern civilization in the most favorable light. George Fitzhugh, of Port Caroline, Virginia, writing in De Bow’s Review, in 1857, declared the South could permit New England to make her shoes but not to write her books.[37] The South had been indoctrinated upon the rightfulness of slavery by a long line of polemical writers from the time of Thomas Dew to George Fitzhugh, and David Hundley. Their works, however, were not literature. The polished editor of the Southern Literary Messenger, John R. Thompson, issued a call for a sectional literature in an address of 1850.

It cannot be denied [he said] that there exists at this time a peculiar necessity for a home literature, and by this I mean a literature adapted to the institutions by which we find ourselves surrounded, and to the general framework of our society. Fanaticism in all of its forms, but worst of all in that fell shape of modern abolition which with impious tread, has dared to confront the presence of the Divine Majesty itself and mock at its revelation, stalks abroad through the land.[38]

In truth, though the South needed propaganda equivalent to the effectiveness of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the fervent appeals to produce a sectional literature fell on barren ground. [39]The example of Athens during the Age of Pericles producing immortal literature in a land of slavery was not to be repeated in the ante-bellum South — for more reasons than one.

Many complex factors explain the momentum of the antebellum South toward conservatism during the time that New England was becoming a centre of radicalism. D. R. Hundley, educated at the University of Virginia and Harvard, suggested an explanation in his Social Relations in Our Southern States: the southern planter lived out-of-doors, riding and hunting, and thus developed a sanity of outlook which made him foreign to the fanaticism of the North.[40] The predominantly rural condition of the South undoubtedly contributed to the resistance to northern radicalism. Yet this point should not be over-stressed, for in colonial days and during the revolutionary period, when the South was even more bucolic, the leaders of liberalism were southerners. In New England, the lyceum, which was a facile instrument for popularizing the reforms of the day, attained an immense vogue. The southern states, with few exceptions, did not share in this movement for adult education which encouraged enthusiasm for reform. The North itself was partly responsible for the reactionary attitude of the South. In attacking slavery with violence and want of intelligence, northern agitators aroused the intolerance of the South toward all reforms bearing the label ” northern.” And finally, the institution of slavery was itself a great weight in favor of conservatism. So firmly was it fixed in the fabric of southern society, that even idealistic southerners were opposed to any drastic disturbance of the status quo. Robert E. Lee expressed this feeling when he wrote in a letter of 1856 that the holding of slaves was an evil, but that their emancipation would sooner come from the mild and melting influence of time than from the storms and contests of fiery controversy.[41]

Only an atmosphere of good will and understanding could have led to an interchange of ideas and fruitful reforms between the North and the South. Both sections were parochial, New England as distressingly so as South Carolina or Alabama. Never having ventured beyond the Potomac, northerners entertained a distorted idea of the South and of the relations between the black man and the white man. Conversely, southern people seldom came face to face with æ Yankee. A small, fashionable set, it is true, made the yearly pilgrimage to Saratoga and Newport. Washington was also a meeting-ground of politicians from both sections, and their ladies. But the rank and file of southerners, having no contacts with northern people, held a stereotyped image of the Yankee that was nothing short of a caricature.[42] Because of this ignorance of conditions in the North, southerners made the fundamental mistake of exaggerating the numbers and importance of the northern radicals. [43]

An excellent antidote to the antagonism between a radical North and a conservative South would have been travel. The Virginia liberal, William Alexander Caruthers, realized the virtue of travel in cultivating inter-sectional comity and good will. ” Every southern [sic] should visit New-York,” he wrote in The Kentuckian in New-York. It would allay provincial prejudices, and calm excitement against his northern countrymen.” [44] The drawback to travel as a solvent of sectional antipathies is the fact that by no means all travellers move about with open minds. Even as capable an observer as Frederick Olmsted allowed his anti-slavery prejudices to color his view of the South. In contrast to Olmsted, who was fastidious about personal comfort, the genial Paulding had the right temperament for a visitor to the South. He would avoid stopping for the night at the neat, newly painted house, but he would seek out an old, rusty mansion. ” If I saw a broken pane stuffed with a petticoat,” he wrote, ” then I was sure of a welcome. [45]

