Peter Thiel, a co-founder of PayPal along with Tesla’s Elon Musk and an early Facebook investor, is famed for his thought-provoking questions. One example is a question he typically asks entrepreneurs seeking venture capital from him: “What are you certain to be true that most of your peers would disagree with you about?” Copernicus, for example, might have answered that the solar system is heliocentric instead of geocentric as was commonly supposed in his day.

A similar question concerns the wisdom of crowds. Think back to 2004 when perhaps two-thirds of homeowners believed real estate prices would continue to rise. The ensuing rise reflected “the wisdom of crowds.” But in 2008 when over 90% of homeowners acted as if prices would continue to rise indefinitely the result was a speculative bubble that reflected “the madness of crowds.” Thiel’s point is that our challenge is to try and identify when “the wisdom of crowds” transitions into “the madness of crowds.”

This can be applied to Civil War history. When two-thirds of historians contend that slavery was a prime reason for the secession of the seven cotton states, they were probably right. But when 98% believe that it was the only important cause of secession and that secession caused the war, they are probably wrong. Instead of thinking things through for themselves, they yield to a herd instinct. And the only way to validate the herd is to extrapolate the stampede of condemnation for the South until the tenets collapse upon themselves. Such extrapolation has already become manifest in several ways.

One is demands that Confederate statues be contextualized, escalating into removal, and escalating again into outright destruction via meltdown. Another way is failing to recognize that the Confederate Constitution banned subsidies for private industry, restrictive tariffs, and public works spending, three non-slavery reasons for forming a new nation. A third way is to completely miss the point that the seven cotton states could have been allowed to leave peacefully thereby enabling both sides to avoid the Civil War and ridding the Union of slavery. A fourth is to realize that it was the North that went to war over tariffs, not the South. The North wanted restrictive tariffs to transform their leading manufacturing sectors into virtual domestic monopolies.

Peter Thiel uses a couple of rules of thumb to identify when “the wisdom of crowds” has transitioned into “the madness of crowds.” First, is to be aware when “Opinion X” dominates over “Opinion Not-X.” When the first opinion dominates there is little examination of its weaknesses. Second, and foremost, is when advocates of “Opinion X” have become so powerful that they do not permit debate and censor dissenting voices. When that happens Thiel concludes that “Opinion Not-X” is more likely the valid one.

In terms of Civil War history, the dismissal of dissenting voices as so-called Lost Cause Mythology suggests that the conventional wisdom regarding the causes of the war and the comparative morality of the respective sides has “transitioned into the madness of crowds.” It explains the mania to demonize the Confederacy and even the Confederate soldier without debate. It explains why PhD students will not undertake any research projects that fail to support the North-Good, South-Bad dichotomy. It explains the monopolization of a one dimensional opinion within the academy, journalism, and the cultural elite generally.

Let them take note: Nine days before the October 1929 stock market crash that led to the Great Depression of the 1930s, Yale Economics Professor Irving Fisher stated that stock prices had “reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.” He was among the madness of the crowd. It is significant to note that Fisher was an academic expert, much like many Civil War historians today. Unfortunately, academics are among the most vulnerable to a herd instinct because they are risk averse. They cannot stand the embarrassment of condemnation by their colleagues.

@ Half the crowd has an IQ below 100. Their votes count the same as Solomon’s.

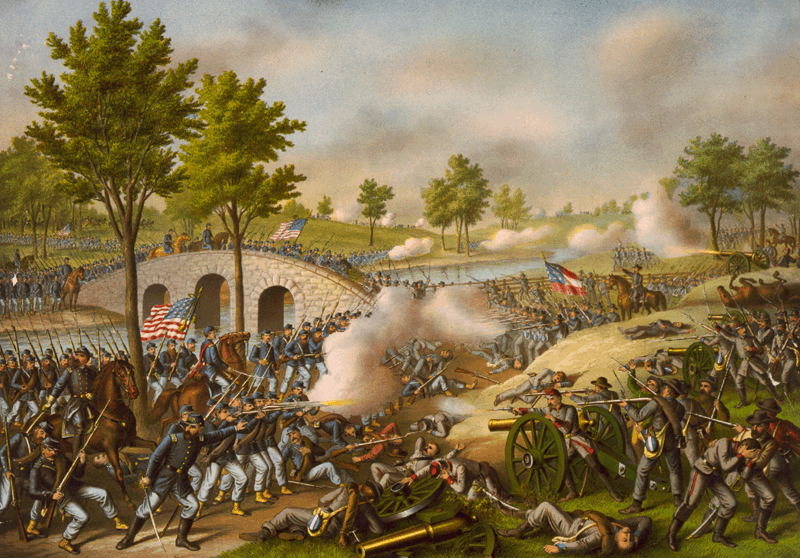

Americans are justly famed for their study of the 61-65 war. For foreigners we are equally fascinated by the ebb and flow of the tide of war. The war often reflects the divisiveness of similar wars in our own countries. Our interest is also in the sharp divisions which Americans are prepared to study and discuss. All this is admirable.

But we come to the crux. That being the far fewer honest and fair studies of why war broke out, and as Abbeville Institute points out the experience of reconstruction. If Abbeville Institute concentrates (not exclusively of course) on these periods your work will contribute soundly on issues that touch our human experience.

Congratulations on changing at least one person’s (mine) appreciation of especially ‘reconstruction’.

Another source for a parallel subject is Shotwell Publishing’s “The Union League” which used free blacks to tyrranize the post war South.