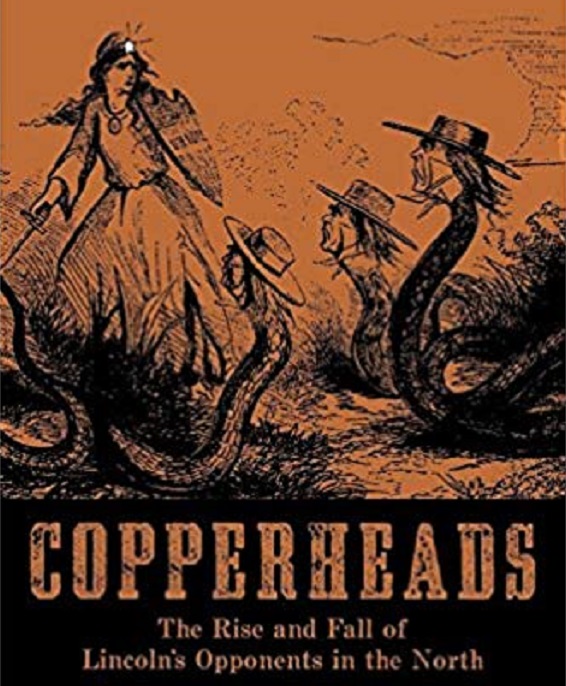

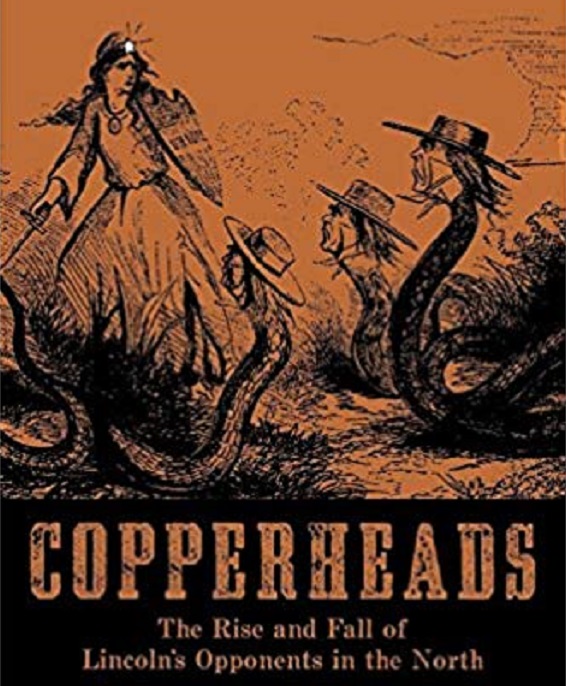

A review of Copperheads: The Rise and Fall of Lincoln’s Opponents in the North by Jennifer L. Weber (Oxford University Press, 2007).

They say a picture is worth a thousand words. In this case it is worth much more: 217 pages of them. The text comes wrapped in a handsome dust jacket, colored black and gold and featuring an arresting editorial cartoon from the War. In it, a stern-visaged but comely maiden stands her ground, brandishing a sword in one hand and a shield emblazoned with the motto “UNION” in the other; a white star shines from her forehead, symbolizing divinity. She is menaced by three poisonous copperhead snakes, whose human heads—gaunt-faced, long-haired, and topped by a flat-brimmed hat—are drawn to look like the stereotypical Southerner.

There is tension and danger but also the implication of resolution: the goddess of liberty shall lop off the heads of the traitorous foe—Northerners who favor peace.

A study of the Northern Peace Democrats is long overdue. Unfortunately, what we have here is a nationalistic melodrama masquerading as a work of scholarship. One hundred and forty years after the shooting stopped, historians still cannot resist keying their narration to the music of Julia Ward Howe.

One of the most important qualities of an historian is empathy, the ability to sympathize with the predicament and understand how the world appeared to different groups of people in the past. I cannot think of a better example than Daniel Walker Howe’s The Political Culture of the American Whigs (1979), which treats with sympathy and understanding, and without judgment, the rich and varied thought of the various groups that made up the party: the entrepreneurs, the evangelicals, the reformers, the conservatives, and the Southerners.

By contrast, Professor Jennifer Weber, who teaches at the University of Kansas, regards her subjects as reactionary reprobates who richly deserved the oblivion into which they were thrown after the War. Clement L. Vallandigham, the antiwar Ohio congressman and 1863 gubernatorial candidate, was an “ideologically driven outlaw,” whose “return to Ohio is nearly as amusing as his departure.” (Note the use of the present tense.) The man had been arrested in his home at midnight by federal soldiers, tried before a military commission, found guilty, and, by order of the president, banished to the Confederacy. Vallandigham later had to wear a disguise while sneaking across the U.S. border from Canada. She finds that very “amusing.”

