Advance the flag of Dixie

For Dixie’s land we take our stand

To live or die for Dixie

And conquer peace for Dixie

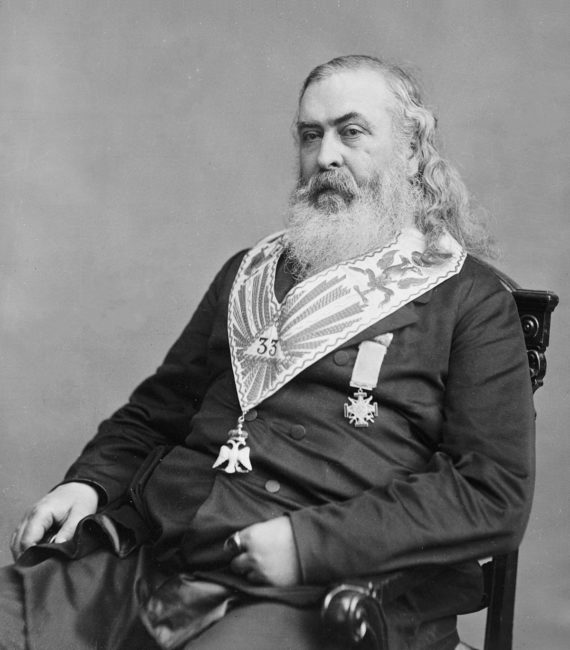

Anyone singing the above lyrics from the patriotic Confederate song of 1861, “Dixie to Arms,” would today, as with its earlier counterpart “Dixie,” be considered most politically incorrect and would probably ignite a firestorm of protest demonstrations and vitriolic tweets of condemnation. That 1861 song, however, was not, as one might now imagine, a polemic composed by some fire-eating Southern defender of slavery, but rather, like “Dixie,” it was written by a born and bred Northerner . . . a man many now consider to be America’s Plato, Albert Pike of Massachusetts. Like many in both the North and South at that time, Pike, while not an outright abolitionist, did believe slavery to be an evil that would ultimately be eliminated. Furthermore, even though he considered that secession did not violate the Constitution, he felt the North and South should settle their differences by mutual agreement, rather than by separation. However, as a strong advocate of state sovereignty and regional equality, Pike was also of the opinion that if such differences were irreconcilable, then secession was the only possible solution.

The Boston-born Pike was a celebrated author, jurist, poet and philosopher, as well as a futurist who, in 1871, predicted both World Wars and a potential third such conflict. He was educated at Harvard where he received an honorary master’s degree and was the head of his own school when, in 1831, he joined an expedition to New Mexico. Pike finally settled in Arkansas where he became a newspaper editor and an attorney who acted as a public defender of the rights of Native-Americans, and even argued cases on their behalf before the federal Supreme Court . . . once winning a three-million dollar judgement for a Choctaw tribe. After Arkansas seceded, Pike was first appointed as the Confederate Commissioner of the Indian Territory and then made a brigadier general in command of Indian troops, leading the tribal regiments during the 1862 Battle of Pea Ridge in Arkansas. Following the Confederate defeat, a clash with Major General Thomas C. Hindman over tactics led to Pike resigning his commission and returning to his law practice. In 1864, Pike was made a judge of the Arkansas Supreme Court and after his retirement, he mainly devoted his life to Freemasonry . . . ultimately becoming that order’s sovereign grand commander. In 1898, seven years after Pike’s death, the United States Congress authorized a statue to be erected in his honor, the only outdoor monument of a Confederate general in Washington, D. C. The eleven-foot bronze statue, created by the noted Italian sculptor Gaetano Trentanobe, now stands beside the Department of Labor. Needless to say, there currently are raucous cries and mass demonstrations to have this one hundred and twenty year-old memorial removed from public view.

