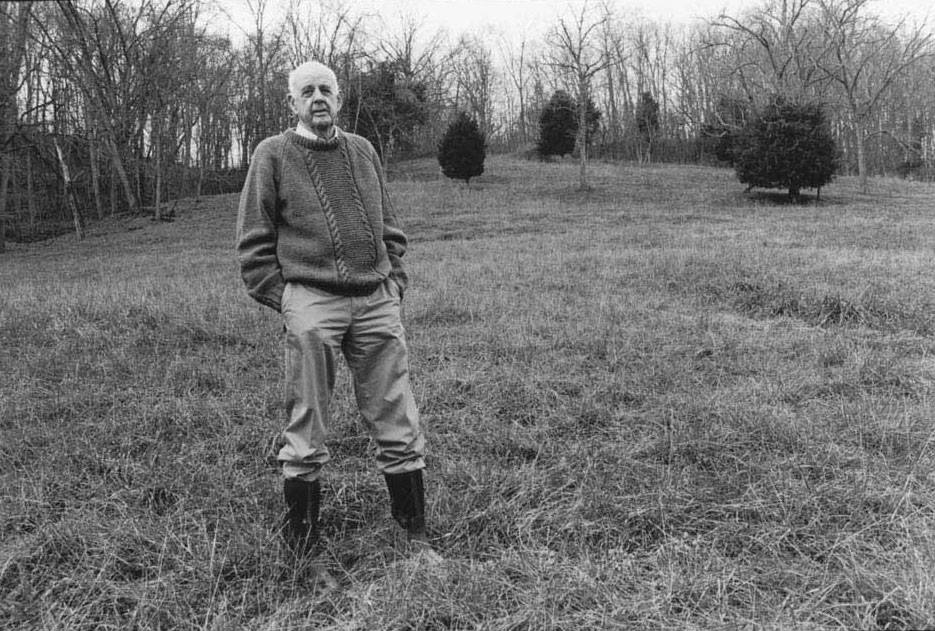

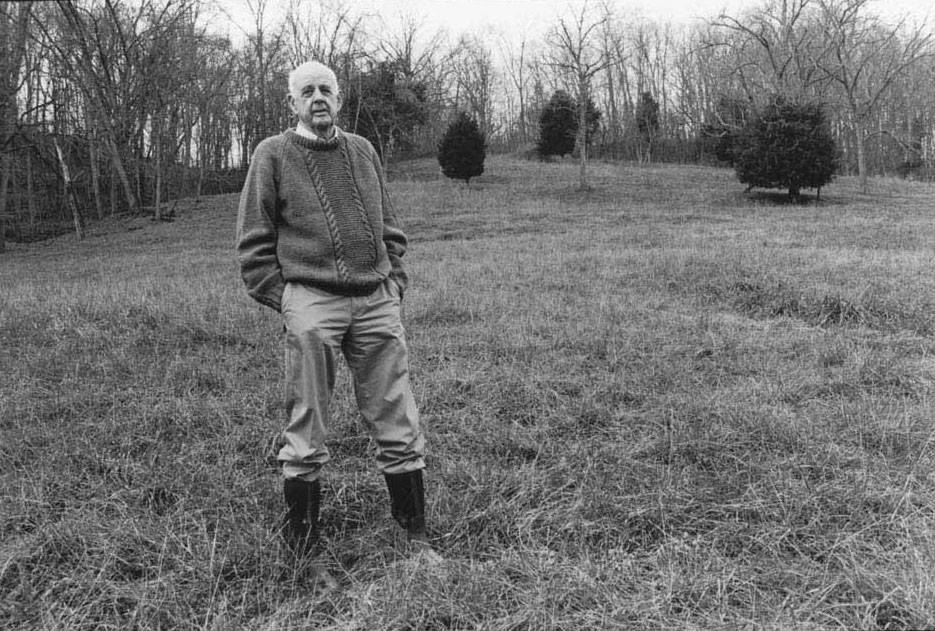

A review of What Are People For? by Wendell Berry (North Point Press, 1990)

“We should love life,” Dostoyevski once said, “more than the idea of life.” It is this concreteness, this rootedness, that seemingly inspirits the life and writings of Wendell Berry, whose most recent collection of essays, What Are People For?, further establishes him as one of the most disquieting yet compassionate and sane commentators on what Berry himself calls “the modem tragedy.” In this book Berry once again extols many of the same virtues-family and community, individual responsibility, meaningful work and measured action. Yet as one reads the essays an important underlying and unifying theme-the struggle to avoid abstraction—emerges, a theme which reveals perhaps Berry’s greatest concern about modem life. By continually reiterating the importance of concrete actions and concrete language, Berry once again warns us of the dangers of allowing corporations, governments, schools, churches or causes to lessen our humanity by defining us and our responsibilities in terms of a subsuming abstraction.

