In recent research, I accidentally happened upon this beautiful, touching story of a dying poet’s tribute to Robert E. Lee, and thought readers would find it interesting.

Like Lord Acton, the English poet Philip Stanhope Worsley was an admirer of the Confederacy and General Robert E. Lee. According to the Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900,

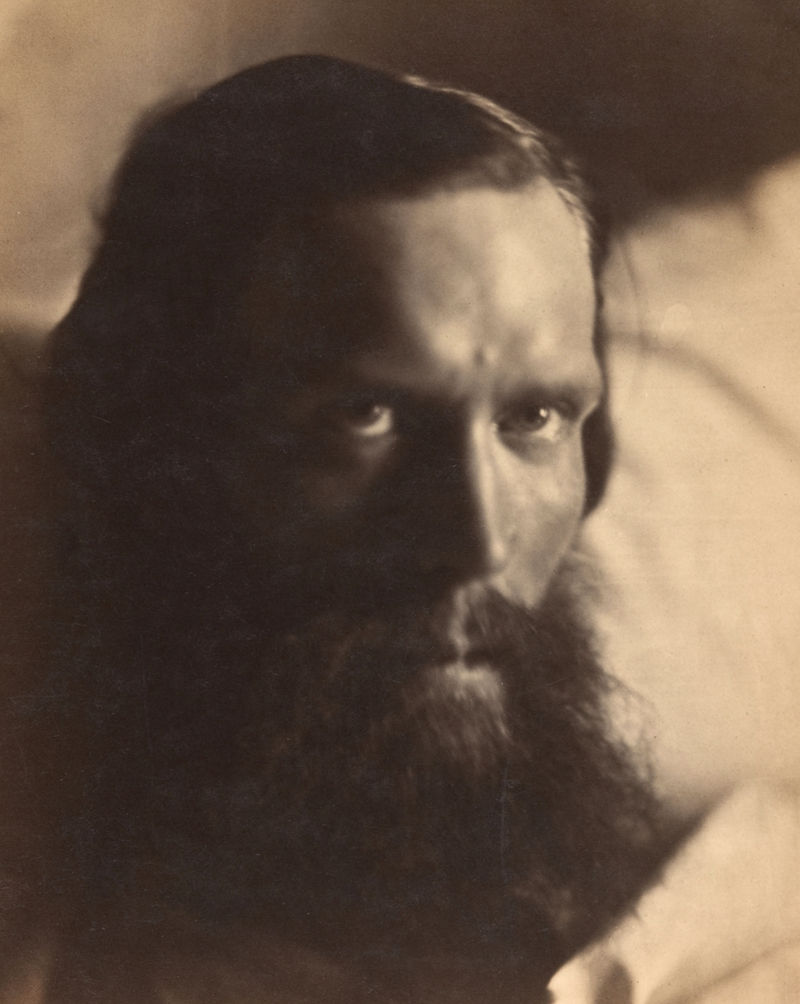

Worsley was born in Greenwich in 1835, and was admitted to a scholarship at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, in 1853, and graduated B.A. and M.A. in 1861. He gained the Newdigate prize (for his poem “The Temple of Janus”) in 1857, and became a fellow of his college in 1863. His health interfered with the pursuit of any profession, and he devoted himself chiefly to classical and poetical studies. His version of the Odyssey in Spenserian stanza was published in 1861, and his translation of the first twelve books of the Iliad in the same meter in 1865. On 8 May of the following year Worsley died unmarried at Freshwater after a long illness, terminating in consumption. His patience and cheerfulness under great suffering, and the beauty of his character, are pathetically extolled by Sarah Austin in a note to the Athenæum of 19 May 1866.

In 1904, Robert E. Lee, Jr. published Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee, in which he wrote of correspondence between General Lee’s nephew and Philip Stanhope Worsley, and the general’s gracious letters to the dying poet:

Among the many tokens of respect and admiration, love, and sympathy which my father received from all over the world, there was one that touched him deeply. It was a “Translation of Homer’s Iliad by Philip Stanhope Worsley, Fellow of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, England,” which the talented young poet and author sent him, through the General’s nephew, Mr. Edward Lee Childe, of Paris, a special friend of Mr. Worsley. I copy the latter’s letter to Mr. Childe, as it shows some of the motives influencing him in the dedication of his work:

“My Dear Friend: You will allow me in dedicating this work to you, to offer it at the same time as a poor yet not altogether unmeaning tribute of my reverence for your brave and illustrious uncle, General Lee. He is the hero, like Hector of the Iliad, of the most glorious cause for which men fight, and some of the grandest passages in the poem come to me with yet more affecting power when I remember his lofty character and undeserved misfortunes. The great names that your country has bequeathed from its four lurid years of national life as examples to mankind can never be forgotten, and among these none will be more honoured, while history endures, by all true hears, than that of your noble relative. I need not say more, for I know you must be aware how much I feel the honour of associating my work, however indirectly, with one whose goodness and genius are alike so admirable. Accept this token of my deepest sympathy and regard, and believe me,

“Ever most sincerely yours,

“P. S. Worsley.”

*********

On the fly-leaf of the volume he sent my father was written the following beautiful inscription:

“To General Lee,

The most stainless of living commanders

and, except in fortune, the greatest,

this volume is presented

with the writer’s earnest sympathy

and respectful admiration

and just beneath, by the same hand, the following beautiful verses:

“The grand old bard that never dies,

Receive him in our English tongue!

