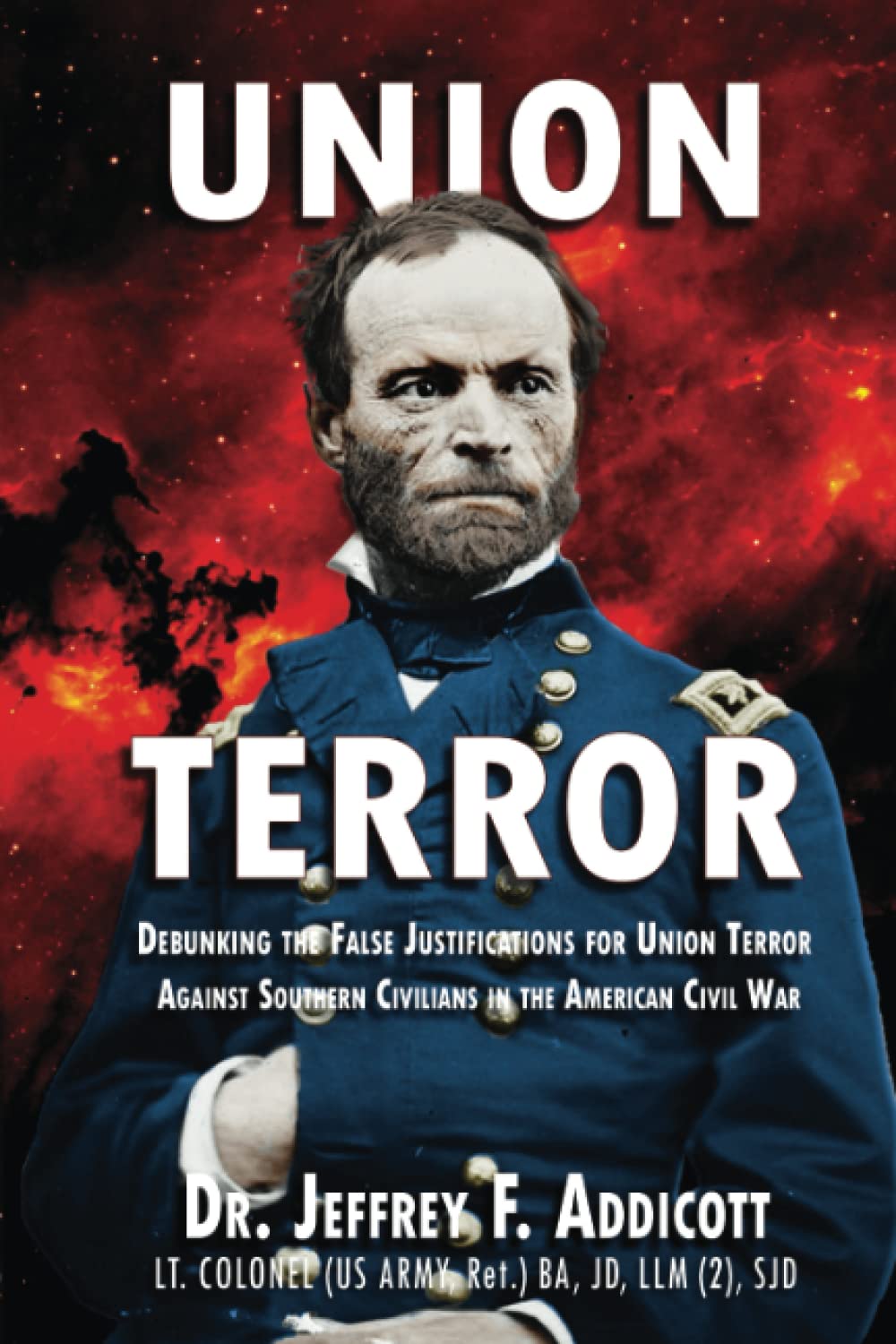

A review of Jeffrey Addicot, Union Terror: Debunking the False Justifications for Union Terror Against Southern Civilians in the American Civil War (Shotwell Publishing, 2023).

