Jefferson’s reference in Query XIV of Notes on the State of Virginia to male orangutans’ preference for black women is often cited as evidence of his unabashed racism and Jefferson’s sheer lack of criticality and his credulity. Jefferson writes:

Flowing hair, a more elegant symmetry of form, their own judgment in favour of the whites, declared by their preference of them, as uniformly as is the preference of the Oran-ootan for the black women of those of his own species.[i]

Annette Gordon-Reed, for instance, refers to that passage as evidence of Jefferson’s penchant for “seeing and expressing things in the extreme.” She says,

Of a piece with all of this was his habit of delving into books and finding (and believing) the sometimes outlandish stories told in them about things like the sexual preferences of orangutans in tropical jungles—an animal he knew nothing about, from a place he never visited.[ii]

Was Jefferson’s citation of Black women being pursued by orangutans a measure of his naiveté?

Rhys Isaac too criticizes Jefferson for writing of orangutans’ lust for black females, comparable for the lust of black men for white women.[iii]

So too does Paul Finkelman, who adds that Jefferson’s assertion that black men preferred white women was “empirically unsupportable,” as the reverse was “more likely the case, as he surely knew.”[iv] How does Finkelman know that the reverse is likely true is unclear? To what empirical data does he appeal? If none, then that addendum is gobbledygook. Finkelman is employing the same slanted pettifoggery of which he accuses Jefferson. In his case, the bias is obvious.

Such stories, of course, today seem outlandish, but they were not for the scientists of Jefferson’s day. For instance, the Scottish scientist and philosopher Lord Monboddo (aka, James Burnett), a progressivist apropos of thinking about the origins of species, considered the race of orangutans to be “a barbarous notion, which has not yet learned the use of speech.” Following the observations of Buffon, he continues:

He [the orangutan] is altogether man, both outside and inside, excepting some small variations, such as cannot makes a specific difference betwixt the two animals, and I am persuaded are less considerable than are to be found betwixt individuals that are undoubtedly of the human species.[v]

Thus, he excuses the Native Americans for dubbing him “Orang Outang” (“Wild Man”), since he resembles humans more than apes or baboons.[vi] He notes the existence of a human-like creature called “Pongo,” who resembles humans in all respects except being much taller. They like women and “frequently carry away young girls.”[vii] He cites also a type of orangutan, “Quimpezes,” which are from six to seven feet tall. “They carry away young negroe girls, and keep them for their pleasure.”[viii] He writes also of the capability of orangutans to acquire “some degree of civility and cultivation.”[ix] There is no racism here, but merely a limning of the observations of others, though Monboddo can be accused of credulity—viz., not vetting the reports of others.

Monboddo then emphasizes the alterations that occur with domestication of animals and brings to bear the example of dogs, which were bred and altered from some original prototype, perhaps the fox. He cites also the behavioral differences of wild and domesticated hogs. The former are solitary and fierce; the latter, social and tame.[x] The analogical argument is given to show that orangutans are humans in the most primitive state of nature.

Monboddo concludes his lengthy chapter:

I have dwelt thus long upon the Orang Outang, because, if I make him out to be a man, I prove, by fact as well as argument, this fundamental proposition, upon which my whole theory hangs, That language is not natural to man. And, secondly, I likewise prove that the natural state of man, such as I suppose it, is not a mere hypothesis, but a state which at present actually exists.[xi]

He does not say that his arguments and the facts leave no room for any conclusion other than the orangutan being human, but that he has “said enough to make the philosopher consider it as problematical, and a subject deserving to be inquired into.”[xii] Aside from not harboring racist sentiments, Monboddo privileges the African continent. If the human species did come from a state of nature, he sums, then

it must have been in such a country and climate as Africa, where they could live without art upon the natural fruits of the earth.

One sees here the origins of evolutionary biology and of the demise of Scala naturae.

