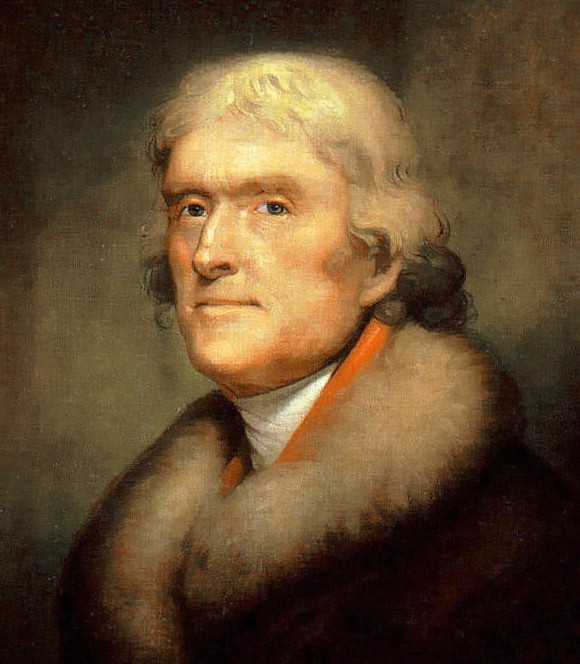

In a singular letter late in life to John Wayles Eppes (6 Nov. 1813), Thomas Jefferson describes the American Revolution as a “holy war.” He writes, “If ever there was a holy war, it was that which saved our liberties and gave us independance.” The letter rather mundanely concerns Jefferson’s abhorrence of banks and paper money. The letter I consider singular however on account of Jefferson calling the American Revolution a “holy war.”

What is a holy war?

It is a war that is so just that it has, by implication, the unqualified sanction of God. Yet Jefferson’s use of the term is metaphorical, for his deity is not one that intervenes in human causes. Nonetheless, Jefferson’s use of that metaphor moved me so that I devoted a book, The Disease of Liberty: Thomas Jefferson, History, and Liberty: A Philosophical Analysis, to the subject. His “liberty” was not merely an explanatory concept of historians that captures the climate of an epoch; it was hypostatized—a thing, a reality.

It is far too frequently presumed by Americans and scholars of American history that the Founding Fathers, in inciting their revolution with England, knew precisely what they were doing. We have only to consider their painstaking deliberations in the Continental Congress prior to deciding on war with England. Jefferson’s Summary View of the Rights of British America proffers numerous reasons for revolution. So too does his Declaration of Independence. We find those, and other, reasons iterated in the writings, speeches, and even cabals of George Washington, Patrick Henry, Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock, George Wythe, Alexander Hamilton, George Mason, John Adams, Samuel Chase, William Floyd, Richard Henry Lee, Caesar Rodney, and even Thomas Paine.

Just what occurred in the initial sessions of the Continental Congress is unclear, but what is clear is that the representatives agreed that King George and England’s Parliament were to be apprised of the Colonists’ grievances. There was also discussion concerning how the individual colonies, which had hitherto functioned independently, could put up a united front against England to bargain—the problem of confederation. Yet those deliberations—we have no first-hand account of what went on in the Congress—eventually morphed into discussion about whether, or not, to begin a war with Britain, when fighting began early in 1775 with the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

Why was there a revolution?

One answer is that the constant stream of immigrants from Europe, England especially and just prior to the revolution, made inevitable, or at least probable, the revolution. Colonial America was early on a melting pot for the unwanted: prostitutes, urchins, prisoners, the penurious, Scots, Welsh, and Irish, inter alii. The danger of the trip itself was incentive for any of the daring to eschew the risks. Yet over time, the perception for many was that the possible rewards were worth any risks. Writes Sir Thomas Miller to Henry Howard Suffolk, “In this part of the Kingdom transportation to America begins to lose every characteristic of punishment.” Persons with skills were beginning increasingly to begin life anew in the New World. England was beginning to lose some of “the most usefull of [its] people.

With the throng of not merely desperate, but increasingly useful, people to the New World and with its relatively limitless resources, Colonial America would soon rival and then exceed the mother country. The London Chronicle reports in 1773: “Every sensible person must foresee that our fellow subjects in America will, in less than half a century, form a state much more numerous and powerful than their mother-country. At this time, were they inclined to throw off their dependency, it would be very difficult for this kingdom to keep them in subjection.” The author imagines America in 50 years, when their number will have trebled from procreation without consideration of the increase from mass immigration. The argument in gist is in this rhetorical question: Why would a satellite state, which has become much more powerful than its mother country and which is situated a good distance from it, not seek independence from it? Continued dependence would mean advantaging the mother country to the detriment of the much stronger satellite state.

