As a writer of some accomplishment—over 70 published books and several hundred essays—my success in writing is due to my deep love of writing. Most of the scholars that I know have told me either that they find writing painful or at least unpleasant. That is not the case with me. There are times, and they are not infrequent despite my age, when my fingers seem to melt into my keyboard. Then the scenario is not of a man expressing his thoughts on to a computer screen by tapping his fingers on to a keyboard, but rather of a man and of a computer that have forged a special, unitary relationship—what jocks call zoning.

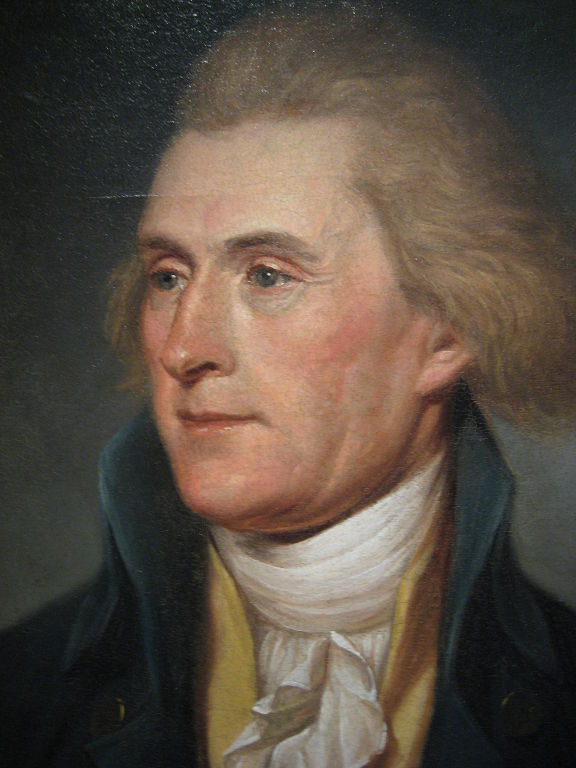

Much of my respect for and love of Thomas Jefferson is because I recognize that he is a fellow graphophile—one who really loves to write—and an accomplished wordsmith—one who knows how to put together words (e.g., craft elegant and clear sentences). Having at some point in life studied not only English, but also Ancient Greek, Latin, Modern Greek, German, French, and (now) Ukrainian, I have developed a large appreciation for the grammars of various languages, for the idiosyncratic usage of languages (example: the Greek word entoxei, meaning “fine” or “okay,” but acquiring the meaning of “keep babbling on” when one draws out the word), and for the art of crafting effective sentences, paragraphs, essays, and books in those languages to suit different purposes.

And so, much of my enjoyment of studying Jefferson is not only enjoyment of what he has to say—he knows so much about so many things!—but also enjoyment of how he writes. His letters are predominantly businesslike, and that is because most were for the sake of business, but they show an uncanny capacity to accommodate the interests and level of intelligence of his correspondents—what others call chameleonism and duplicity—but what I take to be Jefferson’s genuineness and high intelligence. While his letters to fellow republican James Madison tend toward dryness, his letters to the lovely and talented Italian coquette Maria Cosway are spirited and full of joie de vivre. His two inaugural addresses betray his national hopes and concerns in a manner that displays above-board concern for Americans everywhere. His Notes on the State of Virginia betray Jefferson’s enormous interests in preservation of history, science, morality, beauty and sublimity, and Virginian culture. Then there are his letters/essays on philology and neology (TJ to John Waldo, 16 Aug. 1813) as well as an essay on the rules for rhythm and sonority of English prosody (TJ to Chastellux, Oct. 1786), which demonstrate his love of Greek, Latin, and English.

In this essay, I cover the influence of the great critic of belletrism in Jefferson’s day, Hugh Blair, a figure given too little attention by scholars.

Fineness of speech and of writing—rhetoric and Belle Lettres—were important arts in Jefferson’s day, because in part speeches and literature were frequent topics of critical discussion in polite society. “We can hardly mingle in polite society without bearing some share in such discussions,” writes Rev. Hugh Blair (1718–1800) in his popular Lectures on Rhetoric and Bell Lettres. Taste through sound criticism is “one of the most improving employments of the understanding.” Blaire sums of the importance of good sense, beauty, solidity of phraseology, and unforced ornament in writing and speaking:

To apply the principles of good sense to composition and discourse; to examine what is beautiful, and why it is so; to employ ourselves in distinguishing accurately between the specious and the solid, between affected and natural ornament, must certainly improve us not a little in the most valuable part of all philosophy, the philosophy of human nature.

We learn self-understanding and improve morally, through study of the imagination.

Jefferson owned and enjoyed Blair’s Lectures on Rhetoric and Belle Lettres, published relatively late in Blair’s life (1783). That book would become Jefferson’s go-to book on rhetoric and belletrism, and so we can assume that Jefferson’s views on rhetoric and belletrism were very similar to Blair’s. On February 20, 1784, Jefferson writes to James Madison:

I shall take care to get Blair’s Lectures for you as soon as published.

Jefferson’s statement is in reply to a request from Madison (11 Feb. 1784) for a copy of the book, which Jefferson would thereafter heartily recommend to others for rhetoric.

Blair was a prolific writer, but Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres was perhaps Blair’s most significant work. It was a collection of 47 lectures, given while he was professor at University of Edinburgh. Though it is a collection of lectures, the book is no grab bag. It is remarkably structured—each lecture follows another in a sequacious manner—and marks him as the most significant early theorist on oratory and belles lettres.

