A review of How Radical Republican Antislavery Rhetoric and Violence Precipitated Secession, October 1859 – April 1861 (Abbeville Institute Press, 2022) by David Jonathan White.

One of the tragic casualties of America’s long culture war is the distortion of the country’s central event, The War Between the States. During the 1950s, historians such as Avery Craven began to question the “irrepressible conflict” thesis favored by most historians. As Bruce Catton wrote in a review of Craven’s book, The Coming of the Civil War, Craven and “a highly industrious school of historians has been asking whether the war should have been fought at all and whether it was perhaps not more the fault of the North than of the South.” Criticized at first for being revisionist, later assailed by the neo-abolitionist culture warriors of the 1960s as pro-Southern, Craven and other historians seeking a detached and objective account of the war fell out of favor. In the last sixty years or so the historian as activist for the cause du jour now rules supreme in the departments of history in the United States. Causes and fashions may change, but one thing remains the same, an uncompromising assertion that slavery was the cause of the war and the accompanying demonization of the South.

Even in the hands of seemingly deft and balanced historians, the narrative of causation dominant in the field is simple and inflexible. Northern moral sensibilities became outraged over the existence of slavery in the United States as Southern anti-slavery voices went silent. As territorial expansion proceeded, the Northern moral impulse became steadfast in refusing to allow slavery to spread into the western territories, whereas Southerners insisted upon the spread of their peculiar institution into the same. With the election of a sectional president, Abraham Lincoln, committed to halting the westward expansion of slavery, even as he promised to not interfere with slavery where it existed, Southerners thought themselves and their institution threatened and decided to leave the Union. Thus, the war came. The more activist oriented and politically motivated historians add to the above interpretation condemnations of Southern racism, white supremacy, and a full embrace of the most wonderful and paranoid of American conspiracy theories, the evil machinations of the “Slave Power.”

The careful reader and student of logic may have already identified several questions left unanswered by the dominant interpretation. First, if the South secedes, doesn’t this effectively defuse the conflict regarding the spread of slavery to the territories? Second, why does the South feel threatened by Lincoln’s election? True, the western territories would be closed, but the proposed Corwin Amendment supported by Mr. Lincoln would provide slavery with explicit and ironclad constitutional protection. Third, why exactly is the North adamant about opposing Southern secession? These unanswered questions invite a very thorough and patient study in several fields: history, semiotics, economics, and politics to achieve a satisfactory understanding as to why the war came, or more accurately, why secession and war—two very different and distinct things—were chosen by the historical actors of the 1850s and 1860s.

Jonathan White does us the good service of attempting an answer to the second question, why is the South threatened by Mr. Lincoln’s election? White frames the question in more narrow terms. What moved Southern moderates and Unionists who opposed secession in 1858 to embrace secession in 1860-61? White’s answer to this question is more nuanced and complex than repeating the magic mantra “slavery.” Some historical context is helpful in fully understanding White’s argument. The Dred Scott decision in 1857 repealed the Missouri Compromise and opened the western territories to slaveholders and their property. Nevertheless, very few Southerners were taking their slaves into Kansas or any other territory. Apparently the “Slave Power” faltered badly at the very moment of its great triumph. Stephen Douglas, a senator from Illinois, was much more the hard-headed realist than the Slave Power conspiracy theorists. Douglas knew Southerners were reluctant to settle with their slaves in Kansas. Thus, his advocacy of the doctrine of “popular sovereignty,” a political sleight of hand that obscured a fait accompli. In Douglas’s correct view, antislavery settlers would quickly outnumber slaveholders in the territories and pass territorial and state constitutions outlawing slavery. Northerners need only be patient and the powers of the federal government would fall into their lap. Of course, Southerners could count too. They knew full well that the result of “popular sovereignty” would be a Congress and Presidency dominated by sectional interests resulting in a program of financial and political consolidation financed in large part by high tariffs. These issues were intertwined, much like a pile of fishhooks, where an attempt to remove one hook results in lifting the entire tangle of issues. Separating this tangle was no easy task.

