This article originally appeared on LewRockwell.com.

For years those who advocated even a scholarly examination of secession were labeled “crackpots” and “fringe radicals” by the establishment. Secession had gone out of fashion with hoopskirts and mint juleps and had been “settled” by the gun in 1865. That argument worked well while the American empire seemed to be the glorious land of free people and a free economy. Just like Rome during the Pax Romana, why would anyone want to leave the immense majesty of the American peace? Much has changed in the last twenty years, and many Americans are coming to see secession as a remedy for the unfixable problems of the American regime, from bloated bureaucracy, high taxes, endless wars, broken healthcare and education systems, moral and ethical decline, and cheap money. And it is no longer the just the “fringe” advancing this position. Secession has gone mainstream.

Case in point is a new book by Douglas MacKinnon, The Secessionist States of America. MacKinnon would have been an unlikely candidate to write this book even ten years ago. He worked for the Reagan administration and is a popular guest on mainstream political television. MacKinnon is as mainstream as Sean Hannity, and yet unlike most talking heads on Fox News or CNN he was intellectually curious. This led to a dabbling in the theory of secession. MacKinnon eventually had what he describes as an uncomfortable revelation. What if America cannot be fixed from the inside? What if the next election or the next politician never made the situation better, but actually worse? What should Americans concerned with the out of control government in Washington D.C. do about it? His answer: secession.

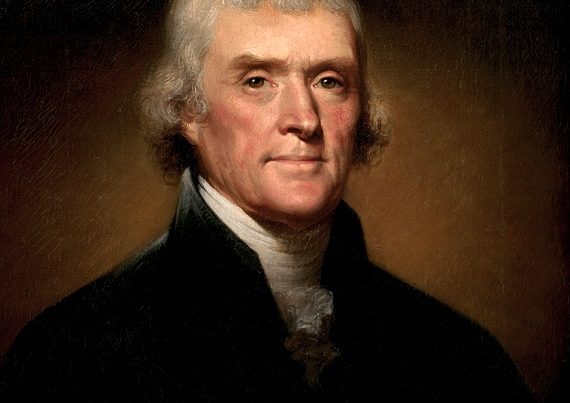

MacKinnon spends several chapters outlining the American principle of secession, from the American War for Independence to Lincoln’s illegal war against the South in 1861. He cites Americans from the founding era to the present, including yours truly here and here, who have argued and continue to argue that secession is both legal and the American political tradition. MacKinnon did his research, and his arguments are solid.

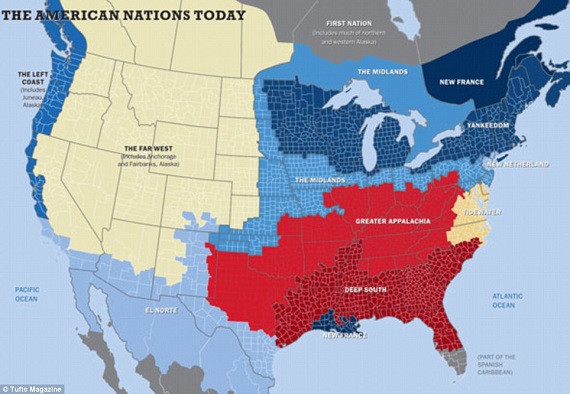

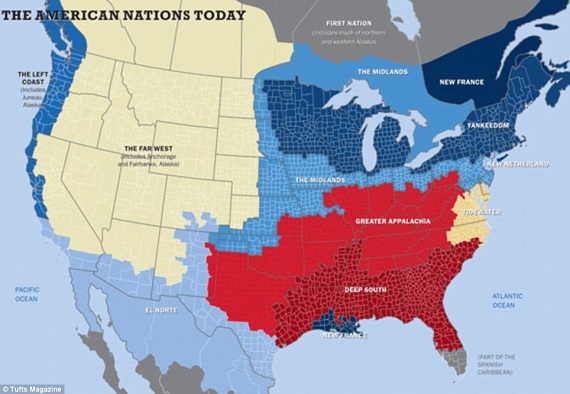

He then moves to a discussion on how modern secession would work. His approach here resembles two secessionist movements of the last one hundred years or so, one by black Americans following the War Between the States, the other a current movement in New Hampshire. The Exodus movement of the 1870s and 1880s led by Benjamin “Pap” Singleton centered on the goal of establishing black dominated “colonies” in Kansas, Colorado, Indiana, Missouri, and Illinois. Their central theme was economic, political, and social independence and freedom. This was an act of secession. Singleton and his followers did not believe they would ever be fully represented or protected in the United States, and these colonies would serve as culturally similar independent communities free from federal interference. If you can’t be free and can’t be safe, leave. The Free State Project in New Hampshire is an analogous plan. It calls for libertarians and small government minded people to move to New Hampshire to create free government and economic zones that foster free thinking and free government. The Free State Project has a smaller scope than Singleton’s Exodus, but both rely on individual acts of secession in a community setting. Neither are atomistic and recognize the importance of community and interpersonal relationships and culture. After all, good fences can make good neighbors.

MacKinnon suggests that people peacefully migrate to South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida in order to craft a “traditional values” country named “Reagan.” He selected these States because of their traditional culture and their resources, both man-made and natural. This would not be a place for everyone, obviously, but those who hold the same values would be free to have a republic of their own. How novel. MacKinnon consistently emphasizes that this would be a peaceful act of self-determination and suggests, quite pointedly, that any act of aggression against this new “nation” would be one of the greatest war crimes in history. World opinion would hold such an act of aggression in contempt.

MacKinnon’s book is important for two reasons. First, it is a clear example that Americans who would have been unwilling to advance a solution like secession are now listening to and even advancing the idea. Ron Paul recently wrote that the idea of secession should be open for discussion. Second, and more importantly, MacKinnon debunks the common notion that secession would be crushed by force if tried. Why? If enough Americans come to understand secession is an act of peace, not war, then why would secession be met by force? It does not have to be this way, and MacKinnon rightly attacks the Lincoln myth to emphasize his point. Lincoln could have chosen another path. It would have been the American thing to do.

Certainly the prospect of secession in 2014 is almost impossible. It would take years to do what MacKinnon suggests and even then it would require a more robust effort in educating the American public about the idea of peaceful self-determination. We have to undo one-hundred and fifty years of American propaganda on the issue. But MacKinnon’s book along with other developments around the world and the American response to them gives hope that secession may be a realistic option in the future.