The interchange of newspapers and magazines would also have contributed to an enlightened understanding. But influential northern newspapers, as the New York Tribune, or magazines like Harpeds and Putnam’s did not have a wide circulation in the southern states. During times of excitement they were indeed regarded as dangerous, incendiary publications. Thus the South tried to reduce its contacts with the North to a minimum and pursue a policy of splendid isolation. Resistance to northern radicalism, both fanatical and liberal, became an emotional imperative with its people.

****************************

[1] The Richmond Semi-Weekly Enquirer, December 23, 1859: Virginia State Library.

[2] The Richmond Daily Dispatch, December 23, 1859: Virginia State Library.

[3] Edward Ingle, Southern Side-Lights (New York, 1896) , 144.

[4] Arthur C. Cole, The Irrepressible Conflict, 1850—1865 (New York, 1934) , 52.

[5] W. G. Brownlow, Ought American Slavery to be Perpetuated: a debate between Brownlow and Prynne (Philadelphia, 1858) , 167.

[6] R. W. Emerson, Lectures and Biographical Sketches (Boston, 1887) ,

[7] -354.

[8] Governor Henry A. Wise, of Virginia, who had never stepped upon the soil of New England, wrote to his cousin in Boston, a son-in-law of Edward Everett: ” Why don’t he [Everett] and such as he in New England wield such pens against the wild “isms” of Massachusetts. Their moral influence would overthrow the monster. Boston seems to be a center of “isms,” Wise to Lieutenant Wise, September 11, 1855: Henry A. Wise MSS., Library of Congress.

[9] The Southern Literary Messenger, January, 1851: an article on ” The Night-Side of Nature.”

[10] The Southern Literary Messenger, July, 1853: an article on ” Spiritual Manifestations ‘ ibid., June 1854: an article on ” The Credulity of the Times.” 10 De Bow’s Review, XXIII (1857) .

[11] Vernon L. Parrington, The Romantic Revolution in America, 1800—1860 (New York, 1927) , 99—108; 317—434.

[12] The Richmond Enquirer, September 13, 1856.

[13] W. R. Waterman, Frances Wright (New York, 1924) , 92. For an account of the communistic societies in America of the period, see J. H. Noyes, History of American Socialisms (Philadelphia, 1870) , and W. A. Hinds, American Communities. Brief Sketches of Economy, Zoar, Bethel, Aurora, Amana, Icaria, the Shakers, Oneida, Wallingford, and the Brotherhood of the New Life (Oneida, New York, 1878) .

[14] See the angry review of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, in the Southern Literary Messenger (1852) , 631; also the review of the Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, ibid. (1853) , 322.

[15] William Hooper, Fifty Years Since: an address before the University of North Carolina (Raleigh, 1859) , 39: pamphlet in the library of the University of North Carolina. See, also, H. M. Jones, American and French Culture, 1750—1840 (Chapel Hill, 1927) , chapters x and Xl.

[16] Elisha Mitchell, ” Diary of a Geological Tour “: James SPrunt Historical Monographs, number 6, page 9.

[17] J. S. Buckingham, The Stave States of America (London, 1842) , 11 60—61.

[18] B. M. Palmer, The Life and Letters of James Henley Thornwell (Richmond, 1875) , 145—146.

[19] The Southern Literary Messenger (1835—1836) , 768.

[20] See a review of Nott’s Types of Mankind, by W. A. Cocke, in the Southern Literary Messenger (1854) , 661.

[21] University of North Carolina Magazine, September, 1860: library of the University of North Carolina.

[22] G. P. Merrill, The First One Hundred Years of American Geology (New Haven, 1924) , 157; see, also, Maurice Kelley, Additional Chapters on Thomas Cooper (Orono, Maine, 1930) , 18—24.

[23] The Southern Literary Messenger (1845) , 334.

[24] Diana Fontaine Corbin, Life of Matthew Fontaine Maury (London, 1888) , 160.

