After Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers on April 15, 1861, to force the seven cotton states back into the Union, four Upper South states—Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas—seceded and joined the Confederacy. They deemed Federal coercion against any state to be an unconstitutional abuse of power. Maryland’s experience underscores the point.

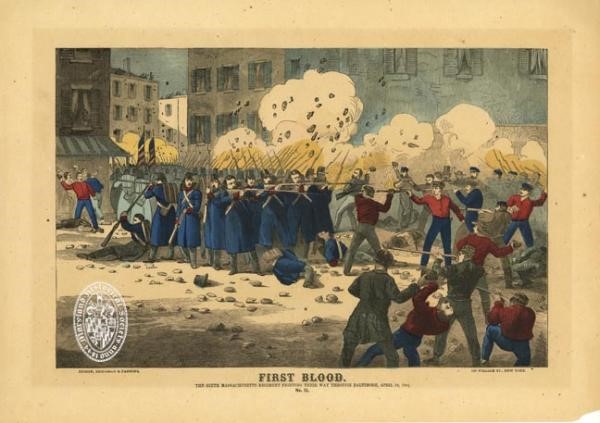

The first fatality of the Civil War was a Baltimore man, shot by Massachusetts soldiers during a confrontation as the soldiers marched through the city on April 19, 1861. Lincoln claimed they were on their way to Washington to rescue the Federal Government from potential Confederate invasion. Baltimoreans, however, regarded the soldiers as intruders come to interfere in the internal affairs of a sister state. Both were correct, but Lincoln’s version dominates the history books.

Attempting to prevent further incidents, on 20 April Maryland officials burned the railroad bridges on Baltimore’s North side, blocking easy access to the state from the North. On 22 April Governor Hicks announced that the legislature would convene on 26 April to address the secession crisis. Since Federal reinforcements occupied the state capital at Annapolis, he directed the General Assembly to gather at Frederick, about fifty miles northwest of the White House.

On 25 April Lincoln gave General of the Army Winfield Scott powers to secure a path through Baltimore. First was authority to suspend the writ of habeas corpus. He could impulsively arrest anyone he wanted. Second, he was to “watch” the General Assembly and oppose with military force any effort they might make to arm Maryland residents “against the people of the United States” . . . “even” . . . “to the bombardment of their cities.”

The Assembly did not attempt to secede over the summer. Members realized that Lincoln’s growing garrison would crush any attempt, violently if necessary. Instead, they passed resolutions critical of Lincoln. One asked him to cease his “unholy” war against the Confederacy and recognize it as an independent nation. Another declared his “military occupation of Maryland a flagrant violation of the Constitution.

As Lincoln’s army grew, Hicks increasingly sided with him during a series of short assembly sessions. During June and July, he focused on getting the Maryland Militia to return their borrowed firearms to the state. The object was to remove the guns from Southern sympathizers and gain control of the Militia. Finally, on August 7, 1861, the Assembly ended a session and scheduled to reconvene it on September 17, 1861.

The General Assembly had a total of 74 members, 14 in the Senate and 60 in the House of Delegates. By suspending the writ of habeas corpus, Lincoln had 31 of them suspected of being Southern sympathizers imprisoned. Others were thereby intimidated into avoiding the 17 September session out of concern that they would be arrested if they showed up. While the number of intimidated is unknown, the official reason for not holding the 17 September session is that it did not have a quorum. If the 31 arrested were members of the House, their arrests alone would have blocked a quorum.

While it is impossible to know whether Lincoln’s usurpation prevented Maryland’s secession, at least one authoritative participant concluded that it did. Specifically, Assistant Secretary of State Fred Seward, who was the son of Secretary of State William H. Seward and involved in the arrests, wrote in his reminisces after the war that he believed the session of the Maryland General Assembly scheduled for September 17 would have voted to secede, although they may have been required to first set-up a secession convention.

Lincolon was our first communist president. He will be scorned throughout history as destroying the original republic and creating a fedgov capable of taking away your rights.

Its first act was to declare an illegal war to keep the South as a colony.

You forgot that Lincoln imprisoned both the newspaper editors and members of the Maryland legislature.