This piece is taken from Brion McClanahan and Clyde Wilson Forgotten Conservatives in American History.

Two dates changed the course of American political history. On 13 September 1841, the Whigs expelled President John Tyler from their Party, outraged over his “betrayal” of what they considered true Whig political and economic principles. Shorty over two years later, on 28 February 1844, Abel P. Upshur, Tyler’s trusted Secretary of State and perhaps the best Constitutional scholar in the United States at the time, was killed in an accident on the U.S.S. Princeton. Both men personified American Whiggery and both are forgotten or maligned by the modern American historical profession. Historians generally consider Tyler’s presidency to be an abject failure while Upshur receives mention only in regard to his tragic death and his defense of slavery. Philosophically, however, their brand of States’ Rights Whiggery helped form the backbone of the American political tradition.

The Whig Party was initially a loose coalition of forces united by their opposition to Andrew Jackson. Historians give credit to New York newspaperman James Watson Webb for coming up with the name in 1834, but in reality “Whig” was used two years before that in South Carolina by advocates of nullification. The term, of course, implied that those who supported “King Andrew” and a powerful executive branch were “Tories.” This had a profound rhetorical effect as most Americans identified the term “Tory” with the British side of the American War for Independence. That was the point. Unfortunately, the men who later dominated the Whig Party and who kicked Tyler out in 1841, namely the former National Republicans led by Henry Clay, John Quincy Adams, and Daniel Webster, supported the same type of system they publicly railed against. They hijacked the name. Historians have for decades classified the Whig Party as the conservative antithesis to “Jacksonian democracy,” and it was in 1841 when Tyler assumed office after the death of William Henry Harrison. That Whig Party died when Tyler left office in 1845.

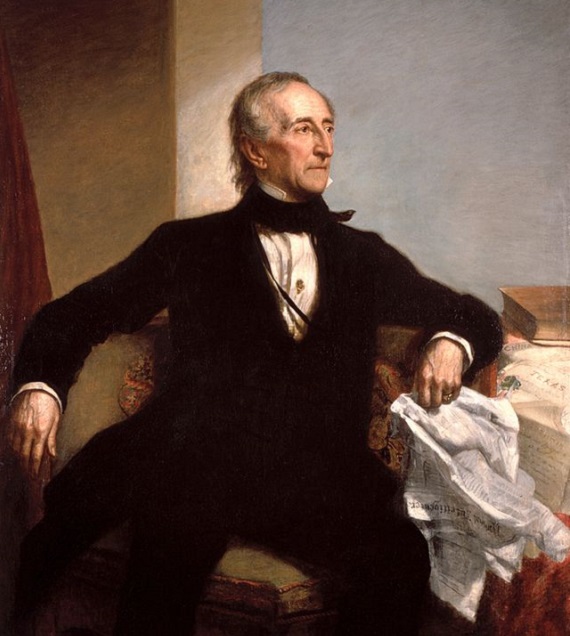

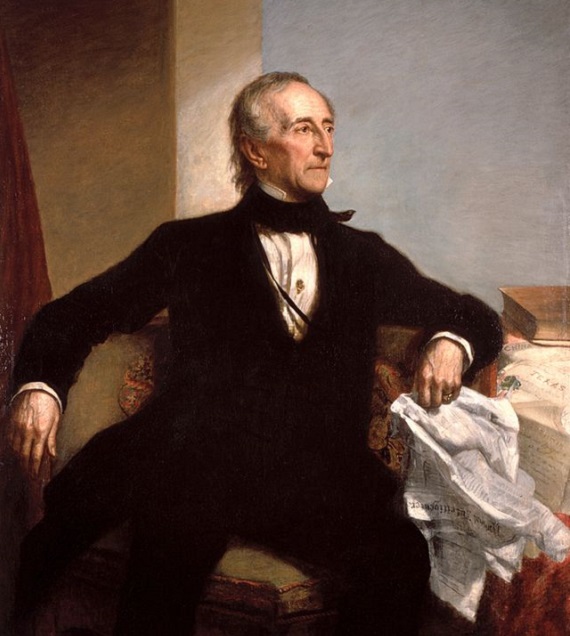

John Tyler, Jr., was reared in the American political tradition. Born on 29 March 1790 at his family plantation in Charles City County, Virginia, he was descended from a prominent Virginia family. His father, John Tyler, Sr., roomed with Thomas Jefferson at the College of William and Mary, was an anti-Constitution delegate to the Virginia Ratifying Convention of 1788, served in the Virginia House of Delegates and as Governor of Virginia, and later was appointed by James Madison to the federal court system. He was a well-known Jeffersonian and advocate of a limited central government.