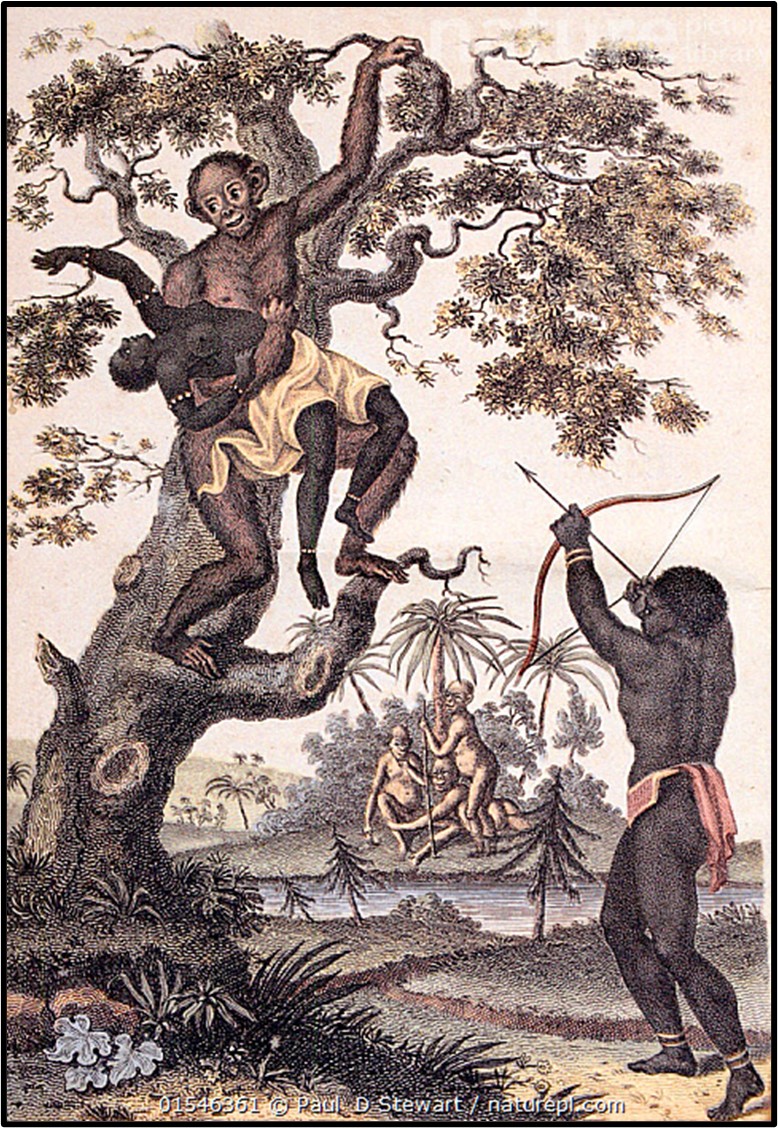

The frontispiece of one English translation of Linnaeus’ An Universal System of Natural History, Including the Natural History of Man: The Orang-outang; and Whole Tribe of Simia (picture below) depicts an orangutan snatching a black woman, away from her male partner. That, of course, would have created a goodly amount of shock value, and I am sure it was made for the frontispiece to do just that to sell the book.

What did the great Carl Linnaeus think of orangutans?

To understand deity’s ordering of nature, Linnaeus in his Systema Naturae classified living and growing things according to “genus,” and then created further levels of classifications until he came to three “kingdoms,” comprising animals, plants, and minerals. In the first edition of Systema Naturae (1758), Linnaeus broke down primates into four species: Homo, Simia, Lemur, and Vespertilio.

The category Simia included numerous species of primates—e.g., monkeys, orangutans, and apes—while Homo included only humans. Linnaeus was never comfortable with excluding humans from Simia, and he did so presumably only to eschew violent confrontation with religionists. He writes in a letter to Johann Georg Gmelin (25 Feb 1747):

I seek from you and from the whole world a generic difference between man and simian that follows from the principles of Natural History. I absolutely know of none. If only someone might tell me a single one! If I would have called man a simian or vice versa, I would have brought together all the theologians against me.[xiii]

The sentiment shows plainly how scientific attitudes are sometimes warped by political, here religious, pressures.