Weber treats the Peace Democrats with relentless sarcasm and disrespect. One antiwar editor is described as “working himself into a rhetorical lather’ (i.e., foaming at the mouth), others are “apoplectic,” “blinkered by ideology,” or deluded by “utopian fantasies.” “The Copperheads lacked Lincoln’s understanding of the times,” and were deaf to his arguments, “powerful though they were.” Never does she do them the justice of fairly or accurately describing their thought.

She writes: “The Copperheads were so ideologically driven that they were blind to the threat that the war posed to the nation.” Actually, that was their greatest concern! What she meant to write was that they were blind to the threat that secession posed to the nation—but that’s not right either. For over twenty years, the Northern Democrats had warned their countrymen that political abolitionism would lead to the catastrophe of secession and civil war, and they were right. Republicans, on the other hand, dismissed these warnings and routinely derided the Democrats as “Union-Savers,” even after the election of 1860. Of course, Weber is unaware of such vital facts, but that does not keep James McPherson from anointing her, in his preface to the book, as the nation’s “foremost historian of the Copperheads.” How could McPherson withhold his encomium after reading that General McClellan was “nothing close to Lincoln’s equal in either moral fortitude or political prowess,” or that when Grant took command in the east “a new day had dawned over the Army of the Potomac”?

It is unsettling to study the War from the Republican perspective in a book that advertises itself as the opposite. Worst of all are the endless quotations from letters of soldiers who expressed the desire to go home and bayonet peace men. Weber thinks that the soldiers’ “bitterness toward the Copperheads was understandable” given what they were going through. I don’t think so at all (they should have been angry with the men who had sent them to the front); but it was predictable, given the brutalizing effects of a war waged not only against the organized armies but the civilian population of the South.

She lightly skips over the widespread violence committed against the mostly peaceful opposition—the mobbings, the beatings, the midnight arrests, the wrecking or closing down of antiwar newspapers—only to land on the conclusion that the victims were the chief perpetrators. To make her case, she resurrects the war-time scare tactics of the Republican Party, alleging that there existed Copperhead paramilitary organizations planning on freeing Confederate prisoners of war, raiding armories, and overthrowing the state governments of the Midwest. “It is nearly impossible to believe something was not afoot,” she writes; fears of a Copperhead-led insurrection were “not as fantastic as Klement and later historians have portrayed them.” She even refers to “Copperhead commanders,” a pure invention.

This was all fantasy, as was demonstrated conclusively by Frank Klement in his Dark Lanterns: Secret Political Societies, Conspiracies, and Treason Trials in the Civil War (1984). Weber disagrees, but offers no counter-evidence, no arguments as to how or where Klement got it wrong. There was violence against the draft, that’s true; but this was localized and spontaneous, not the result of central planning and control. There were Confederate agents sneaking about with cash, but none of their ambitious plots went anywhere. Confederate sympathizers did blow up steamboats on the Mississippi; Confederate raiders did rob three banks in St. Albans, Vermont; but these acts hardly amounted to an insurrection.

Remarkably, Weber avoids the most fundamental questions of the War— whether or not states could lawfully secede from the federal union, and whether or not the general government could lawfully invade them to force them back. The Democrats wrote and argued at great length about this, but Weber declares the opposite; “The Democrats never went into specifics” about the political nature of the Union, the meaning of states’ rights, or the constitutionality of secession. Having read the sources myself, I can testify that this is not true. But it was true of the Republicans, whose practice was to argue by assertion and denunciation; that is, not at all.

Weber makes some grave terminological errors. She writes: “Copperheads were antiwar Democrats” (true) who “most often called themselves conservatives” (false), while “‘Peace Democrats’ is a more neutral term that historians have chosen” (false). Then she confuses matters more by subtitling her book—“the rise and fall of Lincoln’s opponents in the North.” But Lincoln’s Northern opponents included the War Democrats, such as McClellan, whom she excludes from the Copperhead movement.

Let me clarify this.

The term Copperhead was applied indiscriminately both to those who opposed the War and those who opposed only the policies and methods by which it was carried on. The first were known as “Peace Democrats,” the second as “War Democrats;” both terms were in current usage. The term “conservative” was also in usage, but it was applied to the former Whigs who could not abide the Republican Party. The antiwar Democrats were conservative only with respect to race and the Constitution. On economics, politics, and civil liberties, they were liberal, democratic, and populistic. Witness the politics of these men before and after the War. To call them “conservative” is not only ahistorical; it seems an attempt to tar them with a word that remains a pejorative in the academy.

Weber includes a few quotes that offer a tantalizing taste of the intellectual depth and complexity of the opposition. Here is one from a New York editor.

In the name of liberty, the people have been arrested contrary to all law, and immured in military bastilles. In the name of the Constitution, the Constitution has been stricken down. In the name of the laws, the laws have been violated. In the name of freedom, the habeas corpus has been destroyed…. Under the pretence of saving the Union, these bloody-minded scoundrels have been doing their utmost to destroy it.

There are better books. Joanna D. Cowden’s “Heaven Will Frown on Such a Cause as This”: Six Democrats Who Opposed Lincoln’s War (2001) is a recent one, but the books by Wood Gray and Frank Klement remain unsurpassed.