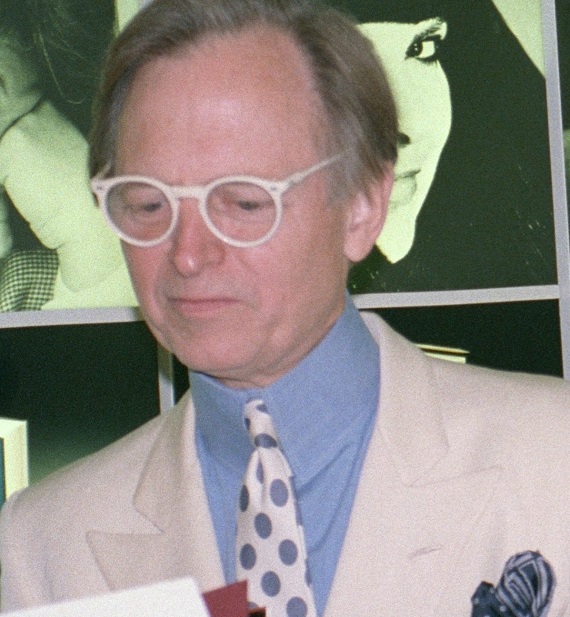

Tom Wolfe was one of the most insightful writers and novelists of the second half of the twentieth century. He was also a Washington & Lee graduate who sometimes championed politically incorrect viewpoints, a context in which he was ahead of his time. Today’s W & L faculty and administrators would do well to take note.

In 1970, he published two essays: Radical Chic and Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers. The first ridiculed a fund-raising soiree that composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein hosted at his Park Avenue apartment for the Black Panther Party. Wolfe peeled and roasted the attending whites for their absurd and righteous pretense. The second essay described how various San Francisco minority groups intimidated government program administrators (Flak Catchers) into giving them money. He showed how a combination of bureaucratic ineptitude and white guilt combined to release taxpayer money to group leaders who embezzled the anti-poverty funds for themselves.

But the best example foreshadowing increasingly prevalent race hustling is his 1987 novel, Bonfire of the Vanities. To be sure, the chief character is a philandering and perhaps over-generously paid Wall Street bond trader named Sherman McCoy. After picking up his mistress at Kennedy airport he takes a wrong turn off a bridge to Manhattan and ends up in the Bronx late at night. After a brief tour of the dysfunctional borough, he finds a ramp to a bridge connecting to Manhattan. While trying clear road debris blocking the ramp, he is menaced by two sinister black youths. His mistress gets behind the steering wheel and guns the car to rescue Sherman who jumps-in as the Mercedes passes by and simultaneously hits one of the blacks.

While hospitalized in a coma the youth becomes a cause célèbre for the black Reverend Reginald Bacon who uses his followers to stir-up community resentment with demonstrations. His purpose is to generate publicity to give a white lawyer—with whom he will share the winnings—an edge in a multi-million malpractice suit against the hospital. Given Al Sharpton’s weight and body-mass-index at the time, there’s little doubt that Reverend Bacon was a stand-in for him. During press interviews Bacon misrepresents the victim as an honor high school student intent on being the first in his family to get a college degree. Bacon’s increasingly large demonstrations pressure borough politicians to find and prosecute the driver. White guilt and fear of losing the next election control them. They become desperate to find the guilty driver or a culturally acceptable substitute, apparently even if not guilty.

The car is eventually traced to Sherman from a partial read of the license plate by the injured youth’s companion. Even though his mistress drove the hit-and-run car, she denies it when police question her. That leaves Sherman as the ideal villain within the racially charged atmosphere.

While Wolfe’s story does not excuse Sherman for his part in the crime, it also shows how Bacon’s race hustling and cowardly white politicians combined to corrupt justice. Twenty-five years ago, Wolfe’s novel showed that America was evolving into a culture wherein race-baiting and white guilt could be exploited in a progressively massive scale. One consequence is that Southern History has become merely a subset of Black History.

When he attributed the recent fatal beating of a black youth in Memphis by five black policemen to white supremacy Sharpton revealed that he has evolved into a caricature of Reverend Bacon and thereby a grotesque parody of himself.