Slavery was of course the political issue that generated the most excitement and division. The Dred Scott decision, the Fugitive Slave Act, and on the eve of war the proposed Corwin Amendment and its guarantee of federal protection of slavery in the states where it existed did not allay Southern fears regarding the abolition of slavery and its consequences. The Abolitionists and their intellectual progeny, who claimed the existence of a “Slave Power” bent on extending slavery throughout the Union, were immune to the lack of evidence of a vast Southern slaveholder migration extending throughout the country. The “Slave Power” conspiracy was useful to its adherents in explaining away judicial and legislative defeats, economic distress in the rural areas of the Old Northwest, the Panic of 1857, and the violence in Bleeding Kansas. The Republican triumph in the election of 1860 allayed Northern anxieties, but it elevated Southern fears. The Corwin Amendment was an olive branch designed to entice the already seceded states back into the Union, and to keep the wavering border states and upper South in the Union. Why did Southern politicians not jump at the Corwin Amendment, an amendment supported by the newly elected President Abraham Lincoln? What accounted for Southerner’s deep distrust of Republicans and Northerners?

Jonathan White’s important book addresses these questions. White begins where all good historians begin, by understanding historical actors as they understood themselves. Southern conservatives and Unionists are the focus of White’s attention, they are the key swing vote whose views must change if secession is to become a reality in the South. Throughout much of the trying decade of the 1850s, these men of moderate and conservative principles remained steadfast in their attachment to the Union. By 1858, fear began to erode the attachment these men had to the Union and fear drove them to ultimately throw in with the secessionists. This fear was driven by the violent rhetoric and the violent actions of antislavery Northerners and the inability of many conservative Northerners to oppose and universally condemn the same.