The French philosopher Gabriel Marcel uses the phrase “the spirit of abstraction” to describe “the inability to treat a human being as a human being, and for this human being the substituting of a certain idea, a certain abstract designation.” It is, it seems, against this “spirit of abstraction” that Berry most persistently warns us, for one need only add the words “farm” and “community” to the Marcel quote to get at the heart of not only this latest work but also many of Berry’s other writings.

What can happen to a farm when it becomes “a certain abstract designation” is made clear in this work’s opening and prefatory poem “Damage,” a recounting of Berry’s misguided attempt to build a farm pond on an unsuitable site. When the project fails, Berry realizes that he has himself played out “the modem tragedy.” By relying on generalized expert advice instead of personal knowledge, he makes of his farm an abstraction, and although Berry writes that “[n]o expert knows everything about every place, not even everything about any place,” it would seem that the lesson of the failed pond, as of most failures by experts, is that the particular is the very thing that experts do not know. Later, in the essay “An Argument for Diversity,” Berry states that “[tjhe challenge to the would-be scientists of an ecologically sane agriculture, as David Ehrenfeld has written, is ‘to provide unique and particular answers to questions about a farmer’s unique and particular land.'” For various reasons, primarily financial, it is a challenge that is not being met.

Just as the farmer can do damage by losing sight of the particular, however, so too can the consumer, on whom some of the blame for our current agricultural problems must be placed. Early in the essay “The Pleasures of Eating,” Berry argues for eating as more than an abstract act of consumption:

I begin with the proposition that eating is an agricultural act. Eating ends the annual drama of the food economy that begins with planting and birth. Most eaters, however, are no longer aware that this is true. They think of food as an agricultural product, perhaps, but they do not think of themselves as participants in agriculture. They think of themselves as “consumers.”

Later in the same essay Berry writes that for today’s consumers, “food is pretty much an abstract idea.” This insightful essay, criticizing what Berry calls “the industrial eater,” is an excellent example of how well Berry clarifies for his readers not only the issues but also the implications of the issues. What he senses us losing by “industrial eating” is both complex and important. Corporate food is inferior food in every way except perhaps in convenience, yet even this convenience is gained at a high price. That family meals should be communal and ritualistic has long been one of our region’s strongest unstated beliefs. By eating out at every meal or by buying prepackaged food, we cheat ourselves and our families of the joy and wholesomeness of not only the well-prepared food but also of the ritual of preparation and the communion of the shared table. It is not nostalgia, but common sense, that laments the decline of the family meal.

Extending the problem of abstraction even further, Berry discusses, in several of this collection’s essays, how communities too can be affected by the failure of some organization to see both specifically and wholly. Perhaps the most interesting discussion along these lines is found in the essay “God and Country,” in which Berry criticizes the organized church for having too easy an alliance with “those economic practices that its truth forbids and that its vocation is to correct.” One example of this is the practice of sending out callow ministers into rural areas to receive their training, only to have them return to the city once they have gained experience.

To Berry, this practice is little more than colonialism, with rural areas serving, as usual, as “sources of economic power to be exploited for the advantage of ‘better’ places.” Berry, typically, is careful to note that not all young ministers would be happy and helpful staying in a rural area, but, he goes on to add, in his fifty years in his own community, “many student ministers have been ‘called’ to serve in its churches, but not one has been ‘called’ to stay.”

These questionable church practices, however, only reflect the much larger and much more pervasive pattern of exploitation carried out by the corporations that move into small communities. What these corporations see, of course, is cheap labor, low taxes, and, worst of all, pandering politicians; what they do not see is the fragile web of interdependence that makes a small community so desirable a place to live and so easy a place to destroy. Once the influx of workers begins; once the small, locally owned market is replaced by a Bi Lo; once the McDonald’s moves in; once the weedlike realty signs begin popping up, usually in front of the same houses, it is too late for anything except regret.

It is this loss that Berry sees as inevitable once a community forsakes farming and small business. Typically, this process is accelerated by the indoctrination of the community’s youth, who are encouraged either to move to the city or to return to their hometowns to bring the good news of progress to the locals. One of the great ironies of any faith that a small community may have in higher education is that quite often colleges and universities turn the community’s sons and daughters into professionals so dazzled by the idea of progress that they are blind to the irreparable harm done in its name. As Berry succinctly puts it: “Thus the abstract and extremely tentative value of money is thoughtlessly allowed to replace the particular and fundamental values of the lives of household and community.”

