On Christmas Eve 1786, a mawkish Thomas Jefferson pens a letter (below, in toto) to Maria Cosway, a lovely Italian painter and musician, married by convenience to the eccentric and monkeylike Richard Cosway—a foppish macaroni.

Jefferson met the Cosways on August 6, 1786, when he and American artist John Trumbull met them by accident while Jefferson and Trumbull were admiring the stunning semi-circularly domed roof of Halle aux Blés (below), the new grain market in Paris. Jefferson was immediately smitten with the toothsome and talented young lady: a composer and performer of music and one of the foremost female sketchers and painters in Europe. Jefferson writes:

Yes, my dear Madam, I have received your three letters, and I am sure you must have thought hardly of me, when at the date of the last, you had not yet received one from me. But I had written two. The second, by the post, I hope you got about the beginning of this month: the first has been detained by the gentleman who was to have carried it. I suppose you will receive it with this.

I wish they had formed us like the birds of the air, able to fly where we please. I would have exchanged for this many of the boasted preeminencies of man. I was so unlucky when very young, as to read the history of Fortunatus. He had a cap of such virtues that when he put it on his head, and wished himself anywhere, he was there. I have been all my life sighing for this cap. Yet if I had it, I question if I should use it but once. I should wish myself with you, and not wish myself away again. En attendant the cap, I am always thinking of you. If I cannot be with you in reality, I will in imagination. But you say not a word of coming to Paris. Yet you were to come in the spring, and here is winter. It is time therefore you should be making your arrangements, packing your baggage &c. unless you really mean to disappoint us. If you do, I am determined not to suppose I am never to see you again. I will believe you intend to go to America, to draw the Natural bridge, the Peaks of Otter &c., that I shall meet you there, and visit with you all those grand scenes. I had rather be deceived, than live without hope. It is so sweet! It makes us ride so smoothly over the roughnesses of life. When clambering a mountain, we always hope the hill we are on is the last. But it is the next, and the next, and still the next. Think of me much, and warmly. Place me in your breast with those who you love most: and comfort me with your letters. Addio la mia cara ed amabile amica!

After finishing my letter, the gentleman who brought yours sent me a roll he had overlooked, which contained songs of your composition. I am sure they are charming, and I thank you for them. The first words which met my eye on opening them, are I fear, ominous. ‘Here I await it, and it never comes.’[1]

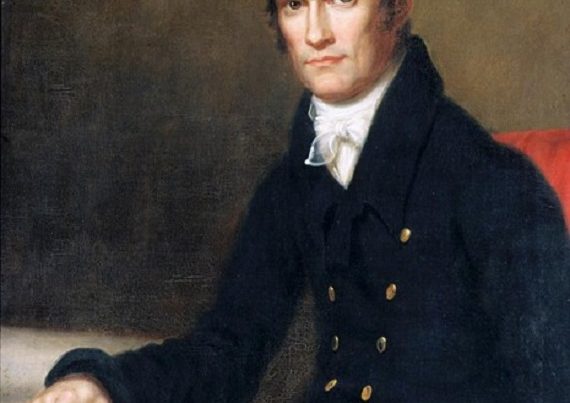

It would be a strange relationship—Jefferson’s intense feelings were unrequited—and Cosway, a seasoned coquette, would string along Jefferson as she had done with other persons of celebrity whose attention she captured. The image, below, is by the hands of husband Richard Cosway.

Why does Jefferson write to Cosway on Christmas Eve?

The answer, I suspect, is because she is Catholic and Christmas, though it was never fully celebrated as it is today till Charles Dickens wrote his masterpiece, A Christmas Carol, is dear to her. And so, on such a day, he thinks of her.

The letter shows that Jefferson pines to be with Cosway. After meeting in 1786, Jefferson and Cosway would spend many days together, until her departure with her husband for London in October 1786, after her husband had finished his portrait of the Duc d’Orléans, cousin of King Louis XVI, and the duc’s family—the reason for the Cosways being in Paris that year. Jefferson was so broken by her departure that he wrote the most singular letter of his life—called today his “Head and Heart” letter—a topic for another day.

Jefferson hopes, as the letter shows, to see again the Cosways in Paris in summer 1787. She would come, and without her husband, but she would take residence with the Polish princess Aleksandra Lubormirska—a residence far from Jefferson’s, at the western outskirts of Paris. The two would scarcely meet that year—Cosway was likely avoiding Jefferson because he came on too strong in his Head and Heart letter and that frightened her—and Jefferson’s feelings for her would subsequently chill. In 1787, Cosway would write seven letters to Jefferson; Jefferson, to her, only one.

Cosway would on May 4, 1790, have a baby, which she, with post-partem depression, would leave behind in London, as she sojourned for four years by herself in Italy. She was often seen with the singer Luigi Marchesi—the most celebrated singer of his day and a castrato—from 1791 to 1792. If their relationship was not sexual, it was certainly in other respects intimate. With Cosway gone, husband Richard would have his own flings, one, for instance, with fellow artist Mary Moser.

There would be a six-year drought, as it were, till Cosway resumes it in 1801 to congratulate Jefferson for becoming president. There would be another drought from 1805 to 1819, after which there would be seven more letters: only two by Jefferson. In four of Cosways’ letters, she expresses her wish to see once again Jefferson. In her final letter (24 Sept. 1824), she tells Jefferson—she now directs a school for young Catholic girls in Italy—that she is painting her map of the parts of the world on a wall in her school’s salon and she enjoins Jefferson to send to her some description of Monticello and his “Seminary” (University of Virginia.). Jefferson, sadly, never replies.

For more on Jefferson and Cosway, see the video below….

*******************

[1] “I here await it, and it never comes.”