Tyler, Jr., followed his father to the College of William and Mary where he was graduated at 17 and was admitted to the Virginia bar in 1809 at 19. He was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates at 21 and later to the United States House of Representatives in 1816 where he served three consecutive terms. He was appointed Governor of Virginia in 1825 and United States Senator from Virginia in 1827 where he served until 1836. After a brief retirement from public life, Tyler was nominated by the Whig Party for Vice-President in 1840. He was placed on the ticket in order to persuade Southern States’ Rights advocates to vote for the Whig Party in the election. It worked. The Whigs won the election in 1840 with Tyler later assuming office after the death of William Henry Harrison in 1841.

Critics called him “His Accidency,”and were frustrated with Tyler’s intractability on core “Whig” programs such as a national bank, federally funded internal improvements, and high tariffs. They should have expected no less. His political career was a testament to decentralization and States’ Rights, what he called the “principle” of “our Revolution,” and opposition to the Hamiltonian system. While in the Virginia House of Delegates in 1811, Tyler backed the censure of Virginia’s two Senators, Richard Brent and William Giles, because they voted to re-charter the Bank of the United States in complete disregard to their instructions from the State legislature. Tyler considered the Bank unconstitutional and insisted that by their action, Brent and Giles had ceased “to be the true and legitimate representatives of this State.”

Tyler consistently voted against nationalist legislation while serving in the United States House of Representatives. He opposed federally funded internal improvements—“Virginia,” he said, was not” in so poor a condition as to require a charitable donation from Congress”—fought against increases in Congressional salaries, argued that any surplus in the treasury should be used to reduce taxes and to pay off the national debt, and served on a committee charged with auditing the Second Bank of the United States. Tyler concluded after the audit that the Bank charter was “most shamefully perverted to the purposes of stock-jobbing and speculation.” His position was consistent with his Jeffersonian principles, and in a lengthy speech on the issue he declared that the Bank was “a system not to be supported by any correct principles of political economy…[and has] more to corrupt the morals of society than anything else.” Corruption of the principles of the Revolution was the key to his argument. “Our Republic can only be preserved by a strict adherence to virtue. It is our duty…to put down the first instance of detected corruption, and thereby to preserve ourselves from its contamination.” As for the debt, Tyler hoped that “The day…has passed, in which a national debt was esteemed a national blessing.”

By the time Tyler was appointed to the United States Senate, he was already regarded as a principled Jeffersonian, and he did nothing to damage his reputation as a United States Senator from Virginia. He continued to fight against federally funded internal improvements and crystalized his definition of Union. He considered the United States a republic of sovereign States and criticized those who regarded the United States as a singular nation. “I have no such word [national] in my political vocabulary,” he said in May 1830. “A nation of twenty-four nations is an idea which I cannot realize. A confederacy may embrace many nations; but by what process twenty-four can be converted into one, I am still to learn.”

But his greatest fight for the principles of Jeffersonianism was yet to come. As early as 1820, Tyler warned of the evils of protectionism. Protective tariffs, he argued, only enriched industrialists while impoverishing the agricultural class. The wisest course was to pursue a policy where foreign markets were encouraged to purchase both American agricultural and manufactured goods, thus boosting consuming power in the United States. This could only be accomplished through low, revenue only tariffs. His arguments and those of the other Jeffersonians fell on deaf ears. The 1828 tariff, called the “Tariff of Abominations” by South Carolina, and the 1832 tariff were the highest to that point in American history. Tyler opposed both, insisting that the end result would be the destruction of the agricultural interests of the United States. This, he said, would only antagonize the sections of the United States and would do little to produce the economic bounty the protectionists promised.

At the heart of each blow Tyler delivered to the Hamiltonian system was the insistence that Hamiltonianism, be it protective tariffs, federally funded internal improvements, or central banking, was nothing more than useless reform that perverted the ideals of the American federal republic and the principles of 1776. Historians have often tried to paint Jeffersonian political-economy as reactionary, and in particular a veiled defense of slavery, but Tyler never described it in those terms, nor did most Jeffersonians. He favored agriculture and the independence of the American people, neither of which could be maintained by high taxes, “stock jobbers” or centralization. This was American conservatism, pure and simple, and while it was best expressed by Southerners, it was by no means sectional.

