President Trump’s proposed ten-percent tariff on refined aluminum yields a teachable moment for Southern history students. Historical analysis of the industry reveals an echo of the Northern tariff policies that angered Southerners during much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries when the South was generally a raw materials exporter and feedstock supplier to Northern manufacturers. Tariffs during the era usually protected the Northern factories against competition from imports. Finished cotton goods made in New England, for example, benefitted from high tariff walls against imports of British finished goods. In contrast, a hypothetical raw cotton tariff could not benefit Southern cotton farmers because they were already the World’s low cost producers. In other words, a raw cotton tariff could not have blocked any imports since the imports were already negligible because of the South’s intrinsic cost advantage.

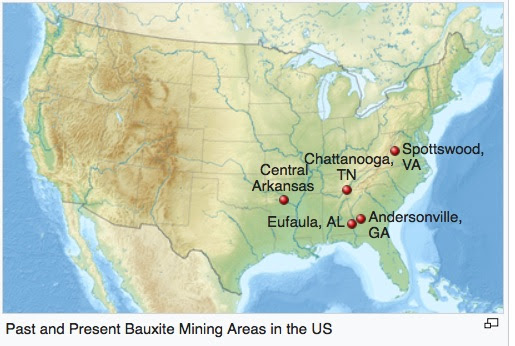

Just as textiles are made from cotton, aluminum is made from bauxite. As the map below shows, America’s bauxite deposits are exclusively in the South. Unlike cotton during the antebellum and postbellum eras, however, the South is not the World’s low cost producer of the ore. Cheaper ores are available elsewhere, most notably Jamaica. Therefore, Southern mines could have benefited from a tariff although the mines have presently almost faded away.

In contrast to the bauxite mines, America’s aluminum smelters are mostly in the North and West. They oppose bauxite tariffs because they want to keep their manufacturing costs as low as possible. But they applaud tariffs and quotas that protect them against finished goods imports. Protecting the domestic bauxite market, they reason, is contrary to the received wisdom of free trade economic theory, but protecting the domestic market for their finished goods . . . well, that’s different, see?

The only time aluminum smelters cared much about domestic bauxite producers was during World War II when imports were vulnerable to enemy submarine attack. The graph below illustrates the temporary boom to the domestic mines caused by the war. But after the war ended the smelters declined to support bauxite tariffs that would be high enough to prevent the economic extinction of the Southern mines. Even though domestic aluminum production is presently five times higher than during World War II peak, America’s bauxite production is down about ninety-eight percent from the same boom period.

The story of the domestic bauxite industry is only one example of the North’s opportunistic exploitation of Southern natural resources after the end of the Civil War. The former Confederacy was essentially transformed into an internal colony and remained so for nearly a century. Her residents, black and white, paid the price.