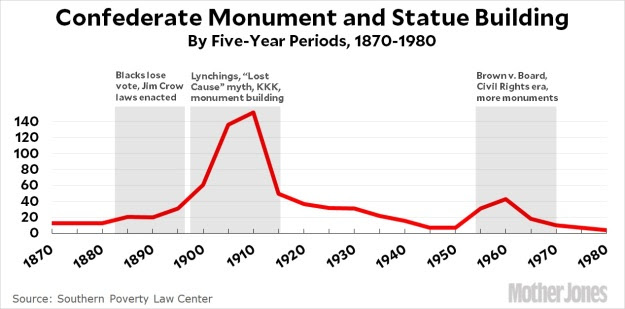

The diagram below graphs the number of Confederate statues erected between 1870 and 1980. Since the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) compiled the data, they suggest the memorials were most frequently put in place during periods of flagrant anti-black sentiment in the South. In short they imply that racism was the prime motive for Confederate monument-building. In truth, however, more compelling reasons are as obvious as cow patties on a snow bank to the thinking person.

The two most notable peaks were 1900-to-1915 and 1957-to-1965.

The SPLC implies that the first wave was due to “lynchings, ‘Lost Cause Mythology,’ and a resurgent KKK.” Facts, however, don’t support their conclusion. First, the KKK’s resurgence was in the 1920s, which was at least five-to-ten years after the first peak had already past. Moreover, the state with the most KKK members during the 1920s was Indiana, a Northern state. Second, the number of lynchings were steadily dropping during the 1900-to-1915 period. Third, “Lost Cause Mythology” was a strong influence until at least 1950 and by no means concentrated in the 1900-to-1915 period.

[Learn more about Civil War and Reconstruction at My Amazon Author Page]Contrary to the SPLC’s imaginings three factors were the chief cause of the first surge from 1900-to-1915. First, the old soldiers were dying and survivors wanted to honor their memories. A twenty-one year old who joined the Rebel army at the start of the war was sixty years old in 1900 and seventy-five in 1915 when life expectancies were shorter than today. Second, post-war impoverished Southerners generally did not have enough money to even begin erecting memorials to fallen Confederates until the turn of the century. The region did not even recover to its level of pre-war economic activity until 1900, which was thirty-five years after the war had ended.* Third, until at least 1890 the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was hostile to any display of Confederate iconography. The GAR was a Union veterans organization that held considerable political power until at least 1900. By 1893, for example, they so successfully lobbied for retirement benefits that their pensions totaled nearly 40% of the federal budget.** Annual disbursements for Union veterans pensions did not top out until 1921.

As for the second surge between 1957 and 1965, the SPLC predictably attributes it to Southern resentment over public school integration and the 1960s civil rights movement. Nonetheless, it was more likely due to initiatives that celebrated the Civil War Centennial.

*Ludwell Johnson, Division and Reunion, 190

**Jill Quadagno, The Transformation of Old Age Security, 45