Today’s conventional wisdom, as well as most of America’s history textbooks related to the War Between the States, portray those in the North as gallant crusaders against slavery, and those in the South as traitorous defenders of that institution. But what of men like New England’s Albert Pike and the tens of thousands of his fellow Northerners who elected to live and die in Dixie? While recounting the tales of all such individuals would require volumes, a simple look at the men from non-Confederate states or other countries who, like Pike, served the Confederacy as general officers should suffice to prove wrong all those who now seek to destroy monuments to the Confederacy, haul down its flags and point the finger of slavery’s shame at the South and her defenders. In all, there were approximately four hundred and twenty-five individuals who held the four ranks of general in the Confederate Army, with over twenty per cent of these coming from non-Confederate areas. While one might argue that the seventy generals who came from the border states of Kentucky, Maryland and Missouri should be eliminated from the equation because of their physical and philosophic proximity to the Confederacy, there remained the almost forty others from different regions. Of these, New York and Pennsylvania each supplied seven, followed by Ohio’s six, five from Massachusetts, three from New Jersey, two from Maine and one each from Connecticut, Indiana, Iowa and Rhode Island.

There were also at least seven Confederal generals from foreign countries . . . Patrick R. Cleburne, Joseph Finegan and William M. Browne from Ireland, Prince Camille A. J. M. de Polignac, Raleigh E. Colston and Victor J. B. Girardey from France and Collett Leventhorpe from England. Two of these, Cleburne and Prince de Polignac, were the only two to attain the rank of major general, with Prince de Polignac, or “Prince Polecat” as was affectionately called by his Southern troops, being the last living Confederate major general. Despite General de Polignac’s exotic background of having been a brigadier general in France and his father having been the principal minister to France’s King Charles the Tenth, the most famous of the two foreign major generals was Cleburne. Major General Cleburne was one of the South’s leading commanders, known as the “Stonewall Jackson of the West,” who, like Brigadier General Ortho F. Strahl of Ohio, was among the six Confederate generals killed during the 1864 Battle of Franklin in Tennessee. Incidentally, this battle took place under another officer who came from a non-Confederate state, General John B. Hood of Kentucky, the commander of the Army of Tennessee.

Besides Cleburne and Strahl, there were five other generals from the North or overseas who died for Dixie. Two were killed during 1862 Peninsula Campaign, Brigadier General Robert Hopkins of Ohio at Fair Oaks and Brigadier General Richard Griffith of Pennsylvania at Savage’s Station. The others were Brigadier General Clement H. Stevens of Connecticut who was killed during the Battle of Atlanta in 1864 and the two who died the same year in the defense of Richmond, Brigadier Generals Victor Girardey of France at Fussell’s Mill and Archibald Gracie III of New York at Petersburg. As a sidebar, General Gracie was brought up in a wealthy New York City family, with his grandfather’s home now being the official residence of the mayors of New York. In addition, Gracie’s son was one of the survivors from the “Titanic” and the general’s grave in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx area of New York City was among those vandalized during the current anti-Confederate craze.

In this group of Northerners, there were also two individuals who played pivotal parts in furthering the cause of the Confederacy. The first was the Confederate Army’s highest ranking officer, General Samuel Cooper from New Hackensack in Dutchess County, New York. General Cooper, who even outranked such historic figures as Generals Robert E. Lee and Joseph E. Johnston, served in overall military command as Adjutant General and Inspector General of all the Confederate Armies, and did much to bring order to what might have been a chaotic condition within the Confederate military. Prior to the War Between the States, General Cooper had been Adjutant General in the United States Army, as well as serving as interim Secretary of War between the administrations of Jefferson Davis and John B. Floyd in 1857. The second Northerner who played a vital role in the South’s war effort was Brigadier General Josiah Gorgas of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Gorgas had served at a number of United States arsenals throughout the country before the War and when he decided that the South had the right to secede, he resigned his commission as captain in the Union Army, went to Richmond and offered his services to the Confederate War Department where he was immediately commissioned a major and given the post as Chief of Ordinance for the Confederacy. Due to Gorgas’ almost unbelievable efforts in creating an arms and munitions industry in the South out of virtually nothing, as well as securing a continuous supply of war matériel from Europe, the Confederate military managed to be adequately armed throughout the War. These efforts were rewarded in 1864 when Gorgas was elevated to the rank of brigadier general.