Tyler’s break with the Democrats occurred during the nullification “crisis” of 1832-1833. He had always displayed an independent streak and had been a resolute opponent of unconstitutional executive action. Andrew Jackson’s response to nullification shook his faith in the Constitution and the Union. Tyler did not support nullification (he preferred secession), but when Jackson called for the use of force to collect the tariff, Tyler could not stand idly by and watch a sister State placed under the federal heel. “If South Carolina be put down,” he wrote in 1833, “then may each of the States yield all pretentions to sovereignty. We have a consolidated government, and a master will soon arise. This is inevitable. How idle to talk of preserving a republic for any length of time with an uncontrolled power over the military, exercised at pleasure by the President.” He cast the lone vote against the Force Bill in the Senate and made the only speech in opposition. Friends warned him against such a course, but Tyler’s sense of obligation to the Union of the Founders and his fear of a “consolidated military despotism” drove his actions in 1833.

In his long speech against the Force Bill, Tyler outlined his understanding of the Constitution. “The government was created by the States, is amenable by the States, is preserved by the States, and may be destroyed by the States….They may strike [the Federal government] out of existence by a word; demolish the Constitution and scatter its fragments to the winds.” He called on the examples of the American War for Independence and implored Congress heed those lessons. “It is an argument of pride to say that the government should not yield while South Carolina is showing a spirit of revolt. It was just such an argument that was used against the American colonies by the British government—an argument spoken against by Burke and Pitt….But it is a bad mode of settling disputes to make soldiers your ambassadors, and to point to the halter and the gallows as your ultimatum.”

Tyler’s reference to Burke and Pitt is important. Both men were loosely affiliated with the Whig faction in British politics, or those who opposed absolute monarchy, and both men, principally Burke, are regarded as intellectual heirs of modern conservatism, what Russell Kirk famously labeled the “Conservative Mind” in 1953. This “Conservative Mind” was best expressed by what would become the States’ Rights faction of the American Whig Party. Tyler classified his political ideology as Jeffersonianism. As he said in 1860, “I belonged, in short, to the old Jeffersonian party, from whose principles of constitutional construction I have never, in one single instance, departed.” This conservative adherence to the principles of 1776 determined his course as President of the United States.

In good Jeffersonian form, Tyler was at his planation when informed of the death of William Henry Harrison in April 1841. He hoped that the Vice-Presidency, a position regarded as little more than a ceremonial referee in the Senate, would give him a reprieve from politics. This was not to be the case. He immediately left for Washington and began preparations for his administration. His Whig counterparts in the cabinet thought Tyler should simply act as a rubber stamp for their nationalist economic program, but they should have understood Tyler’s ideological disposition. He had a clear track record.

After Tyler twice vetoed bills incorporating a third Bank of the United States, the entire cabinet—with the exception of Daniel Webster—resigned, a move orchestrated by Henry Clay, and then expelled him from the Party. Tyler also vetoed an internal improvements bill, a protective tariff bill, and nominated several States’ rights Whigs to cabinet positions after the nationalists jumped ship. In this way, Tyler placed a Jeffersonian stamp on the executive office. If the Whigs had been true to their name, Tyler’s actions would have been accepted without question. Clearly, the constitutionality of the Bank of the United States, a protective tariff, and federally funded internal improvements had been dubious at best. By vetoing this legislation, Tyler was following the parameters set forth by George Washington, i.e. veto legislation that is unconstitutional and let everything else pass. He was not abusing executive authority and as a man without a party could not be considered acting in a partisan spirit. He was simply being a consistent Jeffersonian. The nationalists couldn’t stand it.

If Tyler was the political brawn in the States’ rights faction of the Whig Party, then his Secretary of Navy and Secretary of State Abel P. Upshur had the sharpest legal mind of the group. Upshur was born in 1791 in Northampton County, VA. His father served in the War of 1812 and in the Virginia legislature as a Federalist. Upshur attended the College of New Jersey until his expulsion in 1807 for participating in a student rebellion against the faculty. He later enrolled at Yale but was never graduated. He studied law under William Wirt and served in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1812-1813 and again from 1825-1827. Along with Tyler, Upshur participated in the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1829-1830 and voted against plans to make the document more democratic. From 1826-1841, Upshur served on the Virginia supreme court. Like Tyler, Upshur consistently favored States’ rights and decentralization and was chosen for a cabinet position precisely because of his close ideological connections with the President.

The “loose interpretation” of the Constitution made famous by Alexander Hamilton found its way into the American common law through John Marshall and Joseph Story, a Marshall protégé, and was later championed by Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and Abraham Lincoln, all nationalist Whigs. Story, in 1833, published a seminal three volume work on the Constitution, entitled Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States. Story became both famous and wealthy from this publication and it was considered by many to be the standard interpretation of the Constitution. The Jeffersonians, however, thought it was nothing more than a thinly veiled codification of the nationalist interpretation of the document. Upshur took Story to task in 1840 and offered a counterweight to the nationalist vision of America, one that was truly Whiggish.