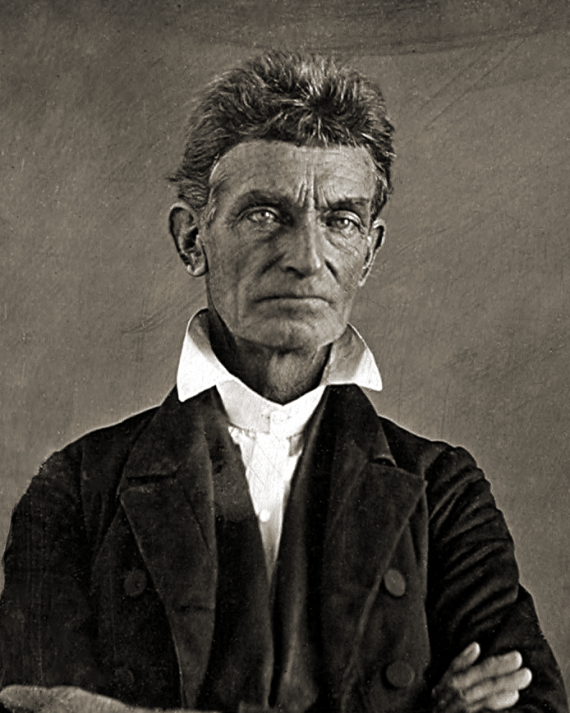

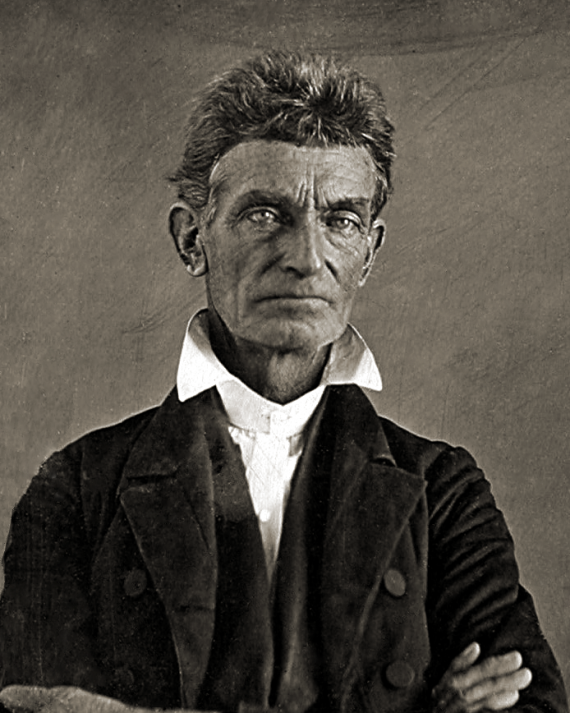

The divisive and polarizing rhetoric of Northern antislavery politicians first emerged in force during the debates over the admission of Missouri as a “slave state.” By the late 1850s, however, the rhetoric of many antislavery politicians and intelligentsia grew violent in its imagery and its proposals, and it was not limited to just a few select partisan politicians and newspaper editors. Throughout the North, politicians and the intelligentsia lent their active material support to those, like John Brown, seeking to incite a violent slave insurrection. John Brown’s raid stoked the fires of division, but the rhetoric of Lysander Spoon, Brown’s canonization by Ralph Waldo Emerson, the financial and material support given to Brown by the not so “Secret Six,” and the failure of Northerners as a body to condemn antislavery violence. In some cases, some of Brown’s people were shielded from extradition to Virginia. These factors drove many Southern conservatives and Unionists into the secessionist camp. Without this shift, secession was at best a doubtful prospect. As White demonstrates, the Brown raid became the lens through which the South viewed any suspicious actions, persons, or crimes. Quickly thereafter, the South took steps to secure its internal security.

As the election of 1860 neared, Southern fears for their internal security were not allayed. Democratic candidate for president, Stephen Douglas, firmly opposed secession as a remedy for Southern security fears. To his credit, Abraham Lincoln condemned the actions of John Brown, but Southerners wanted much more from the man who authored the “House Divided” speech. As for the other leading Republican candidate, William Seward, the best he could muster on the antislavery violence issue was silence. It is no small wonder that the electoral victory of the Republicans, which for the first time placed the reigns of the federal government in the hands of a sectional party, was read by many Southerners, radical and moderate, as a sign of the North’s bad intentions. The lower South seceded. The upper South hesitated, until Lincoln’s unconstitutional call for militia and his military occupation of Maryland left no doubts in their minds. The trend was confirmed, the North had chosen the path of political violence to resolve the crisis.

White’s book is important not because it provides us with a fuller understanding of why Southerners chose secession. His evidence is broad, encompassing the written and spoken word, as well as empirical data on the vote shifts in the secession conventions from union to separation, and the internal security preparations undertaken by Southern counties and states. White also offers a balanced account, he affirms that Southerners at times overreacted to rumors of abolitionist interference with slavery in local areas or to crimes of uncertain origin, but their response was understandable given the rise of the culture of political violence. The result is a provocative work. White examines how the threat of Northern political violence, what some may refer to as terrorism, impelled many Southerners of conservative and Unionist sentiment to view secession as the most prudent and reasonable course of action given the circumstances. Indirectly, White’s book introduces the important role violence and the threat of violence played in both the antislavery movement’s actions and rhetoric and in the political culture of the North. Certainly, the advocacy of and material support given to violence on the part of large numbers of prominent and influential Northerners was an essential cause for many Southerners to embrace secession. Jonathan White not only broadens and deepens our understanding of the causes of secession, but he reveals the important role public violence played in the political culture of the North, a topic that needs further and deeper study.

