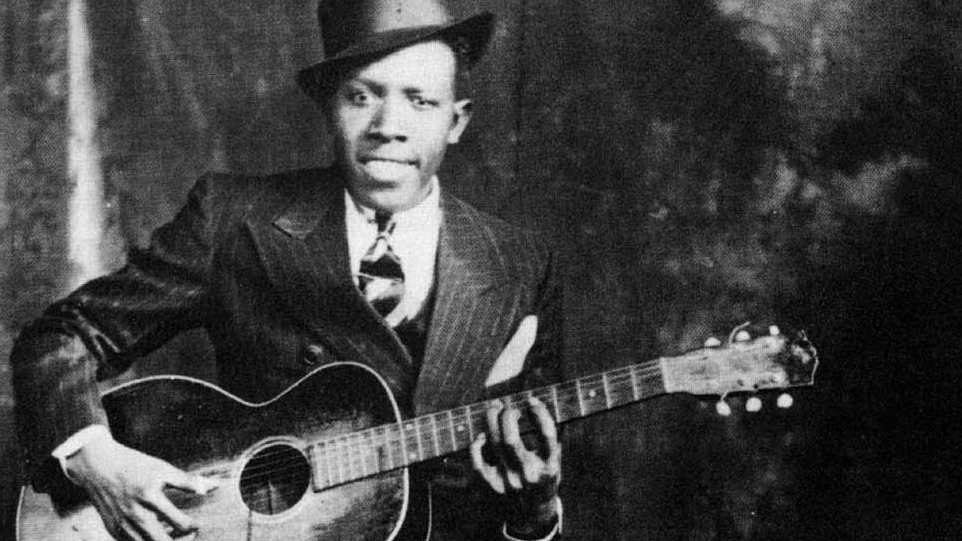

The sixth Southern musician to be examined in this series of What Makes This Musician Great will be a bluesman that was so good he became a ghost story – Robert Johnson.

The Blues is probably the most significant musical form created anywhere in the world in the 20th century, and it absolutely came straight out of the Mississippi Delta, which is the floodplain area of the Mississippi River that extends into Mississippi, Arkansas, and Louisiana. “The Blues” is actually two different things – “Blues” refers to a major genre of American music, and “12-bar Blues” refers to the structural form of “The Blues,” which can be applied to music composed in practically every other genre and style available. Obviously, Blues songs are in 12-bar Blues form, but so are many Rock songs, Jazz songs, Country songs, Tejano songs, Cajun songs, etc. Someone could even compose an opera aria in a 12-bar Blues form if they wished.

The Blues evolved from Black field songs and work songs in Dixie around the turn of the 20th century. It was not formally composed or written down, but learned and passed along by the memories of travelling musicians, which makes it impossible to pinpoint an exact beginning. However, we know that Ragtime piano songs began featuring small sections within the composition that were in a 12-bar form, and around 1910, several composers began publishing them. It’s difficult to know which one was first, but Alabama composer W.C. Handy billed himself “The Father of the Blues” when he published a piece called “Memphis Blues” in 1912. Since Ragtime was a genre of piano, then technically Blues began as a piano style. However, when the travelling storytellers of the Mississippi Delta began adapting the Blues form in the 1920’s and playing it on guitar (a much more portable instrument than piano), that’s when things really took off. It was during the 1920’s and 1930’s that those pioneering travelling Blues men were first recorded, and among them was Robert Johnson.

And that’s where the ghost story comes in.

When he was just a kid in Mississippi, Robert Johnson learned to play the Blues on harmonica, and was known among local musicians as a competent player – not great, but not bad. Then, he went away for a while to handle some family business, and when he returned, he was suddenly a master of the Blues guitar. He could play like no one they’d ever heard before. This time, the local musicians not only took notice, they were suspicious. They reasoned that only someone who had made a deal with the Devil could learn how to play that good that fast. And the legend stuck.