Gordon Wood in The Radicalism of the American Revolution writes: “There was little evidence of those social distinctions we often associate with revolution. … [There was] no mass poverty, no seething social discontent, no grinding oppression.” Americans were relatively prosperous and everyone was, in some sense, a commoner. Whatever distinctions that were between families and individuals were those of wealth, and though the wealthy in the 1700s were separating themselves from the non-wealthy, that was not a cause of anxiety. There was a general sense that any situation could be reversed: the wealthy could suffer a fall and the indigent could improve their situation through planning and toil.

There were no classes in Colonial America as there were in Europe. In Europe, because one was penurious, one worked; because one worked, one was penurious. In Colonial America, there was belief that work could lead to prosperity and a change of circumstances.

Though there were no classes in Colonial America, there were two sorts of persons: dependents (servants or slaves) and independents. An independent was a person whose will and property were his own; a dependent, whose will and property were not his own. John Adams sums in an address to the colonists of Massachusetts-Bay. “There are but two sorts of men in the world, freemen and slaves. The very definition of a freeman, is one who is bound by no law to which he has not consented.” Should Americans be unable to give or withhold to the acts of the British parliament, they would be slaves, not freemen.

The condition, adds Adams, is even worse. In England, both electors and elected have been softened by luxury, effeminacy, and venality. Both electors and elected are become “one mass of corruption.” Debt and taxes are large due to “extravagance, and want of wisdom.” To submit to subjection under such circumstances is not only submission to slavery, but also to “the most abject sort of slaves to the worst sort of masters.” The implication seems to be that it is the worst form of subjugation for thrifty, manly, and honest persons to submit to the extravagant, womanly, and dishonest.

Colonial Americans had, since colonizing the continent, been developing a strong sense of manly independence over the many decades. They had, of course, been first sent to North America without the patronage of the British government. They were “adventures”—in general, outcasts—sponsored by Virginia Company in 1607, with the goals of finding a route to the Orient, discovering gold, exporting raw goods, and even converting natives to Christianity.

Except for the presence of Native Americans, the land was pure wilderness, and the experience of such a mass of wilderness would have been overwhelming to a European, situated lifelong, for instance, in or near a large city like London or Paris. It was a new world, the New World, and to one in possession of industry, patience, and imagination, there was no limit to the uses to which the land could be put.

Ownership of land was proprietary more than functional. It was not so much what one could do with a parcel of land to turn a profit—though owning land and failure to work it was pointless—but instead it was just that one owned land that could be put to use. One’s identity was in large part determined by the land one owned, and that rang true especially throughout the South long after the American Revolution.

Colonial America, in short, was a place where a person without a name could make a name through industry and perseverance. Jefferson’s father, Peter Jefferson (1707–1757), was just such a self-made man. From unassuming parentage, Peter was not formally educated—“my father’s education had been quite neglected,” says Thomas Jefferson in his Autobiography—but did much to improve himself. With strong mind, sound judgment and eager after information,” Peter Jefferson read much and was chosen by Joshua Fry, professor of mathematics at College of William and Mary, to delineate with him the boundary between Virginia and North Carolina. With Fry, he made the first detailed map of Virginia. Peter Jefferson would become a justice of the peace in Goochland County, sheriff, county surveyor, and member of House of Burgesses. He married Jane Randolph (1721–1776), daughter of neighbor Isham Randolph, a prominent Virginian and member of the Planter Aristocracy of Virginia. The Randolphs were of the gentry of Scotland and England. Peter would acquire some 7,200 acres of land over his life. His Piedmont property in Albemarle County would be called Shadwell.

The charter of Virginia Company would be revoked, “by a mixture of law and force,” says Jefferson in Query XIII of Notes on the State of Virginia, and the land came under the yoke of King James in 1624, without Virginia Company receiving any recompense for their gross expenditure. By March 1651, Commissioners Richard Bennett, William Claiborne, and Edmond Curtis signed 16 articles “agreed on & concluded at James Cittie in Virginia for the surrendering and settling of that plantation under the obedience & government of the common wealth of England.” The first article stated that the people of Jamestown were declared subjects of the “Comon wealth of England,” and that that subjection is acknowledged to be “a voluntary act not forced nor constrained by a conquest upon the country, and that they shall have & enjoy such freedoms and priviledges as belong to the free borne people of England.” The Eighth Article states: “That Virginia shall be free from all taxes, customs & impositions whatsoever, & none to be imposed on them with out consent of the Grand assembly, And soe that neither ffortes nor castles bee erected or garrisons maintained without their consent.” As William Peden notes, the three commissioners were appointed by Cromwell for the sake of “reducing of Virginia and the inhabitants thereof to their due obedience to the commonwealth of England.”

Jefferson continues in Query XIII. Colonists assumed that they could participate in free trade, would be exempt from taxes not “of their own assembly,” and would be excluded from British military force.