It is a paradox, but the time is both inopportune and opportune for such a study as Mr. White’s. It is inopportune in that the academy is in no mood for a consideration of the dark side of the antislavery cause. The 1850s was prelude to the brutal and savage actions of the Federal war machine in Georgia, South Carolina, and Virginia—all in the service of a “righteous cause.” Moral crusades attended by public violence is an old game with a deep tradition up North, especially in New England. Examination of conscience is not a strong suit of the Yankee intelligentsia. In these days of woke rage in which we find ourselves, Mr. White’s book will be dismissed as Confederate apologia at best. Yet for those with eyes to see, Mr. White sets a rhyme of history before us. Call it what you will: critical race theory, cancel culture, the reign of “wokedom,” or cultural Marxism, the self-righteous indignation is the same, the hypocrisy has not changed, the calls for violence echo the past. Mr. White’s Southern Unionists did not see the danger until it was upon them, but they acted in a way that they viewed as necessary to their security and preservation. In the past the lines of conflict, fell along well defined geographic and political boundaries. The boundaries are less well defined today, at best they resemble the old court and country conflicts of the colonial period. Yet one cannot come away from Mr. White’s book without a sense of here we are again.

Regardless of the times, Mr. White has taken a large step in moving the discourse on the war and secession away from the simplistic cant and mantra of “slavery.” He has deepened our understanding of why Southerners embraced secession and opened new paths for historical inquiry. One can ask for little more from a scholar toiling in the field of history. Future generations of scholars who come after our post-rational era will be grateful to him.

I read a book once by a famous Yankee author…it was actually two books…he blamed the South for the War…and he NEVER mentioned the Corwin Amendment.

Many thanks for this review of the next book on my reading list.

Dr. Devanny, your article trikes a chird with me. I just finished writing a historical novel, “The Last of Sapelo: The Randolph Spalding Story” Your article has reassured me that my postion with the Spalding family of McIntosh County, Georgia reflects how a Southern Conservative, a staunch Unionist, family got pulled into supporting Georgia once Secession appeared unstoppable by early 1861. Thomas Spalding the patriarch of the family kept Georgia from Secession in 1850, but his surviving sons could not overcome the election of Joseph Brown and his Secessionist allies in Milledgeville. Randolph Spalding, Thomas Spalding’s youngest son and arguably the most successful planter after his famous father’s passing in 1851. My research depicts Randolph and his older brother, Charles Spalding as reluctant Georgia patriots. They and the other Spalding family members by marriage rallied to the cause to defend their lands, lifestyle, and legacy. In fact, the Spaldings during the war often faced the challenge and great expense of relocating their slaves inland while also serving in the CSA/Georgia Militia as the Union threatened the coast. The Rhett family of Beaufort and the Spaldings often were at odds before the war, yet when Port Royal came under attack Colonel Randolph Spalding found himself in the fray on Hilton Head Island, and then served as an aide-in-camp to General W. H. T. Walker in Savannah and sat in with meetings at Headquarters in Savannah where Robert E. Lee failed to quell the Union threat once they gained a foothold on Georgia soil at Tybee Island. What was the aim of the Lincoln’s Naval Armada? Seize the cotton in the key ports to feed the Northern textile mills while choking the South off from vital trade with England. In my story I speak of the hypocricy of the North wanting all the cotton it could get and at cheap prices thus furthering the use of slaves to cultivate and harvest the “white gold” to line their pockets on the backs and toil of their own millworkers, men, women and children enslaved economically in northern mill towns.

It os a sad tale. Colonel Randolph Spalding died of pneumonia in Savannah in March 1862, but his legacy lived on. In 1868, his brother Charles helped Randolph’s widow, Mary, and their three children resettle Sapelo Island. She sold off some of the land on the island to finance the rebuilding of their homes and their new lives with the help of the freed slaves who virtually ALL returned to Sapelo after the war. Until Howars Coffin bought Sapelo inthe early 1900s, the Spalding family lived on Sapelo as the only white residents among upwards of 400 former slaves. That fact alone drove me to write the story (a historical novel, deeply rooted with historical facts, people, places and events).

My proposed novel now faces the daunting task of finding an agent and publisher willing to invest in it knowing the socio-political climate we live in today. But it can become a story to stir real conversation on the misconceptions and untruths that have torn our coutnry apart once agian.

Thank you and the others at Abbeville Institute.