Trading one’s immortal soul to the Devil in return for an earthly treasure is a 15th century German legend, and it plays perfectly into Robert Johnson’s myth. As the story goes, Johnson met with the Devil down at “the cross roads.” He handed his guitar to the Devil, who played it, and then handed it back. From that point forward, Robert Johnson could play the Blues like a man possessed – perhaps literally. He recorded three specific original songs that also folded right into the legend – “Cross Road Blues,” “Me and the Devil Blues,” and “Hellhound on My Trail.” The fact that he died young right on the verge of a live appearance at Carnegie Hall only added fuel to the fires of his supposed damnation.

I actually have my own theory as to how Robert Johnson was able to go away and come back with insane talent on guitar. I believe … he practiced. But that’s just me.

By the way, Robert Johnson was also the beginning of something else creepy called “The 27 Curse.” He was 27 years old when he died unexpectedly, and there has been an unusual number of young famous musicians who also died at the same age, such as Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Kurt Cobain, and Amy Winehouse.

Robert Johnson was raised as a sharecropper in the Delta, and he hated it. Rather than continue along that difficult, backbreaking path, he chose to be a travelling Blues man instead. He ranged all over the Delta, going from town to town by hitching rides (cars, trucks, or even tractors), hopping on trains, or simply walking. Upon arrival in a new town, he would head for the barbershop if it was daytime or juke joint if it was night, stand on the sidewalk, and play the Blues. Usually a crowd would gather, and he played and sang for his supper, boarding, and companionship. Therefore, his “fame” spread only in the Black communities around the Delta, until a druggist in Jackson, Mississippi heard him play and arranged for him to travel to San Antonio and make some recordings. After hearing the records, jazz promoter John Hammond included him in a concert he’d organized at Carnegie Hall in 1938 to feature Black music, but Robert Johnson died four months before the performance took place. If it were not for those 29 songs he recorded in two different sessions in Texas, his unbelievable legacy would have never been realized beyond his lifetime.

The 12-bar Blues style is one of the easiest things for a non-musician to hear in music. It requires no training and no talent in order to hear it. If you can count to 12, and if you can tell whether two things match or are different, then you’re all set to listen to the Blues. Here’s how it works.

Any song in 12-bar Blues form has each verse comprised of 12 measures that are divided up into three phrases each – 4 measures per phrase. The first two phrases match each other, and the third phrase is different, giving it an AAB form. Using the lyrics of Robert Johnson’s song “Cross Road Blues,” here’s an example.

PHRASE 1 (A) – I went to the crossroad, fell down on my knees.

PHRASE 2 (A) – I went to the crossroad, fell down on my knees.

PHRASE 3 (B) – Asked the Lord above, “Have mercy, save poor Bob if you please.”

Do you see it? The first two phrases match, and the third phrase is different – AAB. This 3-phrase pattern is repeated throughout the entire song, and if you did nothing but spend the entire song counting the measures and phrases, you’d still have a productive and rewarding listening experience. There are some more sophisticated harmonic structures to consider within the form (if you understand a little music theory), but you can enjoy the Blues for the rest of your life perfectly fine without that. As I mentioned, every single verse in “Cross Road Blues” is in this same form, and it’s very easy to follow. Plus, it works with all the other songs of Robert Johnson, as well as all the songs of Son House, Muddy Waters, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Dixon, T-Bone Walker, John Lee Hooker, B.B. King, Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and ALL of them. Perhaps the most magnificent thing about 12-bar Blues is its utter simplicity, and that’s why it is so incredibly versatile. It’s just as easy to spot the 12-bar Blues form in songs by Robert Johnson as it is in songs by Hank Williams, Carl Perkins, Ray Charles, Louis Armstrong, The Allman Brothers Band, or even The Beatles.