As an attorney and terrorism expert, Dr. Jeffrey Addicott’s new book, Union Terror, focuses on the legal standards of conduct by soldiers toward civilians applicable during the American Civil War. It cites incidents when Northern commanders and political leaders ignored those standards. Dr. Addicott is a twenty-year veteran of the United States Army. He spent much of his career as a senior legal advisor responsible for ensuring compliance within the laws of warfare. He was also a staff judge advocate within the Airborne Green Beret organization. Like Robert E. Lee his experience convinced him that ethical conduct and combat efficiency go hand-in-hand. “Lee,” writes Dr. Addicott, “did more to set the tone for ethical conduct on and off the battlefield than all the laws and codes put together ever could.”

The chief standard of lawful conduct that Dr. Addicott applies to the American Civil War belligerents is the Lieber Code. It set out rules of conduct during hostilities for Union soldiers. Even today, it remains the basis for most regulations of the laws of war for the United States. At the behest of President Abraham Lincoln, it was implemented via General Order 100 on April 24, 1863. That date was two years after the war began but also two years before it ended. Most of the violations occurred in the second half of the war when the Union armies were more set on destruction of the enemy than upon an honorable peace with former countrymen.

The impetus for the code was that the previous standard of the 1806 Articles of War did not contemplate a civil war. Since Lincoln did not recognize the Confederacy as nation, he did not want to apply internationally accepted standards to his soldiers. The Confederate government, of course, rejected the very idea that it was fighting a civil war, and continually pressed the United States, as well as neutral governments, to accord the Confederacy all the international rights of a sovereign nation. Lincoln, for example, regarded the crew of any ship that “shall molest a vessel of the United States” as pirates, who should not be treated as prisoners of war but instead, presumably, hanged as pirates.

Shortly after the Union Army adopted the Lieber Code, Confederate War Secretary James Seddon remarked that it was so flexible that “a military commander. . . may pursue a line of conduct in accordance with the principles of justice, faith, and honor, or he may justify conduct correspondent with the warfare of the barbarous hordes who overran the Roman Empire. . .”

One such contentious point is military necessity. During the 1864 “March to the Sea” from Atlanta to Savannah, Union General Sherman relied upon the term to justify liberal foraging of the countryside. According to Dr. Addicott, however, the interpretation should only apply in special circumstances where the army ran out of food due to emergencies caused by such things as extreme weather or unexpected enemy actions against depots.” However, such “uses of the military necessity doctrine were viewed as rare exceptions to the overarching general rule enshrined in the Lieber Code, which repeatedly emphasized protecting the private property and persons of all enemy noncombatants.” Sherman’s use of the doctrine “was nothing more than an ill-fitting cover slogan to shield him from criticism.”

According to Dr. Addicott, Lincoln knew all about the Union Army’s alleged violations during the second half of the war. “Thus, it is understandable that neither Sherman nor any of the other senior Union generals that conducted terror tactics in the 1864-65 timeframe ever faced disciplinary action, sanction, or even admonition from Washington, meaning that the Commander in Chief consciously and freely accepted these outrages.”

Readers interested in the conduct of the Union armies relative to a complex ethics code with 157 articles will find many instances where Addicott argues they violated the code. But readers should also be mindful of Secretary Seddon’s remark that the code is subject to interpretation. Given such flexibility the Holy Grail of a final word is elusive. For the present, it is in the hands of the cultural elite.

An analogous example is the current controversy over free speech. Political conservatives regard free speech as a near absolute right with few exceptions as, for example, shouting “Fire!” in a crowded theater. In contrast, the cultural elite believes that their free speech can be exercised by disrupting speakers with whom they disagree and by using cancel culture to deny their opponents access to the public square.

Finally, readers looking for a definitive narrative of Union Army wrongs against Southern civilians are reminded that the legal perspective is the common thread in this book. It also lacks an index which would help the casual reader discover incidents identified by geography and historical actors.

I finished reading this book yesterday and have re-ordered several more copies to give to my friends who are The War ‘buffs’ or re-enactors in many of the battles of The War!

Great no-nonsense book. Well worth a read and contemplation. You cannot be complacent after a read.

Yes, it’s excellent…contains a lot of unknown facts that spit in the face of the Union’s revisionist history. I’m buying a copy for a friend as well.

it still seems odd to me though that mere decades prior, onion states blather about seceding, you know, being soverign and getting away from a union….yet its such a mystery to the word-souper lincoln to call the csa pirates. helpful to have thousands of rascist, violent fresh euro-nationalists filling your ports, hungry and desiring a farm of their own.

Highly recommended: LINCOLN’S CODE: THE LAWS OF WAR IN AMERICAN HISTORY. The work won the Bancroft Prize, and is packed with archival research.