Linnaeus, following the four-humors theory of some Hippocratic physicians and Galen, divided the human species into four subspecies—five if one counts monsters as a subspecies. The criteria for differentiation were geographic location and color of skin. Under Homo diurnus, he lists:

- Homo rusus, cholericus, rectus (red man; bilious [angry], upright or honest; Americanus)

- Homo albus, sanguineus, torosus (white man; blooded [hopeful], muscular or fleshy; Europeus)

- Homo luridus, melancholicus, rigidus (yellow man; black-biled [depressed] man, inflexible or harsh; Asiaticus)

- Homo niger, phlegmaticus, laxus (black man; phlegmatic [stolid], lazy or relaxed; Afer)

- Homo monstrosus solo, vel arte

Under Homo nocturnus, he lists Ourang Outang, suggesting that the key difference between humans and orangutans is one of habit—humans being diurnal; orangutans, nocturnal.[xiv]

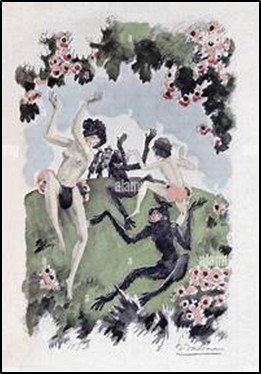

Finally, Voltaire in his well-received Candide writes of Candide and Cacambo coming across two naked women being chased and bitten on their buttocks by monkeys. Candide rescues the women by shooting the monkeys, only to find the women plunged into grief. The women were Oreillons—savages who eat their enemies and who inhabit an unknown country near Paraguay—and the monkeys were their lovers. Cacambo says:

Why should you think it so strange that in some countries there should be monkeys who obtain ladies’ favours? They are quarter men, as I am a quarter Spaniard (see picture below).[xv]

The castigations by Gordon-Reed, Isaac, and Finkelman of Jefferson’s sentiment on male Orangutans and black women is a coup manqué. That Jefferson delved into books and at times believed outlandish stories is obvious. We do the same today with the state of our science, which might be deemed sophomoric in the centuries to come. Once again, we find Jefferson at fault for keeping up with the science of his day—a science of which Jefferson’s critics today know little, if not nothing.

Enjoy the video below….

******************************************************

[i] Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, 138.

[ii] Annette Gordon-Reed, “The Resonance of Minds: Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the Republic of Letters,” The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Jefferson, ed. Frank Shuffleton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 187.

[iii] Rhys Isaac, “The First Monticello,” Jeffersonian Legacies (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993), 100.

[iv] Paul Finkelman, “Jefferson and Slavery: ‘Treason against the Hopes of the World,’” Jeffersonian Legacies (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993), 185.

[v] James Burnett, Of the Origin and Progress of Language, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1774), 270.

[v] James Burnett, Of the Origin and Progress of Language, 270.[vi] James Burnett, Of the Origin and Progress of Language, 271–72.

[vii] James Burnett, Of the Origin and Progress of Language, 275.

[viii] James Burnett, Of the Origin and Progress of Language, 277.

[ix] James Burnett, Of the Origin and Progress of Language, 278.

[x] James Burnett, Of the Origin and Progress of Language, 349–50.

[xi] James Burnett, Of the Origin and Progress of Language, 359.

[xii] James Burnett, Of the Origin and Progress of Language, 360–61. James Burnett, Of the Origin and Progress of Language, 359.

[xiii] From Justin E.H. Smith, “Natural History and the Speculative Sciences of Origins, The Routledge Companion to Eighteenth Century Philosophy, ed. Aaron Garnett (New York: Routledge, 2014), 723.

[xiv] In his book Dieta Naturalis, he said, “One should not vent one’s wrath on animals, Theology decree that man has a soul and that the animals are mere ‘automata mechanica,’ but I believe they would be better advised that animals have a soul and that the difference is of nobility.”

[xv] Jean François Marie Arouet de Voltaire, Candide (New York: The Literary Guild, 1929), 49.

Lord Monboddo sounds like a wild and crazy fella.

I hear that he had a chimp for a wife!