So how does this differ from other musical forms? The difference is in the “12-bar” part. Most songs in Western music – sacred or secular, silly or artfully composed – naturally fall into a 16-bar pattern in four phrases. Our ears tend to favor songs that are balanced and symmetrical this way, and the four phrases are either AABA, AABB, or ABAB. Probably more than 90% of all Western music is composed this way, but not 12-bar Blues. The Blues are jarring to the senses because they are missing a phrase (three phrases instead of four) and are missing some measures (12 measures instead of 16). When you are subconsciously expecting a song to flow into that fourth, balanced phrase, it’s a bit of a jolt when it’s suddenly not there, as if you had the rug pulled out from under your ears. For this reason, any song in 12-bar Blues was composed that way intentionally. Songs don’t just spill out of a composer’s head and randomly fall into an accidental 12-bar Blues form. The composer has always chosen to follow the 12-bar Blues form purposefully and sticks to it throughout the creative process.

But remember – Robert Johnson isn’t known for innovating the 12-bar Blues form, since it was already there when he came around. He’s known for innovating the Blues guitar and voice, so let’s get into that.

Robert Johnson played a “steady bass” guitar style, which means that the right-hand thumb only picks a singular root bass note, and not a “bass line.” The rest of the right-hand fingers each pluck an individual string at the same time, which gives the whole right hand a claw-style motion. Imagine holding up your hands as “monster claws” as if to scare someone. Now, imagine plucking guitar strings with your hand in this exact same position. The whole right hand is held with all the fingers in a specific position as the strings are plucked, and it is very similar to the claw hand position used to pick cotton. My grandmother once showed me how this hand position is vital for picking cotton, because once the petals of the cotton boll open up and peel back, they harden into very sharp points. The claw hand position allows your fingers to grab onto the soft cotton between the sharp points and pluck it without getting stabbed. Cotton pickers learn the necessity of keeping their hands in this claw position in order to pick cotton quickly without getting cut to pieces. In my opinion, this would be a perfectly natural guitar plucking hand position for a former Mississippi sharecropper.

Sometimes, Robert Johnson tuned the guitar in non-standard ways, which allowed his left hand to slide around in unique positions on the guitar neck, playing chords and individual melodic notes simultaneously. This trick often made it sound like two guitars being played at the same time, and that was the main part of his iconic sound that created his supernatural legend. In his lifetime, many were convinced that a “ghost guitar” was somehow playing along with him, and even today, accomplished guitarists remain amazed that only one guitar could sound like that.

And then, there’s his voice. First, think of a piano keyboard with white and black keys, and then picture a white key with a black key on either side. Three notes – black, white, black. What if you wanted to hear a note that was somehow in between the black key and white key? How could you play that? Well, you can’t on a piano – but you can definitely sing it with your voice. You can easily sing pitches that are in-between standard pitches, and this is what gives the human voice its trademark “crying” sound. Robert Johnson made a career out of living in the land between pitches, and oddly enough, these “in-between” pitches are musically known as “blue notes.” Doesn’t it make perfect sense that “The Blues” are loaded up with notes called “blue notes?” However, there is a VERY fine line between singing blue notes and simply singing out of tune. There is a lot of highly sophisticated vocal control needed in order to make your voice sound “blue” instead of off-pitch, and this is another area where Robert Johnson excelled. He always made his voice walk the line between singing and crying, and it is spine-chilling to say the least.

And to top it all off, Robert Johnson could bend his guitar strings or use a bottle-slide in order to reproduce these same in-between vocal blue notes on his guitar. His voice cried, and his guitar cried right along with it. It was the sound that created both a legend and a ghost story, and the best part is that you don’t need musical training to hear it. His eerie sound is not buried like an Easter egg deep in the song – it’s right out in the open for anyone’s ears. When you listen to Robert Johnson, listen for the frequent appearance of a second “ghost guitar.” Listen for a crying voice that mimics a crying guitar, and vice versa. However, be mindful that the crying is only used as an effect – it’s not the dominant sound of the whole song. His recordings don’t sound like a man openly sobbing and weeping throughout the lyrics. Rather, it’s an occasional phrase here, or an unexpected word there which gives it the “soul” that we recognize.

“Cross Road Blues”

If you research this song yourself, you will be submerged into all the internet material dealing with the Faustian legend of Johnson selling his soul to the Devil at the Crossroads, but you won’t find much information on why it’s simply a great song. So, forget the creepy ghost story for now. Let’s look at the music first, and then come back later to add the significance of the lyrics.