In addition to Northerners who served as major cogs in the Southern war machine, there were others who also held important positions in the Confederacy. One of these was Major General Charles Clark from Lebanon, Ohio, who commanded a division at the 1862 Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee. After being severely wounded the following year during the Battle of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Clark became the Confederate governor of Mississippi. Another was Major General Martin Luther Smith from Danby in upstate New York whose family had originally come from Maine. Smith served as head of the Corps of Engineers for both General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and General Johnston’s Army of Tennessee and directed the building of defensive works at both Vicksburg and Mobile. A third was Major General Lunsford L. Lomax from Newport, Rhode Island, who had command of all the partisan cavalry units in Virginia, including the legendary Mosby’s Raiders. Another was Major General Franklin Gardner of New York City who served as as aide to General Braxton Bragg, and as chief of cavalry under General P. T. G. Beauregard at the Battle of Perryville in Kentucky. General Garner’s most important role, however, was that of commander during the forty-seven day siege of Port Hudson on the Mississippi River in 1863. Many historians consider Port Hudson to be one of the most outstanding defenses against a much larger enemy force. Lastly, there was perhaps the best-known but most reviled of all the Northerners who fought for the Confederacy, Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

After satisfactory service at various posts during the first year of the War, including Assistant Adjutant General and command of the Department of South Carolina and Georgia, Pemberton was promoted to lieutenant general and assigned to command the Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana which included the defense of the vital city of Vicksburg on the Mississippi River. Today, Pemberton is mainly remembered only as the Yankee who surrendered Vicksburg and his thirty thousand man army to General Grant on the Fourth of July.

Lastly, there were three generals from non-Confederate areas who offered a powerful argument against today’s mantra that the South was only fighting in defense of slavery. One of these was Major General Bushrod R. Johnson of Belmont County, Ohio. In 1863, while still a brigadier general, Johnson successfully led a division at the Battle of Chickamauga and later during the siege of Knoxville. The following year he stopped a Union advance towards Petersburg and was promoted to major general. Johnson, a Quaker, had initially broken with his religion’s tradition of conscientious objection by entering the U. S. Military Academy and serving in the Army. Following the Mexican War he resigned his commission and held positions as professor at the Western Military Institute in Kentucky and University of Nashville in Tennessee. Prior to moving to the South, however, Johnson had been an active abolitionist in Ohio, helping runaway slaves travel through the state along the famed Underground Railroad. There was also a Kentuckian, Brigadier General Humphrey Marshall, whose uncle was James G. Birney, one of America’s leading abolitionists. Birney was a member of the American Anti-Slavery Society in Ohio and the presidential candidate of the anti-slavery Liberty Party in 1840 and again in 1844. Then there was Major General Cleburne, the man from County Cork in Ireland who fought and died for the South. His stand was certainly not for slavery, which he detested, but because he and had found a welcome home and friends in Arkansas after a cold, anti-Irish reception in Ohio. During the third year of the War, General Cleburne saw that the South’s dwindling manpower would soon end its struggle for independence, and became one of the first major officers to propose that the Confederacy should offer manumission to any slave willing to fight for the South. There were other important figures, such as Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin, who agreed with the idea, but unfortunately the wisdom of Cleburne’s advice was not official heeded until just a month prior to General Lee’s surrender in April of 1865 . . . far too little . . . far too late. Cleburne had also offered some trenchant comments in his proposal when he wrote, “Satisfy the Negro that if he faithfully adheres to our standard during the war he shall receive his freedom and that of his race, and we (the Confederacy) change the race from a dreaded weakness to a position of strength.” He also had some prescient words in regard to today’s myth that the War was only waged to end slavery when he cited that “slavery is not all our enemies are fighting for. It is merely the pretense to establish sectional superiority and a more centralized form of government, and to deprive us of our rights and liberties.”

Amen to that!