I send thee, but with weeping eyes,

The story that he sung.

“Thy Troy is fallen,—thy dear land

Is marred beneath the spoiler’s heel—

I cannot trust my trembling hand

To write the things I feel.

“Ah, realm of tears!—but let her bear

This blazon to the end of time:

No nation rose so white and fair,

None fell so pure of crime.

“The widow’s moan, the orphan’s wail,

Come round thee; but in truth be strong!

Eternal Right, though all else fail,

Can never be made Wrong.

“An Angel’s heart, an angel’s mouth,

Not Homer’s, could alone for me

Hymn well the great Confederate South—

Virginia first, and LEE.

“P. S. W.”

His letter of thanks, and the one which he wrote later, when he heard of the ill health of Mr. Worsley—both of which I give here—show very plainly how much he was pleased:

“Lexington, Virginia, February 10, 1866

“Mr. P. S. Worsley.

“My Dear Sir: I have received the copy of your translation of the Iliad which you so kindly presented to me. Its perusal has been my evening’s recreation, and I have never more enjoyed the beauty and grandeur of the poem than as recited by you. The translation is as truthful as powerful, and faithfully represents the imagery and rhythm of the bold original. The undeserved compliment in prose and verse, on the first leaves of the volume, I received as your tribute to the merit of my countrymen, who struggled for constitutional government.

“With great respect,

“Your obedient servant,

“R. E. Lee.”

************

“Lexington, Virginia, March 14, 1866

“My Dear Mr. Worsley: In a letter just received from my nephew, Mr. Childe, I regret to learn that, at his last accounts from you, you were greatly indisposed. So great is my interest in your welfare that I cannot refrain, even at the risk of intruding upon your sickroom, from expressing my sincere sympathy in your affliction. I trust, however, that ere this you have recovered and are again in perfect health. Like many of your tastes and pursuits, I fear you may confine yourself too closely to your reading. Less mental labour and more of the fresh air of Heaven might bring to you more comfort, and to your friends more enjoyment, even in the way in which you now delight them. Should a visit to this distracted country promise you any recreation, I hope I need not assure you how happy I should be to see you at Lexington. I can give you a quiet room, and careful nursing, and a horse that would delight to carry you over our beautiful mountains. I hope my letter informing you of the pleasure I derived from the perusal of your translation of the Iliad, in which I endeavoured to express my thanks for the great compliment you paid me in its dedication, has informed you of my high appreciation of the work.

“Wishing you every happiness in this world, and praying that eternal peace may be your portion in that to come, I am most truly, Your friend and servant,

“R. E. Lee.”

What wonderful correspondence in an era when men were truly men!

One cannot read Lee’s letters without being touched by the man’s eloquence and humility. The man’s kindness radiates from the page. And yet there are so-called “scholars” who accuse him of false humility, of disingenuity, of lecturing and moralizing! They know not the man! Such nonsense brings to mind Bree’s rebuke of Shasta: “Don’t display your ignorance.” Thank you for sharing this!

What a beautiful tribute! and such a gracious response from Lee. These are the ennobling things about people from the past that we need to hear often. They inspire us to imitate such values in the present.

I find it quite refreshing and interesting to read the letters of Victorian Christian gentlemen. Thank you for sharing this for I never knew it existed.

At the end of my book on Col. John Singleton Mosby, I made use of a phrase that Mosby used several times at the end of his life. As it, too, makes reference to the fall of Troy, I thought it would be appropriate as a comment on this article.

Mosby’s declaration of a “vision of a free and independent country” [made in his “farewell” to his command – vhp] does not invalidate his postwar efforts to foster reunion and reconciliation as the original vision had been lost, but it certainly does confirm that he did not reject that vision before it was lost. The former statement was from his heart, the latter from the very practical concern of preserving what was left of Virginia and the South from obliteration. But as his life changed and the end drew nearer, it is possible that his state of mind also changed. For that same avowed fidelity to the defense of a “lost cause” spoken of in 1906 was repeated not only in his last lectures given in 1910, but at the conclusion of his posthumously published Memoirs.

Few realize how extraordinary is John Mosby’s reiteration of this singular sentiment when considered in light of his long years working to achieve ultimate reconciliation and reunion between the North and the South. It is far more logical to assume that his final words to posterity would affirm the rectitude of the Union cause with an admission that the South’s defeat was for the good of the nation and the Southern people. After all, he had reiterated that latter sentiment many times after the war.

Yet in his final testament, John Mosby reaffirmed his fidelity to that “lost cause”: “If Troy could have been saved by this right hand, even by the same it would have been saved.” The significance of those nineteen words can be neither misunderstood nor misconstrued but should and must be considered an affirmation of his fidelity to that “free and independent nation” created by the people of the South in 1861—a nation that now existed only in memory. And while John Mosby did not reject the nation that had prevailed in that struggle, his final witness leaves little doubt that at the conclusion of a long and tempestuous life filled with honorable service to both nations, Colonel John Singleton Mosby truly wished that “The Cause” had not been lost.

I found this book on amazon because I wanted to own it but I also found it free online

https://leefamilyarchive.org/papers/books/recollections/index.html