None of those promises were kept, however. Jefferson sums abuses in the first 15 years of the reign of George III:

The colonies were taxed internally and externally; their essential interests sacrificed to individuals in Great-Britain; their legislatures suspended; charters annulled; trials by juries taken away; their persons subjected to transportation across the Atlantic, and to trial before foreign judicatories; their supplications for redress thought beneath answer; themselves published as cowards in the councils of their mother country and courts of Europe; armed troops sent among them to enforce submission to these violences; and actual hostilities commenced against them.

The abuses were consistent and without remorse. Colonists were fronted with “unconditional submission” or “resistance,” and they chose the latter.

The American Revolution was the revolution of the Enlightenment, which was a revolution against authority. The authorities targeted were chiefly Aristotle and the Church. There were new political, ethical/religious, and of course intellectual dimensions: Political ideals comprised governmental representatives by popular consent, human rights, institutionalization of liberty and equality, freedom of religion, and installation of governmental checks and balances, among other things. The most significant ethical/religious ideal was secularism. “Failure of religious doctrines concerning God and the afterlife to establish a stable foundation for ethics” turned many toward secular, naturalistic systems and deism. Along the same lines, many religions were naturalized insofar as enthusiasm, supernaturalism, and ecstasy were expunged.

That is why Jefferson considered the American Revolution as a holy war. All Patriots in some sense grasped that the American Revolution was a holy war, as it was a revolution unlike any other in human history. It was a revolution about what Latin moralists called honestum—moral worth. Fought on behalf of human liberty, it was an expression that human “destiny” was not fatally determined by God, as the Calvinists asserted, or by the law-governed movement of bodies in the universe, as Pierre-Simon Laplace asserted in Méchanique céleste, but determined by the thoughts and actions of individual human beings. Humans were organisms unique and, in the words of Thomas Jefferson in his last letter, not “born with saddles on their backs.

“The most significant ethical/religious ideal was secularism. “Failure of religious doctrines concerning God and the afterlife to establish a stable foundation for ethics” What? Can you elaborate a little bit on that, Mr. Holowchak? The quote you quoted, particularly.

Many were turning away in the Enlightenment from established sectarian religions and toward deism–the belief in God as creator of the cosmos without the metaphysical “trappings” of formal religions: belief in 3 gods in 1 god, miracles, a hereafter, &c.

Thank you for the reply. A sad commentary on their view(s). After all, they weren’t too far removed from the Reformation and the King James Bible. On the other hand, unfortunately, a vigorous recovery of Paul-line dispensational truth was still some years off, with Darby, Scofield, O’Hair, Baker, Stam, and others. Interesting article.

The central banks have loaded us to the gills with debt…and people keep on borrowing.

“Fought on behalf of human liberty, it was an expression that human “destiny” was not fatally determined by God, as the Calvinists asserted, or by the law-governed movement of bodies in the universe, as Pierre-Simon Laplace asserted in Méchanique céleste, but determined by the thoughts and actions of individual human beings.”

This site is really lucky to have the contributions of Dr. Holowchak and Mrs Protopapas, in particular. Both excellent thinkers and writers.

I think that because Calvinism is in particular subservient to mysticism, whatever emerged from it in the New England experiment soon sold itself in pursuit of whatever Cotton Mather or the local witchfinder general imposed on the general population.

It is notable that these supposed piously religious ‘elect’ jailed a helpless 5-year old girl in an adult prison, under accusation of being a witch, and not only did the local populous and jailers cooperate with this insanity, (probably because they knew they would be the next accused) but it was only when the Governors wife was accused of being a witch herself that anyone of the Calvinist ruling class became motivated to intervene.

Via John Adams – “On ne croit pas dans le Christianisme, mais on croit toutes les sottises possibles.”

Thank you. I had to look up “sottises.”

Mr. Holowchak, have you read, “God against the Revolution The Loyalist Case Against The American Revolution,” by Gregg L. Fraser? Or, “In God We Don’t Trust,” by David Bercot? Just wondering.

I have not. Thank you for those suggestions. My aim as analytic historian is not to praise TJ’s vision of liberty, but to expiscate it. In my book, The Disease of Liberty, I argue that TJ actually hypostatizes liberty. Hume’s view is much more sensible.

Thanks. I haven’t read those books either, but obviously I’m aware of them. I’m more interested reading in God Against The Revolution by Fraser because the other book, I think, shows that some Loyalist’s appealed to the Sermon on the Mount to defend their view. Dispensationally , the Sermon pertains to Israel, so I don’t think that was a good place in the scriptures for any Loyalist to appeal to. They needed to go to Paul’s epistles, if anywhere. Fraser’s book is expensive. I’m hoping for a discount some time.