Upshur’s short treatise on the Constitution, titled A Brief Enquiry into the True Nature and Character of our Federal Government, did not receive the same notoriety as Story’s, nor did Upshur believe it would. He wrote in the Preface that he had little hope anyone would read his work or offer a “favorable reception, except from the very few who still cherish the principles which I have endeavored to re-establish.” Upshur claimed no originality, but because Story’s work had become so entrenched in American political-ideology, Upshur was original by offering an opinion that deviated from the nationalist fervor that swept the United States in 1840. He based his conclusions on “the authentic information from history, and from a train of reasoning, which will occur to every mind, on the facts which history discloses.” Rather than a technical legal “commentary,” Upshur’s work was more accurately a narrative of American constitutionalism from the American War for Independence forward. It was a work of history aimed at re-establishing the proper place of the States in American politics and most importantly rekindling the spirit and principles of 1776.

Upshur’s first order of business in his work was debunking the myth that Americans were “one people.” This formed the basis of the nationalist argument. If Americans were “one people,” than any piece of nationalist legislation, be it tariffs or federally funded internal improvements, could be justified on the grounds that it was best for the “nation” as a whole. Upshur contended that an American “nation” did not exist, and that by reading the preamble to the Constitution in such a way as to assume that the American “people” formed the government distorted the original federal republic. Upshur argued that Story’s “desire to make ‘the people of the United States’ into one consolidated nation is so strong and predominant, that it breaks forth, often uncalled for, in every part of his work.” It was often subtle, but without Story’s work, the nationalist version of American history may not have gained much traction in the late antebellum period.

Upshur wrote that “The unity contended for by the author no where appears, but is distinctly disaffirmed in every sentence….The people of the American colonies were, in no conceivable sense, ‘one people….’ The colonies had no common legislature, no common treasury, no common military power, no common judiciatory….Although they were all, alike, dependencies of the British crown, yet, even in the action of the parent country, in regard to them, they were recognized as separate and distinct.” All efforts in the colonial period to form a “general superintending government over them all” failed and each colony “was sovereign within its own territory; and to sum up all, in a single sentence, they had no direct political connexion with each other!”

Nationalists, Upshur wrote, would counter that while this may have been true in the colonial period, by the time of the American War for Independence, the “American people” rallied around a Union and formed a “national” government in 1774, if not legally but in fact. Upshur considered this to be imaginative construction. “Congress did not claim any legislative power whatever, nor could it have done so, consistently with the political relations which the colonies still acknowledged and desired to preserve. Its acts were in the form of resolutions and not in the form of laws; It recommended to its constituents whatever it believed to be for their advantage, but it commanded nothing. Each colony, and the people thereof, were at perfect liberty to act upon such recommendations or not, as they might think proper.”

Upshur and the other Jeffersonians understood that the “imaginative construction” of the nationalists was ultimately designed to reduce the power of the States, long a hedge against the evils of centralization. Upshur believed that the people of the States during the American War for Independence “never lost sight of the fact that they were citizens of separate colonies, and never, even impliedly, surrendered that character, or acknowledged a different allegiance.” Upshur was attempting to move the argument in a direction that favored decentralization. He did so by pointing out that even the Declaration of Independence, long considered by the nationalists as an action of the American “nation,” was in fact a “more public, though not a more solemn affirmation of what she [Virginia] had previously done [on 12 June 1776]; a pledge to the whole world that what she had resolved on in her separate charter, she would unite with the other colonies in performing. She could not declare herself free and independent more directly, in that form, than she had already done, by asserting her sovereign and irresponsible power, in throwing off her former government, and establishing a new one for herself.” This held true for the other States as well.

And this was just the tip of the spear. Upshur expertly shredded Story’s interpretation of the Preamble to the Constitution by pointing out that the original wording explicitly recognized the States and while it was later shortened to “We the People” late in the Philadelphia Convention of 1787, that did not alter its meaning. Moreover, the delegates to the Convention were appointed by the States so there was no question the Constitution was the work of the States, not the American people as a whole. It was ratified by the people of the States in convention and the States had a primary role in the document. “The Constitution is federative, in the power which framed it; federative in the power which adopted and ratified it; federative in the power which sustains and keeps it alive; federative in the power by which alone it can be altered or amended; and federative in the structure of all its departments.” He then asks “In what respect…can it be justly called a consolidated or national government?” Again, Upshur contends only through imaginative construction.