[25] Acts of the General Assembly and Ordinances of the Trustees for the Organization and Government of the University of North Carolina (Raleigh, 1852) , chapter VI, section 1: pamphlet in the library of the University of North Carolina.

[26] See the University of Virginia Literary Magazine, January, 1857, and

January, 1860: ” Religious Reforms.” Also, E. M. Coulter, College Life in the Old South (New York, 1928) : chapter Vlll, ” The Coming of Religion.” Occasionally a rebel would arise. A young Virginian wrote in 1850′. ” We find a secret silent abhorrence and dread in many minds of everything which partakes of a geological nature.” He protested against this fear of ” studying nature’s works “: Jefferson Monument Magazine (January, 1850) , 106: library of the University of Virginia.

[27] This isolated Unitarian church was in Louisiana. Of the 58 Swedenborgian churches only one was situated in the South; of the 17 spiritualist churches, not a single one existed on southern soil; and only 20 Universalist churches, out of the 664 in the country, were to be found in the southern states: Eighth Census of the United States, 1860; Mortality and Miscellaneous Statistics (Washington, 1866) , 500–501.

[28] Moncure Daniel Conway, Autobiography, Memoirs, and Experiences (Boston, 1904) , 1, 188.

[29] B. M. Palmer, The Life and Letters of James Henley Thornwett, ExPresident of the South Carolina College (Richmond, 1875) , 117–118.

[30] Lieber to Samuel B. Ruggles, December 13, 1855: Lieber MSS.; see, also, Thomas S. Perry, The Life and Letters of Francis Lieber (Boston, 1882) , 277— 285.

[31] W. S. Drewry, Southampton Insurrection (Washington, 1900) . See, also, U. B. Phillips, American Negro Slavery (New York, 1918) , chapter XXII.

[32] See Clement Eaton, ” The Freedom of the Press in the Upper South “:

Mississippi Valley Historical Review (March, 1932) .

[33] Francis Lister Hawks to David Swain, president of the University of

[34] Ceredo Crescent (October 24, 1857) : library of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.

[35] Richmond Examiner (April 3, 1857) : Virginia State Library.

[36] Richmond Enquirer (September 17, 1856) ; Examiner (May 22, 1857) ; New York Tribune (March 18, 1857) . The Norfolk Southern Argus, on the other hand, said, ” Let them come.” If the northern settlers did locate in Virginia, they would soon become converts to southern institutions: Southern Argus (April 22, 1857) .

[37] De Bow’s Review, XXIII.

[38] John R. Thompson, Address Before the Literary Society of Washington College, Lexington, Virginia (June 18, 1850) , 32.

[39] See Virginius Dabney, Liberalism in the South (Chapel Hill, 1932) , chapter Vil.

[40] D. R. Hundley, Social Relations in Our Southern States (New York, 1860) , 40—41.

[41] B. B. Munford, Virginia’s Attitude toward Slavery and Secession (New York, 1910) , 101.

[42] See U. B. Phillips, ” The Central Theme in Southern History “: American Historical Review (October, 1928) , 32, for a view of the abolitionist through southern eyes.

[43] Governor Wise revealed a typical southern point of view. ” We can’t be made to comprehend here how it is that the Sumners and Wilsons and Burlingames of Massachusetts should not be in a majority of the masses when they are so strong in the offices and in the influence of the North.” Wise to Lieutenant Wise, October 6, 1856: Wise MSS., Library of Congress.

[44] Parrington, The Romantic Revolution in America, 42.

[45] J. K. Paulding, Letters from the South (New York, 1817) , 11, 125.

Evolution is the theory explaining why 99.9 percent of all species ever to exist are extinct. But it can’t explain why the moon is 400 times smaller than the sun and the sun is 400 times farther away from the earth than the moon…and why we can see the corona of the sun in a solar eclipse…not that it couldn’t happen SOMEWHERE in the universe…it just can’t happen SOMEWHERE and be VISIBLE to man’s naked eye. Think about it.