In the twenty essays in this collection, the word “abstraction” (or “abstract”) appears over and over, reiterating Berry’s many concerns with its effects. Another aspect of this concern is evident in the opening essay, “A Remarkable Man,” in which Berry praises the concrete language and actions of a black farmer whose oral history, All God’s Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw, Berry is reviewing. Nate Shaw, the pseudonym of this Alabama-born farmer, had, as Berry writes, an intelligence that “was a meditation upon experience, always related to acts.” It is the particular character of both the man and his language that makes especially unsupportable the claim by some that Shaw is in some ways Faulknerian. Interestingly, Berry attributes this somewhat farfetched notion to misguided liberal sentiments, which, no doubt, is in part the case, but it is useful to keep in mind just how frequently critics fall back on comparisons to Faulkner, Southern literature’s cynosure.

White writers also find themselves gratuitously compared to Faulkner. Perhaps the editor only was trying to encourage serious consideration of a black writer for whom he feared condescension, but, more than likely, he was also demonstrating the same critical Pavlovianism that one sees in so many commentators on Southern literature.

Losing sight of the individual is also an issue in the essay “A Few Words in Favor of Edward Abbey.” Berry’s point about Abbey is that he must be taken as a whole. Environmentalists especially want to claim Abbey for themselves yet are intolerant of the sometimes contradictory and controversial views that he holds. The heart of the matter, of course, is that causes rarely do tolerate diversity of opinion, for all of their talk of open-mindedness and fairness. With Abbey, Berry notes, there is no choice, for “to avail ourselves of the considerable pleasure of Edward Abbey, we will have to like him as he is.” To return to the Marcel quote, Abbey cannot be substituted for an idea, a fact that holds for Wendell Berry as well. Regular readers of Berry know that he much prefers individual action to that of the group, and anyone reading this essay has to feel that Berry is speaking of himself as well when he warns against enlisting Abbey in any cause.

Of the many examples of the subsuming of an individual by an idea, however, none is more telling than that Berry chronicles in the short re-print from Harper’s “Why I Am Not Going to Buy A Computer,” in the subsequent letters to the editors of Harper’s, in Berry’s rebuttal to these letters, and in the essay “Feminism, the Body, and the Machine.” The computer essay discusses why, for various reasons, Berry chooses to write with a pencil and to use his wife as his typist and editor, instead of buying a computer to do word processing. This fairly modest proposal, however, elicits a number of indignant letters to the editor, a reaction Berry attributes in part to his “hav[ing] scratched the skin of a technological fundamentalism.” No specific criticism is more provocative, however, than the charge that Berry is enslaving his wife by having her type and edit his writing. As Berry notes, it is very difficult to defend against attacks on one’s personal life, but he does so, pointedly, especially in the following two paragraphs:

That feminists or any other advocates of human liberty and dignity should resort to insult and injustice is regrettable. It is equally regrettable that all of the feminist attacks on my essay implicitly deny the validity of two decent and probably necessary possibilities: marriage as a state of mutual help, and the household as an economy.

Marriage, in what is evidently its most popular version, is now on the one hand an intimate “relationship” involving (ideally) two successful careerists in the same bed, and on the other hand a sort of private political system in which rights and interests must be constantly asserted and defended. Marriage, then, has now taken the form of divorce: a prolonged and impassioned negotiation as to how things shall be divided. During their understandably temporary association, the “married” couple will typically consume a large quantity of merchandise and a large portion of each other.

The irony here, of course, is that enslavement of any sort, whether by another person, by a machine, or by an idea, is fundamentally contradicted by all that Berry espouses. Indeed, enslavement of another sort is what characterizes these feminist ideologues who fail to see the unfairness (and irony) of expecting others to sacrifice personal choice to political correctness.

Berry’s original essay and his response to the Harpers’s letters should be required reading in all freshman English classes (and beyond, of course); however, it is likely that only the original essay will be taught, probably as an example of how blind a writer can be to the implications of his own words. Perhaps such pessimism is unwarranted, for Berry’s other writings are beginning to make their way into that great marketplace of ideas-the freshman reader, and, with our country’s growing ecology movement, general interest should continue to increase, also. That Berry is being read by more people is of great importance to us all, for we will ignore him at our own peril. Because our lives are so circumscribed by “the spirit of abstraction,” it is especially important that this latest collection be read and contemplated, not only because we share Berry’s love of “light, air, water, earth; plants and animals; human families and communities; the traditions of decent life, good work, and responsible thought; the religious traditions; the essential stories and songs,” but also because we must constantly be reminded of what Paul Johnson calls “the utter heartlessness of ideas.”

This review was originally published in the Third Quarter 1990 issue of Southern Partisan magazine.