As described earlier, the song is in 12-bar Blues form, and the first verse could be analyzed as the following:

PHRASE 1 (A) – I went to the crossroad, fell down on my knees.

PHRASE 2 (A) – I went to the crossroad, fell down on my knees.

PHRASE 3 (B) – Asked the Lord above, “Have mercy, save poor Bob if you please.”

Each subsequent verse follows this exact same 12-bar Blues format, as it should, but you can hear every technique described above all in the very first verse. Steady bass, claw hand plucking, slide guitar that sounds like a weeping voice, a weeping voice that sounds like a slide guitar, blue notes, and the uncanny sound of a second guitar coming from somewhere. Many times, Robert Johnson will end a vocal phrase on a particular note, and then punctuate that single note by plucking it on the guitar. There is a 7-second guitar intro, which musicians use many different terms to describe, such as a “tag” or a “turnaround,” and it is like a small slice of Blues that can be used as an introduction, an ending phrase in verses that connects to the next verse, or the ending of the song entirely. There are five verses in the recording each one about 35 seconds, and it ends with that same 7-second guitar tag.

Although the lyrics adapt easily to the Devil legend, I’ve always interpreted them to refer to any indecisive crisis that someone may face in their lives. Robert Johnson is at a figurative crossroads, and a great weight is placed on him to make the right decision. Although he looks around for others and even asks God for help, there will obviously be none coming, and whatever it is will all be on his shoulders alone – and he feels like he’s blowing it.

“Kind Hearted Woman Blues”

This song is a good example of the flexibility of the 12-bar Blues form in its early, formative days. If you tried to score this music and count out the number of beats and number of measures, it won’t add up. Some of the phrases are missing beats and measures, while others have too many beats and measures. It would be a train wreck to try this with a band, and the only way a performer can pull this off is to be playing and singing alone, as was the case with Robert Johnson. However, this is definitely not an indication that the Johnson was ignorant of the form, but is highly indicative of a someone performing interpretively. In the 19th century, classical music was performed this exact same way – a composer like Chopin would write the notes on a page, but leave it up to each individual performer as to their own personal interpretation of the steady beat and style. Therefore, each musician who plays Chopin plays him differently, which is exactly what Chopin wanted. Robert Johnson works the same way – three different performances of “Kind Hearted Woman Blues” would have sounded three different ways, depending on Johnson’s mood.

Specifically, listen for the weepy sound to his voice in the second verse, and the way the guitar imitates it. Also, listen for the Blues guitar “tag” that connects each verse. There is an instrumental guitar solo between the third and fourth verse as well.

“Hellhound on My Trail”

Straight up, this song is a musical nightmare, and is the kind of song that’s uncomfortable to listen to late at night, alone, and with the lights out. Robert Johnson takes his cues from his own disturbing lyrics for making both his voice and his guitar howl. There are howls of pain as well as howls of pursuit, and this song is a chiller. The bass notes keep repeating over and over (indicative of a relentless pursuit) while the bottleneck slide recreates the high-pitched howling sound.

The 12-bar Blues form is extremely stretched out in this song, and this is another one where you might get lost if you tried to strictly count the number of beats and measures. The lyrics are very indicative of the threat of hell hounds chasing down sinners to make them pay for their transgressions, and the gospel/spiritual influence on the song is obvious. It has four verses, and Robert Johnson even sings a gospel-style call-and-response with himself several times within the verses.

Robert Johnson did not invent the Blues, and he came along too late to even be considered for the early development of the Blues. By the time he was first recorded in 1936, all of the format known as 12-bar Blues was already firmly established. However, what Robert Johnson brought to the table was an eerie mastery of the guitar that transformed standard Blues into something haunting and intense, which would directly inspire generations of guitarists in the 1950’s, 1960’s, and beyond. Simply put, Robert Johnson was more than a Blues pioneer – he was a Blues GUITAR pioneer.