The significance of the book lies in its comprehensiveness, in its structural integrity, and in its scope.

First, Blair draws from the early history of oratory—Demosthenes, Cicero, and Quintilian—as well as from contemporaries such as Edmund Burke, Joseph Addison, and Lord Kames.

Next, the 47 lectures are neatly and soundly structured and the manner of composition, elegant yet plain, is illustrative of points enumerated throughout the work.

Last, Blair focuses not merely on fineness of speaking, but also on fineness of writing—that is, not just oratory, but also on Belle Lettres—and he does so through examination not only of celebrated orations, but also of history and poetry. His book, he worries, is subject to the criticisms he makes concerning finely crafted writings.

Belles Lettres and criticism, says Blair of any writer or speaker, function “to embellish his mind, and to supply him with rational and useful entertainment.” He continues:

All that relates to beauty, harmony, grandeur, and elegance; all that can soothe the mind, gratify the fancy, or move the affections, belongs to their province.

Fineness if speaking and fine writing, in addition, lead to fineness of action.

They bring to light various springs of action, which, without their aid, might have passed unobserved; and which, though of a delicate nature, frequently exert a powerful influence on several departments of human life.

Yet rhetoric and belletrism also offer repose to a mind, strained by excessive activity—a point made by other aestheticians of his day—e.g., Lord Kames.

They strew flowers in the path of science; and while they keep the mind bent, in some degrees, and active, they relieve it at the same time from that more toilsome labour to which it must submit in the acquisition of necessary erudition, or the investigation of abstract truth.

Fineness of speech and writing, says Blair, is thought by many to be a sham art—a matter of pure ornament without substance.

When the arts of speech and writing are mentioned … a sort of art is immediately thought of, that is ostentatious and deceitful; the minute and trifling study of words alone; the pomp of expression; the studied fallacies of rhetoric; ornament substituted in the room of use.

He admits that rhetoric and belles lettres have been often misused “to the corruption, rather than to the improvement, of good taste and true eloquence.” That is a sentiment that has been noted since the time of Plato. As Jefferson was fond of noting, art can be overdone.

Blair continues with his modus operandi:

It is equally possible to apply the principles of reason and good sense to this art, as to any other that is cultivated among men. If the following Lectures have any merit, it will consist in an endeavour to substitute the application of these principles in the place of artificial and scholastic rhetoric; in an endeavour to explode false ornament, to direct attention more towards substance than show, to recommend good sense as the foundation of all good composition, and simplicity as essential to all true ornament.

One aspiring to excellence in speaking and writing, for Blair, must have large acquaintancy with the other fine arts—even the sciences.

The orator ought to be an accomplished scholar, and conversant in every part of learning.

There can be no art, “rich or splendid in expression,” but empty of thought. Grace cannot compensate for want of matter. Thus, beauty of expression, without meaning, is gibberish. That is in contrast to the tendency today of scholarly specialization. In Jefferson’s day, expertise in one subject entailed some degree of expertise in all subjects. Jefferson himself, when he undertook the study of law, studied any subject—e.g., math, music, literature, ethics, physics, languages, and religion—that could be of any significance in advancing the affairs of men.

The aims of fineness in speaking and writing are perspicuity, agreeableness, purity, grace, and strength. Yet conformance to rules of right speaking and writing is insufficient for right speaking and writing. There are also “private application and study,” as rules alone cannot inspire genius, but they can direct and assist it. In sum, rules must not only be applied, they must also be mastered, internalized. Rules cannot remedy barrenness; but they may correct redundancy. Rules point out proper models for imitation. Rules bring into view the beauty that ought to be examined, and the imperfections that ought to be avoided. Consequently, while rules might be insufficient for genius, they are sufficient for keeping an aspirant from being a fool—viz., they are necessary for genius.

What would not avail for the production of great excellencies, may at least serve to prevent the commission of considerable errors.

Blair lapses into an apology for the art of the fine arts: criticism. Study of rhetoric and Belles Lettres—that is, the art of criticism, is allied with “sound logic.” He elaborates:

The study of arranging and expressing our thoughts with propriety, teaches us to think, as well as to speak, accurately. … True criticism is a liberal and humane art. It is the offspring of good sense and refined taste. It aims at acquiring a just discernment of the real merit of authors. It promotes a lively relish of their beauties, while it preserves us from that blind and implicit veneration which would confound their beauties and faults in our esteem. It teaches us, in a word, to admire and to blame with judgment, and not to follow the crowd blindly.

Criticism, it follows, is necessary for individuation and individuation is necessary for a liberal democracy. Citizens cannot be part of a Jeffersonian republic if they cannot think for themselves. Groupthink is the enemy of liberal democracy.

Finally, Blair, certainly following Aristotle’s notions of dunamis (potentiality) and energeia (actuality), proffers a distinction between taste and genius.

Taste consists in the power of judging; genius, in the power of executing.

And so, genius is a “higher power of mind than taste,” for genius is in an actualization of taste.

Jefferson, I show in my book Jefferson on Taste and the Fine Arts, had a view of criticism that was like that of Blair. Given his appreciation for the genius of Blair, much liked by Jefferson for his own graphic artistry. It is likely that Jefferson’s artistry with his pen was due, in part, through study of Blair on belletrism.

In the video below, I offer some illustrations of Jefferson’s graphophilia—his love of writing….

Truly accurate about Jefferson, Professor! Not only did he write like no body’s business, he is even more wonderful to read. Inspiring.

Very kind of you, James. I am glad you enjoyed it. The video is different and gives examples of his style.