Upshur reserved his best arguments in support of State sovereignty. The question of sovereignty was paramount in antebellum America. Madison attempted to appease opponents of the Constitution in 1788 by coming up with the idea of dual sovereignty (the central government was supreme in its sphere and the States in theirs), but nationalists such as Story knew the score and rejected this idea. If they could reduce the power of the States, they would have unlimited control of federal resources and a monopoly on power. While Upshur believed nationalists were “dazzled” by this possibility, he saw only danger in a supreme central authority without limits. “Shall the agent be permitted to judge of the extent of his own powers, without reference to his constituent?” As the general government was created by the States, the States alone had the right to act as a final arbiter in any dispute. Both nullification and secession served as a final check on federal power but neither destroyed the Constitution as many nationalists suggested. In fact, Upshur defended nullification as a way to “prevent the Constitution from being violated by the general government,” in other words as a way to save the Constitution and the Union. Secession would have the same effect. “The act of secession does not break up the Constitution, except as to the seceding state.” To Upshur, nullification and secession were in essence a conservative response to ambitious and illegal reform.

As that Constitution was formed by sovereign states, they alone are authorized, whenever the question arises between them and their common government, to determine, in the last resort, what powers they intended to confer on it. This is an inseparable incident of sovereignty; a right which belongs to the states, simply because they have never surrendered it to any other power. But to render this right available for any good purpose, it is indispensably necessary to maintain the states in their proper position. If their people suffer them to sink into the insignificance of mere municipal corporations, it will be vain to invoke their protection against the gigantic power of the federal government. This is the point to which the vigilance of the people should be chiefly directed. Their highest interest is at home; their palladium is their own state governments. They ought to know that they can look nowhere else with perfect assurance of safety and protection. Let them then maintain those governments, not only in their rights, but in their dignity and influence.

Ultimately, Upshur contended that the Constitution, as interpreted by Story and other nationalists, would ruin liberty in America and would produce nothing more than monarchy. “If [Story’s] principles be correct, if ours be, indeed, and consolidated and not a federative system, I, at least, have no praises to bestow on it. Monarchy in form, open and acknowledged, is infinitely preferable to monarchy in disguise.” Fearfully, this monarchy would be controlled by the masses, by a tyranny of the majority that could oppress the minority population. Upshur considered majority rule acceptable at the State level, for States were generally homogenous. “But in a country so extensive as the United States, with great differences of character, interests, and pursuits, and with these differences, too, marked by geographical lines, a fair opportunity is afforded for the exercise of an oppressive tyranny, by the majority over the minority.”

Upshur prophetically saw the course of government in the United States. He surmised that the legislature, aware that it had self-imposed restraint, would soon destroy those restraints. Yet, the legislature would not long retain them.

In every age of the world, the few have found means to steal power from the many. But in our government, if it be indeed a consolidated one, such a result is absolutely inevitable. The powers which are expressly lodged in the executive, and the still greater powers which are assumed, because the Constitution does not expressly deny them, a patronage which has no limit, and acknowledges no responsibility, all these are quite enough to bring the legislature to the feet of the executive. Every new power, therefore, which is assumed by the federal government, does but add so much to the powers of the president. One by one, the powers of the other departments are swept away, or are wielded only at the will of the executive. This is not speculation; it is history; and those who have been so eager to increase the powers, and to diminish the responsibilities, of the federal government, may know, from their own experience, that they have labored only to aggrandize the executive department, and raise the president above the people. That officer is not, by the Constitution, and never was designed to be, any thing more than a simple executive of the laws; but the principle which consolidates all power in the federal government clothes him with royal authority, and subjects every right and every interest of the people to his will. The boasted balance, which is supposed to be found in the separation and independence of the departments, is proved, even by our own experience, apart from all reasoning, to afford no sufficient security against this accumulation of powers. It is to be feared that the reliance which we place on it may serve to quiet our apprehensions, and render us less vigilant, than we ought to be, of the progress, sly, yet sure, which a vicious and cunning president may make towards absolute power.

This is why Upshur, Tyler and other States’ rights advocates joined the Whig Party. They could see in Andrew Jackson the natural course of political power taking place in the United States. They were the pure expression of Whiggery. Once this faction was rendered powerless, the nationalist Whigs destroyed American Whiggery, for in the presidency of Abraham Lincoln, a partisan Whig for much of his political career, Upshur’s prophesies came to fruition. In this regard, the progressives of the twentieth century were correct that nationalism equaled reform. The Jeffersonian Whigs understood that and attempted to find a way to defeat it. The Democratic Party and the Whig Party, while appearing to be ideologically different, were, in fact, both the same nationalist party with differences only in the degree to which they supported centralization. States’ rights Jeffersonian Whiggary was an attempt to make a final stand against consolidation. They lost and by losing sealed the fate of the United States.