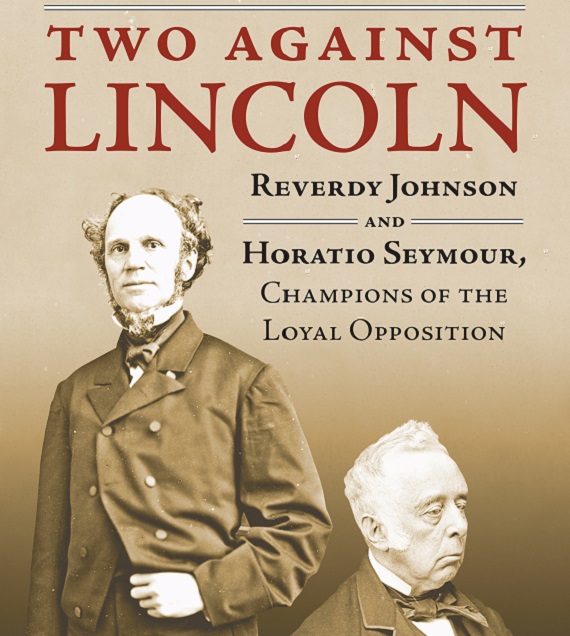

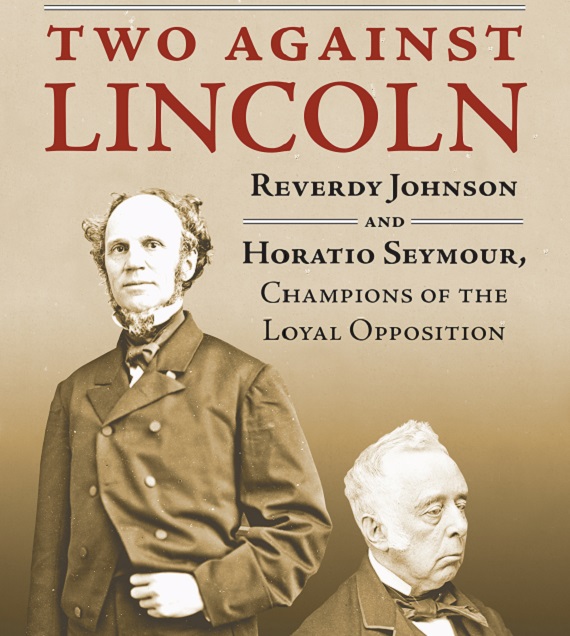

A review of Two Against Lincoln: Reverdy Johnson and Horatio Seymour, Champions of the Loyal Opposition (University Press of Kansas, 2017) by William C. Harris

In a speech before the Senate in 1863, James A. Bayard of Delaware stated that “The truth will out, ultimately…though they may be voted down by the majority of the hour, though they may not be known at first—the great truths will not triumph, with a little energy and a little perseverance.” Bayard had for two years relentlessly attacked the Lincoln administration for its legal gymnastics regarding the Constitution, and he believed that in the future, Americans would come to view the Lincoln administration as a watershed in a downhill slide to despotic government. Bayard later resigned from the Senate after taking Charles Sumner’s “Iron Clad Oath,” a vocal though defeated and marginalized critic of the Republican war effort.

Defeated and marginalized summarizes the entire collection of Lincoln opponents described as “Copperheads” by the Republican press. The reason is possibly tied both to Lincoln’s assassination in 1865 and the process of reconciliation after the War. Lincoln was martyred, his constitutional abuses chalked up to wartime necessities, and the burgeoning Lincolnian America solidified by the “Gilded Age.” But even long after the War, few historians spent much time studying Lincoln’s “fire in the rear” and those that did often regurgitated the partisan attacks leveled against them by the Republican Party both during the conflict and in the more militant phases of congressional reconstruction. For many Americans, men like Clement Vallandigham and illusions to the “Knights of the Golden Circle” conjured up images of “treason” and misguided opposition to a just cause. The Copperhead’s principled defense of “The Union as it was and the Constitution as it is” was left to the dustbin of American history, or worse described as the New York Times called it in 1864, “Copperhead charlatanry.”

Frank Klement resurrected the reputations of the Midwestern “Peace Democrats” in several monographs during the 1960s, but those volumes represented almost the entirety of scholarly research on the Copperheads for most of the twentieth century. Jennifer Weber revived interest in the Copperheads with her 2006 publication of Copperheads: The Rise and Fall of Lincoln’s Opponents in the North. While this tome has several flaws, notably the emphasis she places on race being the central theme of Copperhead opposition, it nevertheless forced the historical profession to reconsider Lincoln’s wartime opponents as a viable and principled collection of men.

William Harris’s Two Against Lincoln focuses on the actions of two “loyal opponents’ of the Lincoln administration: Reverdy Johnson of Maryland and Horatio Seymour of New York. Johnson is a little known United States Senator who sniped at the administration once taking his seat in 1863. His background as a former Whig and his familiarity with Lincoln adds to the story. Johnson spent much of his time in the concluding years of the War defending his fellow “Northern” conservatives against charges of treason by the Republican dominated Congress, attacking military interference at polling places across the North, but particularly in his home State, and in denouncing Lincoln for his “utter unfitness for the presidency.” He also gave one of the more important speeches in favor of the proposed amendment to abolish slavery, one that laid equal blame for the difficulty in ending slavery on virulent abolitionist of the North and staunch pro-slavery “fire-eaters” of the South.

Harris portrays Johnson as a man without a party and a moderate stuck in the middle of a nasty political war that spilled into Reconstruction. Johnson did not believe secession to be legal, nor did he think the Southern States had physically left the Union, but he bristled at the efforts of the radical Republicans to impose their political will on the South. He voted against Andrew Johnson’s impeachment and sealed the political deal that kept the president in office. Harris additionally argues that it was Reverdy Johnson’s work in defense of five men charged under the Ku Klux Klan acts in 1871 that established federal interpretation of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments for a generation. Harris concludes that:

Like many former Whigs in the border states and elsewhere, Johnson’s staunch Unionism was based on his belief in national progress and the greatness of American institutions. Although often opposed to Lincoln’s policies and conduct of the war, Johnson held a view similar to that of the president on America’s future and its transcendent purpose in fighting to prevent the destruction of the republic.

Thus to Harris, Johnson was neither a “Copperhead” nor a secessionist as contemporary critics claimed, but a loyal defender of the Constitution who differed with the Republicans and the Lincoln administration about war powers, the prosecution of the War, and the policies of Reconstruction, but not in the preservation of the “Union.”

As a former presidential nominee for the Democratic Party, Seymour has a higher historical profile than Johnson, but as Harris notes, like Johnson he is often little more than a footnote in the War narrative. That should not be so. Seymour was the wartime governor of New York and he worked tirelessly to restrain the wartime objectives of the Lincoln administration and the Republican Party. Seymour blamed the War on Northern fanaticism, the desire for New England to “meddle” in local affairs, and a press that buttressed their wild-eyed claims of a Southern “slave-power” conspiracy.

Harris describes Seymour as a principled conservative Democrat who like Johnson supported the War and never harbored any secessionist sentiment. Seymour sympathized with the Southern position in the 1850s and urged Northerners to adopt the Crittenden Compromise, but when Lincoln called for 75,000 troops to put down the “insurrection” in 1861, Seymour threw his efforts behind raising money and troops for the limited goal of the preservation of the Union. To Seymour and most Northern Democrats (as well as some Republicans including Lincoln), the War was not a righteous crusade to free the slaves but to save the Union. Seymour made that clear in his public pronouncements throughout the conflict.

Harris’s chapter on the post-bellum Seymour is a somber though somewhat biased review of Seymour’s political activities. Harris confidently asserts that the Republicans never intended to transform the Union, nor did Lincoln want to remake the executive branch. He describes Seymour’s speeches as shrill and filled with “typical hyperbole” that were intended to appeal to the paranoid element of the Northern electorate. His description of Republican reconstruction efforts implies that Seymour and the Democrats mischaracterized their motives. Seymour never wavered. He said after the War that “Time will set all that right.” Harris concludes “It never did.”

Though he has done a service to the reputations of both Johnson and Seymour, Harris’s conclusions still seem to maintain the traditional description of both men as little more than a perpetual nuisance for the Lincoln administration with paranoid and false predictions about the future of America. How can he make those claims? Because to Harris, Lincoln was a great politician capable of handling their dissent—something his successor was unable to do effectively—and who, “Fortunately for America,” chose to accept a “mighty destiny” to “save the Union.” Curiously, Harris believes that it has been “a long accepted view” that the War led to consolidation and executive abuse. If by long accepted he means never, then one can subscribe to his conclusion. Only recently has the Lincoln legacy come under sustained academic attack by a few hearty souls willing to challenge the now ingrained depiction of Lincoln as the quintessential American hero.

Though his book offers a fresh addition to the field of Northern dissent, Harris discounts his subjects’ prescient observations of American society and politics, both then and now. Harris’s affinity for Lincoln and for reading history in reverse produces conclusions that will forever maintain the tainted legacy of both Johnson and Seymour. They were wrong, and Lincoln was right. That is a subjective analysis.